Norway's Sovereign Wealth Fund

A Georgist Success Story

Meet Farouk Al-Kasim, a Norwegian-Iraqi petroleum geologist, Knight of the Royal Norwegian Order of Saint Olav, and the man widely credited with saving the Kingdom of Norway from the dreaded "resource curse" that had long haunted his birthplace of Iraq.

Al-Kasim is not generally referred to as a Georgist, and I would be surprised if he explicitly described himself as one. Nevertheless, the policies he helped establish with regards to the management of Norway's natural oil resources are right in line with Georgist thinking.

The Resource Curse

The resource curse is a phenomenon where a bounty of natural resources leads not to prosperity and wealth, but instead to stagnation, corruption, conflict, and even authoritarianism. According to the national resource governance institute:

Political scientists and economists argue that oil, mineral and gas wealth is distinct from other types of wealth because of its large upfront costs, long production timeline, site-specific nature, scale (sometimes referred to as large rents), price and production volatility, non-renewable nature, and the secrecy of the industry.

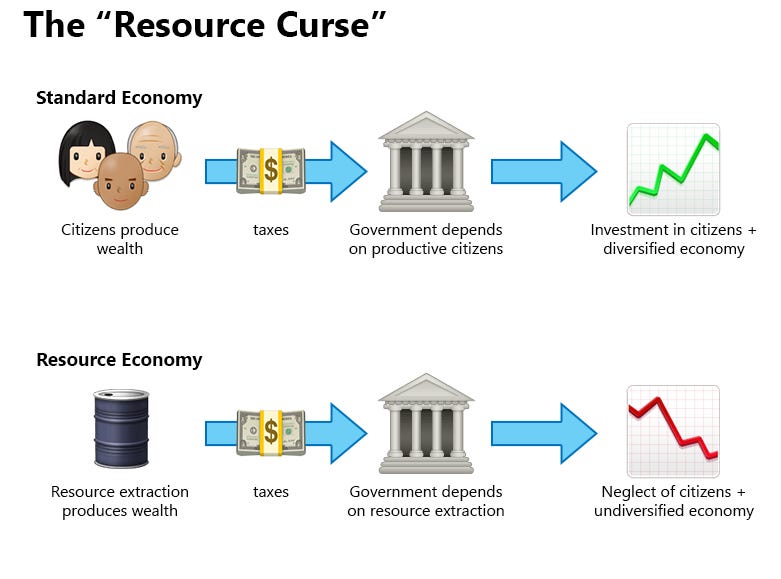

Because resource-rich governments get their money from extracting natural resources rather than the economy at large, they don't have as much incentive to build a well-developed and diversified economy in the first place.

When the productive power of the people themselves is no longer the source of the government's wealth it becomes easy to either ignore them entirely, or to exclude everyone except a favored in-group. A subset of the resource curse is called Dutch disease, where resource extraction can have negative effects on the rest of the economy:

The resource curse isn't unique to the Middle East and the Netherlands, many Americans have seen it up close over the centuries – it's commonly alleged that abundant coal deposits in Appalachia contribute to the region's persistent poverty. Likewise the Confederacy's over-dependence on slave cotton is commonly cited as the cause of the South's poor industrialization, which ultimately cost them the war.

Al-Kasim's Quest to save the Kingdom

Sir Farouk was born in Basra, Iraq, in 1934. At 16, he was selected by the Iraq Petroleum Company to study abroad in petroleum geology, after which he would be ensured a job. He studied in London, where he met his future wife Solfrid, a Norwegian woman. They married and later moved back to Iraq, where al-Kasim quickly rose through the ranks at the Iraq Petroleum Company. However, in 1968 they were forced to leave for Norway to seek medical treatment for their son's cerebral palsy. In Norway, the search for oil had been ongoing for five years with no success, so the young petroleum geologist was not optimistic about his career prospects.

