The curious case of Qingdao, China's land value tax

What we can learn from a German colony's LVT experiment

In the late 1800’s, Germany secured a 99-year lease from China for the territory of Jiaozhou Bay (rendered as Kiautschou in 19th century German), with its administrative capital in the city of Qingdao (alternatively spelled Tsingtao). Germany exercised full sovereignty over this territory and immediately instituted an aggressive tax on the unimproved value of land. Land value tax was the chief tax in the jurisdiction, with other taxes minimized or nonexistent—at least at first. German rule over Qingdao abruptly ended with the outbreak of World War I, with the Empire of Japan eventually seizing the territory for itself.

The case of Qingdao’s Georgist regime is significant for several reasons: it had a straightforward and high LVT, it lasted long enough for its effects to become measurable and well documented, and other taxes were minimized.

The Qingdao experiment directly inspired Sun Yat-Sen, the Chinese statesmen revered by Nationalists and Communists alike, the man credited with overthrowing the Qing monarchy and establishing the first Republic of China. Wilhelm Matzat attributes the following quote to him:

I liked Tsingtao quite immensely. It is the model city for the future of China, and if just ten people from each of our 500 counties were to go to Tsingtao to study its administration, its urban and rural roads, its magnificent shipyard, its harbor, its university, its forestry facilities, and its municipal and government facilities, an infinite amount of good could be achieved for China.

I’m relying on a few key sources for this article:

Michael Silagi’s “Land Reform in Kiaochow, China: From 1898 to 1914 the Menace of Disastrous Land Speculation was Averted by Taxation”

Wilhelm Matzat’s “Neue Materialien zu den Aktivitäten des

Chinesenkommissars Wilhelm Schrameier in Tsingtau” (which directly reproduces several primary sources!). Text is in German.

Two articles by Matzat, both in Zeitschrift für Sozialökonomie, one is the March 1999 issue, the other the September 1992 issue. Both are in German.

Ludwig Wilhelm Schrameier’s Aus Kiautschous Verwaltung, 1914 — public domain, available on Internet Archive. Text is in German.

Dirk Loehr, Shihe Fu, and Li Zhou’s “The Qingdao Land Regime—Lessons Learned”

Why try Georgism?

The German colonialists who acquired the territory at the barrel of a gun didn’t institute Georgist polices out of the goodness of their hearts, but from self-interest—they wanted a well run colony, and prior German colonies in East-Africa were infamously wracked by private land speculation. Admiral von Diederichs, the first governor of the new territory, is quoted by Silagi as saying:

It was our firm conviction from the outset that land speculation with all its consequences, as we experienced them in other East-African coastal areas, had to be made impossible.

How then did Georgism of all things find its way into the admiral’s ears? Silagi suggests that Qingdao is an early example of what we would now call the “posting-to-policy pipeline,” where someone writes an well-timed article that goes on to directly influence key people in government. Otherwise obscure German land reformers apparently pulled off this exact trick with the German Navy, who wound up in charge of Qingdao. Here’s Silagi (emphases mine):

Frei Land was a periodical with an extremely limited circulation. It was completely ignored by anyone outside the tight circle of the organized land reformers. But, evidently, support even from this corner was welcome…the Colonial Office ordered several copies of that particular edition of Frei Land for distribution among the leading political circles in Berlin.

Thus the articles reached the Navy Department. There the arguments contained in these essays were taken up by a number of naval officers, foremost among them the officer who was later to become Grand Admiral-Alfred von Tirpitz, then Secretary of the Navy…subsequently, the Navy Department became a sort of stronghold of land reform ideas.

The chief architect and author of the actual policy was one Ludwig Willhelm Schrameier, who explained his principles thus:

To attract German capital and labor to barren lands fighting powerful foreign competitors. The chances for successful colonization primarily depend on cheap urban and rural lands. Now, all achievements by the municipal and imperial governments tend to increase real estate values; and as soon as land is utilized, individual greed raises its value in a way to depress living conditions and to decrease competitive capacity.

Hence, the most important goal of all colonization is to protect the soil, as indispensable for human endeavors as air and sun, from being abused or withheld selfishly, and at the same time not to impede individual enterprise.