He started working for the Norwegian Ministry of Industry and was asked to assess the results of some early oil exploration in the North Sea. Al-Kasim ran the numbers and quickly realized Norway was sitting on a motherlode of oil. Lisa Margonelli for Pacific Standard quotes Farouk:

“Norway didn’t know anything about oil,” he told me. But leaders knew about the resource curse; they knew they didn’t want a tsunami of fast money and corporate influence to wash over their neat country. “It scared them,” al Kasim said, and better than most, he could empathize. “I had lived the agonies of being a stooge of imperialism,” he said.

Lisa goes on to say that the Middle Eastern countries of the 50's and 60's looked to nationalization of oil companies as the way to escape imperialism, but this just caused other problems:

These new petrostates concentrated oil, money, and power in the hands of a few, creating the very definition of path dependency as their economies stagnated. “If you simply replace international oil company monopolies with state owned monopolies, it’s not an improvement,” al Kasim says.

Al-Kasim's solution was to craft a private-public arrangement that avoided both the Scylla of corporatist privatization and the Charybdis of state socialism. The problem with both is that monopolies drive out competition, and to Al-Kasim, "Competition is the essence of competence."

Al-Kasim and his colleagues put together a white paper that called for two things: the creation of Statoil, a state-owned oil company, and an independent regulatory body in the form of the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate. Both are still going strong to this day, though Statoil later changed its name to Equinor. Statoil, the NPD, and foreign oil companies would all work together, with the Norwegian people ultimately calling the shots:

By bringing in international partners, al Kasim’s idea avoided the state monopoly he’d seen in the Middle East. Statoil would develop local expertise and provide jobs for Norwegians. The Petroleum Directorate, then, would be a sort of referee, making sure that the oil projects served Norway’s interests by minimizing environmental impacts while maximizing jobs and profits for Norway.

The practical upshot of Farouk's plan was that Norway should massively subsidize oil exploration, while massively taxing its extraction.

If you've been wondering what the Georgist connection is, here it is - the tax on extraction amounted to a massive severance tax on Norway's oil deposits, a special kind of land value tax on a special kind of economic land. The message was, "This isn't your oil, Conoco-Phillips, it's the people's oil, and if you want to lay hands on it, you must compensate the people."

Everything for Norway

Norwegian Petroleum lays out the whole scheme, which is still in effect today. Oil companies' net profits are taxed at a staggering 78%. However:

The petroleum taxation system is intended to be neutral, so that an investment project that is profitable for an investor before tax is also profitable after tax. This ensures substantial revenues for Norwegian society and at the same time encourages companies to carry out all profitable projects.

At the same time, Norway allows you to deduct everything related to exploration and research and development, encouraging as much investment as possible:

In general, only the company's net profit is taxable. Exemptions, such as royalties, are no longer a part of the tax system. Deductions are allowed for all relevant costs, including costs associated with exploration, research and development, financing, operations and decommissioning.

There's also a whole bunch of provisions for dealing with the long-term nature of oil exploration and spreading risk over multiple sites on the Norwegian shelf, and lots of other little warts and hairs that have sprouted over the years to deal with specific edge cases. You can read all about it on the site.

So what are the effects of such a high tax rate, simultaneously paired with deductions and subsidies for exploration and R&D? According to FT, innovation:

Most of the oil found in the world is never recovered: the average extraction rate worldwide is around 25 per cent. Norway averages 45 per cent, and for that, Olsen gives al-Kasim much of the credit: he pushed the government to increase extraction rates; insisted that companies try new technologies, such as water injection in chalk reservoirs or horizontal drilling; and threatened to withdraw operating licences from companies that balked. “It is this culture, a culture of ‘squeezing the last drop out’, which he cultivated,” says Olsen.

But this wasn't just about making more money for Norway:

The extraction rates al-Kasim forced through significantly boosted oil and gas revenues – and so indirectly, the size of the savings fund. But the culture of pursuing the “last drop” brought greater benefits than just money pouring in. It spurred the development of technological expertise that has enabled Norwegian companies to compete with the best in the world.