I should note that there’s some scholarly debate about how much Henry George himself and Frei Land were conscious inspirations for Qingdao’s “Georgist” reforms, or whether the ideas were arrived at entirely independently by Diederichs, Schrameier and, co.

Silagi insists George and the German land reformers were a direct influence, but Matzat disputes this. Digging into the debate, Matzat makes a credible case. Wilhelm Matzat was actually born and raised in Qingdao, and was a direct descendant of the original German colonists. More importantly, he discovered and published long lost primary sources directly relevant to the debate, including Schrameier’s original manuscript draft for the colony’s tax policies. Matzat shows that not only does this early draft lack any reference to George, but also that alongside the “pro-Georgist” policies, the original version included a few “anti-Georgist” proposals such as taxes on trade which were later struck in the final implementation. Here’s Matzat:

[Schramaeier’s] original proposal was as follows:

1. Land sales,

2. Trade tax,

3. No income or rent tax, but rather a relatively high real estate tax.

The proposed trade tax is, of course, the surprising element of the discovered original draft. This, in turn, leads to the second surprise: in the final version, the trade tax is dropped, but with the remark that it might be levied later, only "when a certain trade has moved here."

Matzat’s thesis is that we’re looking at coincidental convergence rather than direct influence, and that Schrameier was pragmatically rather than ideologically motivated.

Frankly, I don’t really care whether Henry George himself gets any credit or not; the Qingdao case study fascinates me because it lets us investigate several open questions:

What would a maximalist Georgist regime look like in practice?

How accurate do land assessments have to be for LVT to work?

In what ways did Qingdao fall short of Georgist ideals?

Let’s tackle these one by one, starting with:

What would a maximalist Georgist regime actually look like?

As far as tax policy goes, there would be no (or nearly no) taxes on labor, capital, or trade. Instead, there would be a land value tax that captures all (or nearly all) of the annual rental value of land. That means no income tax, no sales tax, no tariffs, no capital gains tax, no wealth tax, only land value tax—which thereby becomes the “single tax.”

As we will see, Qingdao was not a pure single tax regime, but let’s go through the features of a hypothetical idealized Georgist regime anyways and see how close Qingdao gets.

1. Universal Building Exemption, high land tax

Pure Georgism exempts all buildings and improvements from taxation and levies a high annual holding cost on land. Here’s Silagi:

The core of this statute was a land tax assessed at 6 per cent per annum of the land value to be re-ascertained at regular intervals, deducting, of course, the value of all improvements made by the owner.

Matzat backs Silagi’s conclusion up, as does the statute itself—buildings were not taxed, and a 6% LVT was indeed a core feature throughout the colony’s lifetime.

“Six percent” is kind of an abstract figure in isolation. Is that a lot? What does it actually feel like to live under a six percent land value tax?

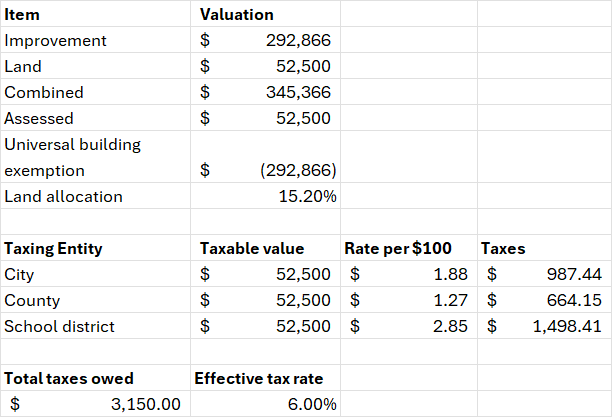

Let’s use my own property tax bill for my home in suburban Texas to find out. Here’s the valuation1 that my local central appraisal district sent me for 2024:

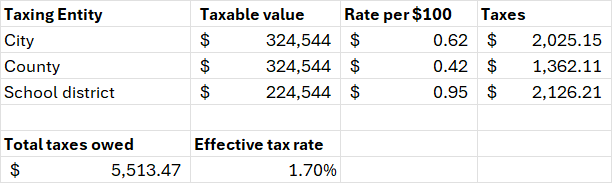

The “assessed” line is the actual taxable value of the home. Here’s what I actually owed in taxes that year:

I’m currently paying taxes on both the land and the building, and the effective tax rate on the combined values is 1.7%—pretty standard for Texas, but considered fairly high compared to the U.S. average. So if 1.7% is “high,” then jumping to 6.0% sounds like a huge leap—but let’s wait to see what happens when we exempt all the buildings first.