The system is set up in such a way that companies are encouraged to spend as much as possible on tools, innovation, methods, training, and discovery. Norway won't tax you for that and will even reimburse you in many cases. But when you finally start pumping the oil, most of it goes to the Norwegian people (by going directly into the Government Pension Fund).

This flips the traditional investment narrative – instead of needing fat profit margins to justify huge risky investments, Norway will eat most of the risk for you in exchange for most of the profits. That's a pretty good deal, and history shows us plenty of companies took Norway up on the offer.

“Norway is the only country in the world where the state and the capitalistic entities work together as partners, and the co-operation works, really works,” says al-Kasim. Paradoxically, state involvement makes this easier. “To put it very simply, you put your wallet where your mouth is … When you take 50 per cent of the risk, and other companies take maybe 15 per cent tops, it is hard for them to say you’re crazy, right?”

The Norwegian severance tax on oil extraction has all of the predicted effects of an LVT – it encourages efficient use of the land: getting the most value out of a site, extracting as much resource as possible, and minimizing on-site pollution. It also makes sure that a resource nobody created is used for the benefit of everyone, not just the first person to squat on it. And speaking of squatting, it prevents speculators from grabbing oil wells and holding them out of use, which instead of encouraging the most efficient use of a small number of sites, encourages the inefficient use of an ever-expanding number of sites. This waste and over-exploration greatly increases environmental damage.

This is no minor concern for anyone who remembers BP's Deepwater Horizon debacle. And it's not a problem endemic to British Capitalists, because Mexico's state-owned oil company Pemex recently set the ocean on fire with the Ku-Maloob-Zaap disaster.

But even if we could drill safely and efficiently everywhere with zero direct environmental impact on the oceans, we still need to talk about the fact that hyper-green countries like Norway are still selling this stuff so people can burn it.

Climate Change

Okay, so Norway found a clever way to keep both rapacious foreign companies as well as aloof domestic elites from monopolizing the people's oil and privatizing the benefits. Norway even figured out how to do it in a clean and efficient way.

But Climate change isn't getting any better, so do we really want to encourage people to drill for oil at all? Isn't this a big problem?

It is a big problem, and I totally agree!

The issue with severance taxes on fossil fuels is that even if you can use Al-Kasim's "Norwegian Model" to dodge the resource curse, you're still making a lot of profits from activities that ultimately damage the environment. Even though 98% of Norway's domestic energy production comes from renewable sources and the country boasts the largest number of Tesla cars per capita, it's still the world's 14th largest Oil exporter, and the 5th largest per capita. So can we really say this was a good thing? Some argue that we should have just left all the oil in the ground.

I think we need to be realistic and consider what likely would have happened without the Norwegian Model. From the FT article (emphases mine):

The government has an ambitious aid programme (now called “Oil for Development”) to help poor, oil-rich states manage their natural resources. The official pointed out the irony in this, given that “it was an Iraqi guy who helped us set everything up in the first place. Without him we would just have let the American oil companies decide how to do things.”

I think the best argument here is that if you're going to do something that has negative consequences, you should do it in the least worst way.

In America we are still grappling with the legacy of companies that extract resources, keep the profits for themselves while violently oppressing those who oppose them, and then leave the community to clean up the mess. The coal gets burned up anyways, but the people were impoverished, the land was destroyed, and the money went to enriching private companies who just kept doing the same thing over and over again.

At least in the case of Norway every penny of Oil tax has gone into a fund that can be used to invest in a cleaner future. Just as importantly, the money, jobs and economic boost spurred education and economic development.

For historical context, my mother grew up on a farm working in the fields with hand tools, with no electricity, no indoor plumbing, living in a remote village accessible only by boat. That was in the 1950's, and she came from a relatively well-to-do landowning family. Careful stewardship of natural resources (including but not limited to Oil) put toward the public good helped make modern Norway's highly educated, diversified economy and enviable standard of living possible.

None of this erases the fact that all of that oil was burned and contributed to climate change, and is still flowing today, and "the Americans would have done the same thing, but in a less progressive way" isn't an absolution.

Georgist land and resource policy is basically a way of saying: if you wish to take the bounties of nature for your own private use, you must compensate the people for what you take. When it comes to land, your occupation of a plot means the exclusion of everyone else, so you must pay land value tax. When it comes to resources, you taking them out of the ground means they are lost to the next generation, so you must pay severance tax. When it comes to pollution, you have degraded the Earth itself and imposed a cost on everyone, so you must pay pigouvian taxes.

The most popular Pigouvian tax is the carbon tax. Burning fossil fuels comes with a cost – climate change, air pollution, cancer, ocean acidification, etc. The people who impose that cost on others are the ones who must pay for it. This is the last missing piece of the puzzle.

A Model for Success

Norway’s model for oil wealth is an excellent example of Georgism in action. Sir Al-Kasim was probably entirely unfamiliar with Georgist ideas, but his system is founded on identical principles. Oil is a kind of economic land- naturally occurring, and of fixed supply. Accordingly, it generates natural resource rents. The key to Norway’s success in oil exploitation has been the special regime of ownership rights which apply to extraction: the severance tax takes most of those rents, meaning that the people of Norway are the primary beneficiaries of the country’s petroleum wealth. Instead of privatizing the resource rents provided by access to oil, companies make their returns off of the extraction and transportation of the oil, incentivizing them to develop the most efficient technologies and processes rather than simply collecting the resource rents. Exploration and development is subsidized by the Norwegian government in order to maximize the amount of resource rents that can be taxed by the state, while also promoting a highly competitive environment free of the corruption and stagnation that afflicts state-controlled oil companies.

Georgism also offers the solution to the problems of pollution caused by resource consumption. The environment is the common property of man, and it is too often abused for personal profit. Georgist principles require payment for this use of public property in the form of the pigouvian tax, which has the double benefit of disincentivizing pollution and environmental degradation and forming a fund with which to mitigate the damages, restore the environment, and compensate those affected by it.

This has just been a brief sketch of one real-life application of Georgist principles. But as you can see, Georgism is much more than just a land value tax. Countries that follow the example of Norway in putting these principles into practice will doubtless find it an invaluable tool for improving the lives of their citizens.

If you would like to read more about al-Kasim’s work, I highly recommend his book, Managing petroleum resources : the “Norwegian model” in a broad perspective, which can be downloaded as an ebook for free, which covers the subject in exhaustive detail.

Furthermore, for a longer and more in-depth treatment of on Norway’s natural resource management and its Georgist roots, see this article I translated: Norway, the Once and Future Georgist Kingdom.

"The petroleum taxation system is intended to be neutral, so that an investment project that is profitable for an investor before tax is also profitable after tax. "

Do you know the specifics of how this is implemented?

Just being profitable (i.e. >$0 profit) wouldn't be sufficient because companies tend to analyse investments in terms of payback period (or maybe IRR).

Does Norway give subsidies up front so that the payback period is the same? If the investment profile is still the same for investors then how does the government make any money through tax? The statement seems to imply that the government keeps the investment profile the same, but that would seem to contradict that taxes are being charged. If taxes balance out the subsidy then how would Norway make money?

Thanks

This seems like a great model to apply to patent law, especially where government has enough of an interest in discovery that it will spend money to aid in R&D, especially in medicine. If there was research to find a cure for pancreatic cancer, for example, the government could heavily subsidize R&D efforts and then take a large portion of the profits when a cure is discovered and sold on the market.

Although I'm not sure if there's a way that system could make it affordable to the end user... perhaps a "sovereign health fund" that pays for the healthcare of the countries citizens