First, we need to swap out the wimpy homestead exemption for a Texas-sized universal building exemption. Then, we’ll change the tax rate to match Qingdao’s 6% LVT. How much will I wind up paying? Try to guess whether my taxes will go up or down before you scroll.

.

.

.

.

$5,513.47 - 3,150.00 = $2,363.47Even with a massive 6% LVT rate, I still save about two thousand bucks, as would other median Texas homeowners like me. What if my land is undervalued? Well, even if the land rises to be more like 25% of total value, I’d still save a few hundred dollars compared to what I’m paying now. And that’s just based on shifting property taxes around—recall that Qingdao had zero income tax.

Now, this isn’t a perfectly fair comparison—Qingdao was a small coastal colony from over a hundred years ago whereas Texas’ suburbs sprawl endlessly in all directions, and also Texas is part of the modern USA whose spending levels are astronomical.

My one and only point with this exercise is to give readers a concrete feeling about how different a “low” property tax rate and a “high” land value tax rate end up working in principle—it’s all about how much of the property’s value is due to the land alone. If you anchor on what a X% property tax “feels like,” you will wildly mis-interpret how an X% land value tax actually plays out.

Under a Qingdao-style LVT, property in low value areas that’s decently built up (like my house) will tend to save compared to a conventional Texas-style property tax, whereas property in extremely high value areas that’s underbuilt—such as the surface parking lots in the heart of my city’s downtown valued for millions of dollars—would see their taxes increase, encouraging those landowners to either develop the land commensurately or else sell it to someone who will. Incidentally, this is what our sources tell us happened in Qingdao.

2. No other taxes

Qingdao wasn’t a perfect single tax, because over time a few other taxes and duties started to creep in. Per Silagi:

It is true that after some time the Kiaochow administration abandoned its policy of complete freedom from customs duties, but except for a few minor levies and duties, including a dog licence, there was only a tax on land. It remained “the only significant tax aimed at the Europeans.” Thus, by and large, the Georgist program of a Single Tax on land values had become a reality in Kiaochow.

The “aimed at the Europeans” bit merits an asterisk, because the Qing Chinese crown, despite being forced to give up the territory to the Germans, still insisted on tariffs on goods that crossed the Chinese/German border. Tariffs are a tax, and an anti-Georgist tax at that, so this would serve to undermine the “single tax” narrative, especially when you consider that a portion of tariff revenues where shared with the German Qingdao government.

In the early years the only tariff levied by the Chinese customs office was on opium, arguably a Georgism-friendly Pigouvian tax, but after 1905 the Chinese tariffs expanded considerably and only goods that were merely passing through the port to other final destinations remained untaxed.

There were also two different “land taxes” in Qingdao that are often mixed up—a straightforward 6% LVT, as well as a “land increment tax,” a 33% capital gains tax on the increase in land value of a property, due on sale. The latter is certainly a policy with a similar aim as LVT—the capture of the “unearned increment” of land value, but it’s a departure from strict Henry George orthodoxy.

Nevertheless, Mazdat’s analysis of the primary sources finds that of the two, the land value tax was indeed the dominant source of revenue:

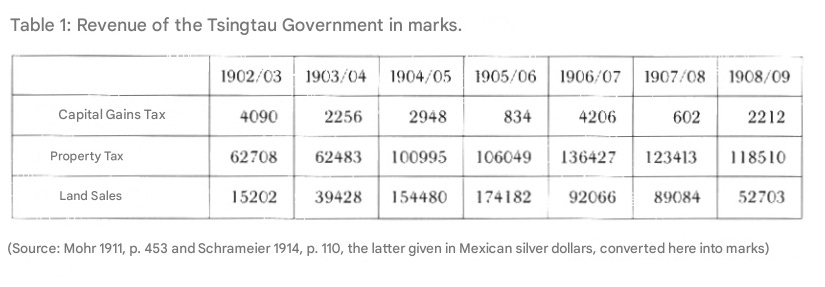

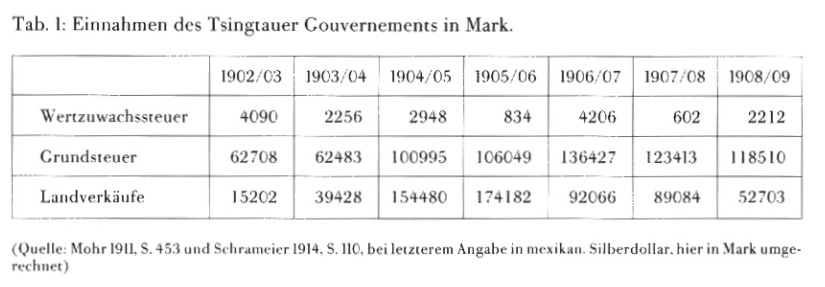

It was not the increase tax, but the land value tax along with land sales that constituted one of the most important sources of income in the first 10 years. I have compared these in a table for the years 1902-09 (Matzat 1992, p. 33). The revenue from the capital gains tax was minimal.

Here’s the Matzat 1992 source, by the way, and the table he’s talking about:

For those of you who don’t speak German, a quick Google Translate of that image yields the following:

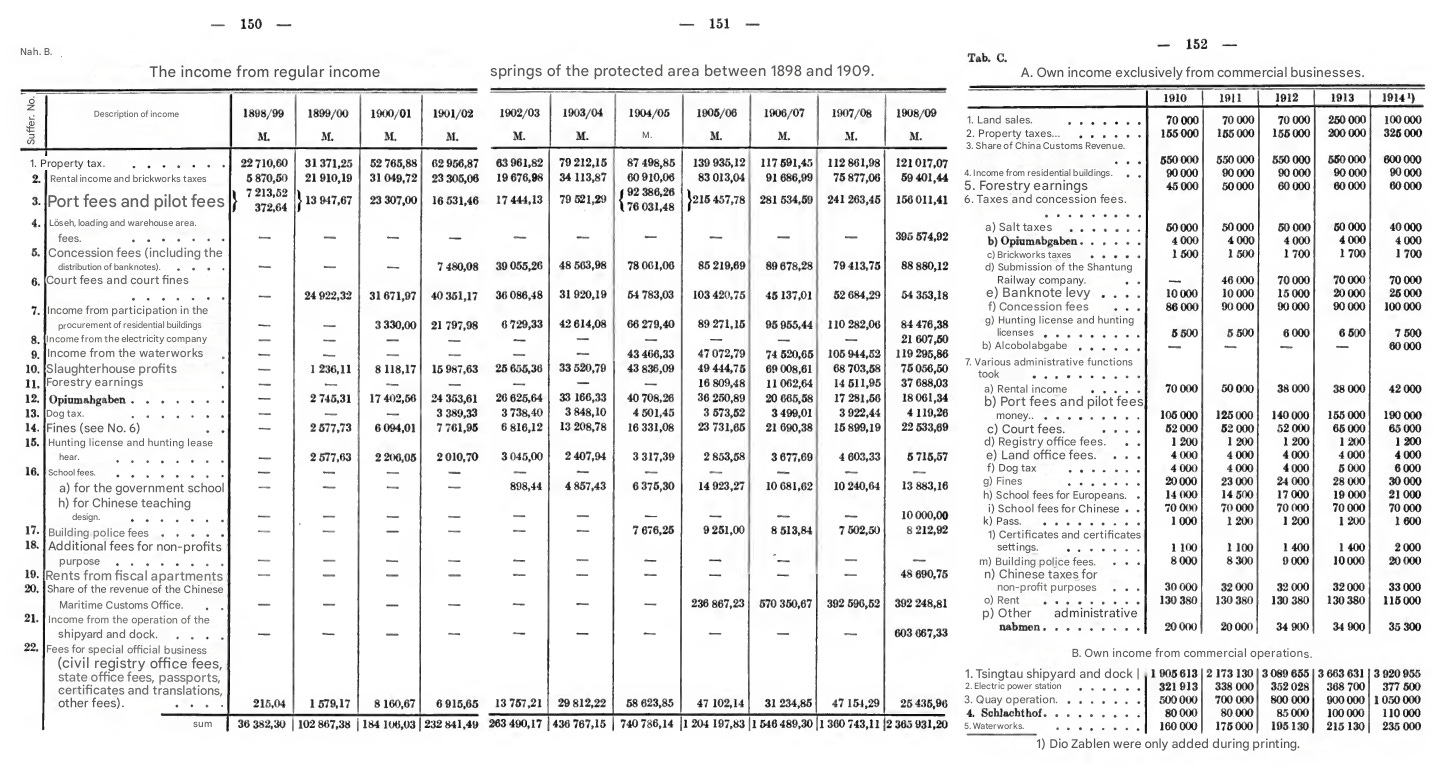

Now, even if Qingdao were to qualify as a “single tax” regime (which it doesn’t), that would not necessarily be the same thing as a “single revenue” regime. This is best illustrated with a table from Schramaeier’s 1914 book, Aus Kiautschous Verwaltung (automatically translated with google):

This chart shows that although the land value tax (translated as “property tax” above) was the chief source of revenue early on, this was later supplemented with various fees for government services, revenue from state-owned enterprises, and, starting in 1905, shares in the Chinese customs office tariffs, which quickly swelled to be the dominant income stream. Still, throughout the life of the colony there was no income tax or capital tax on the colony’s citizens.

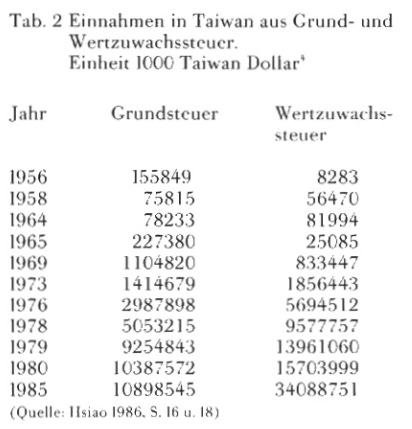

Interestingly enough, Mazdat asserts that the land policies of Taiwan were directly inspired by Qingdao, thanks to the influence of Sun Yat-Sen and his successor, Chiang Kai-Shek, who were both similarly inspired. Taiwan implemented a similar tax structure to Qingdao, but with a different weighting, choosing instead to emphasize the land value increment tax—the capital gains tax on land sales—and underweight the LVT through a self-assessment system which in Taiwan lacked teeth to combat under assessment. Here’s the table for Taiwan:

And here we have that in English:

I’ll have to save a full analysis of Taiwan’s situation for another day, but if you’re someone who speaks German and/or Chinese and wants to dig into all these sources, I think there’s a lot of valuable insights to find.

3. Full capture of the rental value of land

George’s ideals insist that one should capture all of the rental value of unimproved land. How close did Qingdao get to full rental capture of land value?

That depends on two things—the local capitalization rate at the time, and how close the assessed land values were to their true market value. The bottom line is that if land is assessed at full market value and taxed at a rate approaching the prevailing capitalization rate, you would expect full capture.

Modern cap rates tend to be around 5-10% in my corner of the USA, so a 6% annual tax rate on the selling price of land could approach full capture if we assume a low cap rate. According to the Rate of Return of Everything, historical cap rates in Germany bounced around 6-12% between 1870-1920. I don’t have a source for China, let alone Qingdao, but given that investment was riskier in a far east Asian colony, we should probably expect cap rates would have been higher than in Germany. This gives us a baseline expectation that the LVT was less than full capture.

Of course there’s an even easier way to tell if you’re capturing the full rental value of land or not—if land selling prices continue to rise even after the LVT, you’re capturing less than the full rental value. The land increment tax is a pretty good hint about this. Here’s Silagi:

The Land Statute also provided for an increment tax to be levied in case of transfer of property or at least every 25 years, if a parcel of land had not been sold within that period. This tax amounted to one-third of the increase in value of the "naked" land (Articles 6 and 7).

There would have been no need for an additional “increment” tax if the LVT alone was capturing the full rental value of the land, because land selling prices would not increase year over year if it was. Holding land prices down, rather than raising revenue, seems to have been Schramaier’s explicit intention for the land increment tax, as explained in Aus Kiautschous Verwaltung:

The increment tax maintains a place in Kiautschou land policy not as a fiscal measure, but merely as a preventative measure against harmful land speculation; its true purpose is achieved, according to a public statement from the time of its introduction, if it does not need to be levied at all. As predicted, revenues from this tax source have always remained low.

In this way the land increment tax was a sort of “safety valve” on what wound up being conservative land value assessments. If the LVT rate was too low, or the assessments didn’t hold steady with the market, the increment tax would catch it on the back end. The increment tax also served a secondary purpose as a big fat signal to speculators that land was not a reliable passive investment in Qingdao.

Given that there was still an observed rise in land prices and that the increment tax only captured 33% of the rise, I think we can safely conclude that even Qingdao’s very aggressive measures fell short of complete and total land value capture. It’s fascinating that such an aggressive land value tax was still “conservative” in this sense.

How accurate do land assessments have to be for Land Value Tax to work?

It seems that the procedure for land assessment in Qingdao was a bit crude by modern standards. For one, I found no evidence that the Germans had either heard of or employed the famous Somers System (if they had, Walter William Pollock would have likely bragged about it in his book).

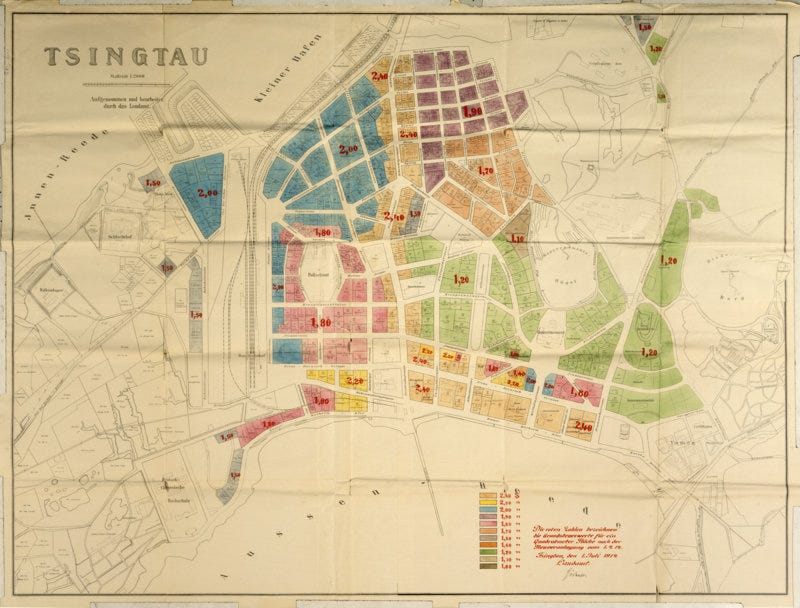

Instead, it seems that they relied on a few interlocking procedures to ensure that land obtained a fair assessed value upon which to levy the land value tax: mandatory transaction disclosure, ongoing and frequent assessments, right of state pre-emption, and public auctions.

Mandatory transaction disclosure:

Matzat 1999:

Before each resale of a property, the owner had to notify the government of his profit, stating the offered purchase price…To prevent evasion of the state's share of profits by stating a fictitious purchase price that was too low, the administration reserved a right of first refusal to purchase the property at the sale price offered by the owner.

Ongoing and frequent assessments:

Matzat 1999:

The purchaser of a parcel of land had to pay an annual land value tax (on the "bare" or unimproved) of 6%. The assessment basis for the first three years was the original purchase price, and later the reassessment, repeated at certain periods.

Right of state pre-emption:

The Germans gave themselves the right to buy any land they wanted from its original Chinese owners. They used this right at first only to buy a few key areas they needed for public administration. They used a rough assessment process to price pre-empted land at first. Loehr, Fu, and Zhou:

the land was roughly classified (first, second and third class). First class land was compulsory taken for 37.50 Mexican dollars per mu (75 Mark), second class land for 25.00 Mexican dollars per mu (50 Mark) and third class land for 12.50 Mexican dollars per mu (25 Mark).

Public auctions:

Other land was opened up to private ownership through auction, which would discover its market price directly. Loehr, Fu, and Zhou:

The administration only retained those areas, which should serve public purposes (public buildings, streets, forestation etc.). The remaining land should be transferred into private hands, by using auctions. At October 3, 1898, the first auctions took place (according to the blueprint of Hong Kong). The minimum prices were lower than the prices in other treaty ports, in order to make the migration to Qingdao attractive.

Quick note on “self-assessment”

If you squint at all the above, Qingdao also seems to have had something vaguely like a Harberger Tax in the mix. A classic Harberger Tax works by letting any individual set their own assessed value upon which taxes will be owed, but gives it teeth by allowing anyone else to buy it for that stated price. This differs from that, in that only the state had the right to call the bluff.

The bottom line

Put that all together, and it looks like the assessment regime in Qingdao was fairly rough-and-ready, and would likely fall short of the most stringent modern assessment standards.

That said, our sources indicate the colony was successful and developed nicely, so it’s a useful existence proof that a straightforward LVT could be pulled off even without computers and sophisticated mass appraisal software.

We should also consider that the surrounding policies might have served to buttress the basic LVT. For instance, the land value increment tax, despite the low revenue it brought in, provided a useful disclosure mechanism and incentive to report prices honestly, especially when paired with state pre-emption. The direct capture of increasing land values also arguably served as a valuable backstop mechanism should land become under-assessed.

In any case, it seems that the assessment scheme in Qingdao was “good enough”— market based, with incentives to disclose prices honestly, reassessed frequently, paired with supporting policies, and all accomplished with pen, paper, and slide rules.

YIMBY Qingdao?

As an aside, Qingdao had another statute not directly related to tax policy meant to spur development: the building order. This is best described not as mere YIMBYism but ultra-YIMBYism: landowners had not just a right to build, but a duty. Matzat 1999:

Before the auction, buyers had to submit a plan specifying the intended use, which had to be approved by the government. If the use plan was not implemented, the annual land value tax rose from 6% to 24%. If the plan was subsequently implemented, the tax fell back to its normal level. The development requirement was therefore intended to prevent the acquisition of land for purely speculative purposes.

How Qingdao fell short

Despite being a fascinating example of development economics, Qingdao fell short of Georgist ideals. We’ve already covered the fact that high tariffs crept in over time, but there were two other big ways in which it fell short: first, there was no democracy, and second, the natural resources, were captured and extracted on behalf of a foreign colonialist government, rather than Qingdao’s people. An excellent paper on the subject is George Steinmetz’s “Qingdao as a colony: From Apartheid to Civilizational Exchange.”

1. Autocracy is bad, actually

Nearly all political power was concentrated in the hands of the colonial governor. Initially there were two “representative” bodies, a citizen’s representative council elected by European property owners, and a Chinese committee whose members were initially chosen by local merchant guilds. These were later joined by a third body, a chamber of commerce, which had mixed Chinese and European participation.

Not only were these bodies exclusive and even racially tiered, but they had no formal power, and could only advise the governor. Although the local people enjoyed certain rights as citizens of the colony and allowed to live and trade as they pleased, Chinese citizens were citizens of the colony only and were not granted German citizenship.

Further, a two-tiered court system persisted, where Chinese were subject to both German law and Chinese law (as interpreted by Germans), whereas Germans were subject only to the former. An ideal government in Qingdao would have granted not just the franchise, but also equal treatment under the law, to all subjects, and without instituting an apartheid-like division based on race.

NOTE: Despite his general love for freedom and Democracy, Henry George himself had harsh views that singled out Chinese immigrants in particular, which is a place most modern Georgists part ways with their movement’s founder. In any case, in Qingdao it was the Europeans, not the Chinese, who were the immigrants.

2. Colonialism is bad, actually

We’ve previously covered Georgist policies towards natural resource wealth, in the case of Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, where e.g. Norway’s national resources are first and foremost understood to be the property of the Norwegian people. Despite Qingdao’s collection of land rents for the purposes of public benefit, the colony intentionally fell short of this same goal when it came to natural resources, because capturing, extracting, and exporting natural resources back to the mother country is kind of the entire point of colonialism.

Qingdao was “liberal” compared to Germany’s brutal African and Pacific colonies, but a truly Georgist government in Qingdao should have granted its people not only full enfranchised citizenship, but also shared Qingdao’s resource wealth amongst them.

That said, some colonial overlords are worse than others. When the Japanese empire conquered Qingdao and ended the German experiment, the treatment of the local Chinese population was unambiguously worsened, with large tax hikes, imposition of martial law, forced labor, and other deprivations.

The Bottom Line

From Aus Kiautschous Verwaltung:

This foresight has proven its worth. It cannot be denied that the colony, on the foundation once created, has developed beyond all expectations, and that the cheap land has attracted and continues to attract settlers, is undeniable.

When the Shanghai-based “East Asian Lloyd” is forced to admit that, when Shanghai was founded, a preparatory land policy, such as that implemented in Tsingtao, was neglected, and that this omission is taking its toll at every turn through the general increase in the cost of living and thus in the expenses with which every business in Shanghai must operate, this complaint about missed opportunities merely corresponds to the efforts that can recently be observed elsewhere in East Asia in adopting the Kiautschou system in new establishments.

Contemporary sources also bragged about the rich and swift development of the area, which soon sported schools, hospitals, and even a college for Chinese students, which explains the hearty endorsement of figures like Sun Yat-Sen.

What Qingdao has to teach us today

Qingdao is not the only time Georgism has ever been tried, but it is a particularly intriguing piece of evidence. It shows us that LVT can and has been effectively administered and that it yields exactly the theorized effects—it drives out speculation, checks rising land prices, boosts building, funds local public spending, and gives headroom to eliminate other burdensome taxes on labor, and investment. All this in turn yields to a general economic flourishing.

It also shows us that even crudely assessed land values can be adequate to power an LVT as long as they are “good enough” and refreshed continuously. We should still strive for as much accuracy and precision as possible, but if Qingdao’s administrators could pull this off more than a hundred years ago, we don’t need to wait for technological breakthroughs.

As for whether LVT can raise enough money to support a modern government, I think Qingdao is not the cleanest example. On the one hand, the sources claim that the LVT alone covered ongoing direct municipal expenses, but on the other hand the colony was a strategic naval base for a globe-spanning European empire; this necessitated ongoing military expenses and therefore subsidy from the German Reich. Fortunately, we already know about how much money LVT would be able to raise in a modern American context.

As for longevity, Qingdao shows us that “there’s no sovereignty like sovereignty”—their economic experiment was brought to a swift end when the territory was conquered by Japan. Applying that lesson to the modern context means that Georgist-friendly jurisdictions, be they municipalities, counties, charter cities, or devolved-power countries like Wales, should be wary of interference from above, and fiercely guard their rights to self-governance.

A toast to Qingdao

There is one final aspect to the legacy of the German colony of Qingdao that bears mention. A brewery was established there in 1903, which survived all the political transitions between the Japanese occupation, the subsequent civil war and subsequent cultural revolution, finally emerging on the modern stage as China’s second largest brewery.

The native Chinese residents have long since made the original German beer tradition their own over its century-plus history, and also maintained the old-style spelling for their beer’s brand name through the ages: Tsingtao.

So the next time you’re at your local supermarket, see if they have a case of Tsingtao in the imports section. Then grab a bottle and join me in a toast: to the future.

Lars Doucet is the author of Land is a Big Deal co-founder of the Center for Land Economics.

Incidentally, my home is worth much more now than when I first bought it—if I had to buy my home today I’m not sure I could afford it! Many such cases.

Great article. The real gem here is the 6% tax on assessed land values, and how that's both larger than my current city's budget and demonstrably not high enough to totally destroy the land values like LVT haters say will happen.

My city's budget (total spending, not revenue) comes out to 5.4% of assessed land values, and that's with the standard US undervaluing of land. Increasing our budget to 6% LVT would add $200 million to the city coffers, and fixing our assessments to stop undervaluing land would likely require lowering the LVT rate to avoid large tax hikes!

Enjoyed the article. And I intend to enjoy a Tsngtao or two in your honour.