“Ten jobs for every nine men, then no man will coerce labor because labor cannot then be coerced.”

- Louis Freeland Post

In obscure years before the Great War, two paradigms collided. Socialism versus the Single Tax set the trajectory of the twentieth century - enterprise, invention and productivity struck by depression, revolution and war. The collision destroyed knowledge, fatally skewing our understanding of the boom-bust, of unemployment and economic inequality. A conceptual black hole now occupies the point of contact. Yet from it one paradigm birthed, painting itself across history, while the other… was obliterated.

Fragments of the collision can be found: for instance, in Chicago a few days before Christmas 1903, a fractious, rowdy audience of two thousand heard six speakers debate the resolution “That it is to the interest of the working class to take up the propaganda of Socialism rather than that of the Single Tax". The transcript was published as a book. The extracts below are something quite rare - a stenographic record, including audience participation, featuring experts in the medium of the day - public debate. Through it, might we somehow re-enter the gestalt of this deleted debate, grasp its deleted concepts? And having achieved that might we observe the prevailing paradigm (and perhaps everything else) through a different lens? Does it unmask redacted dimensions of today's equity debate? Does it in fact overturn that debate? Will we see the relationship between fundamental categories - nature, labour, capital, state - differently?

And also, can we sense from that record, in the air in the hall that day, an uncanny menace, an ill-will- a Cain measuring, and measured by, an Abel?

In 1903 'systemic economic inequality' was known as ‘the labor question’ or ‘the industrial problem’. It was the question Great Britain faced when sixty percent of recruits were found to be too malnourished for military service. And was it perhaps also the question America faced when President McKinley was assassinated in 1901? The shooter, child labourer, then steelworker, had lost his job in the 'Panic of 1893'. He became an anarchist, and said he shot the President "because he was the enemy of the good people - the good working people."

In thirty years the American working class had become as poor as the British working class. The Panic of 1893 was one of a succession of crashes punctuating the 'Long Depression' of 1873-1896. Unemployment, mass protests, boycotts, strikes, riots and their suppression spread nationwide. A great Janus-faced paradox had arisen – The Long Depression from one point of view was The Gilded Age from another: wealth generation had reached historic peaks, vast new production was everywhere to be seen, but not in the slums of New York and Chicago, which were no different to the slums of London and Glasgow. Many were compelled to ask – what mechanism drives wages to subsistence levels even in the most successful economies?

The labour question is the central focus of both paradigms: Socialism and the Single Tax actually begin in agreement: Labour does not receive its full wage and the reason for this is systemic. Both agree that wages are driven down by markets, by workers competing with other workers for too few jobs. For socialists the problem is the market system, is competition itself, for competition is nothing other than a Darwinian struggle for supremacy.

“Competition is the completest expression of the battle of all against all which rules in modern civil society. This battle, a battle for life, for existence, for everything, in case of need a battle of life and death ...”

- Friedrich Engels

Thus as the remedy, the Socialist program would abolish markets, abolish competition. The State would allocate resources and guarantee jobs.

The Single Tax paradigm, on the other hand, identifies an absence of competition as the root problem. Monopoly, the pure form of non-competition, and specifically land monopoly is the underlying cause of labour's underpayment. Without land there is no production. The abolition of all taxes on production (i.e. all taxes) it is claimed, would permanently raise demand for workers, ending unemployment. Labour would acquire market power, and ‘industrial slavery’, as Henry George, the leader of the single tax movement called it, would end. The the answer to the labour question is thus found within the market, an explicitly freer market.

“Abolish monopoly everywhere, put all men on an equal footing and then trust to freedom. In that way we would have the most delicate system of co-operation that can possibly be devised by the wit of man. The fight of labour is not against capital; it is against monopoly.”

- Henry George

Schism between the two movements began in the 1880s. At that time socialism was known through events such as the Paris Commune, 1871 and the 1848 revolutions in Europe before that. Failed revolutionaries from Germany and elsewhere resettled in America and activated once more. The single tax movement, on the other hand, had evolved from the land reform movement (which runs like a thread through all of the liberal reform movements of the Nineteenth Century). It stood alongside but distinct from campaigns ranging from rent reform to land nationalisation.

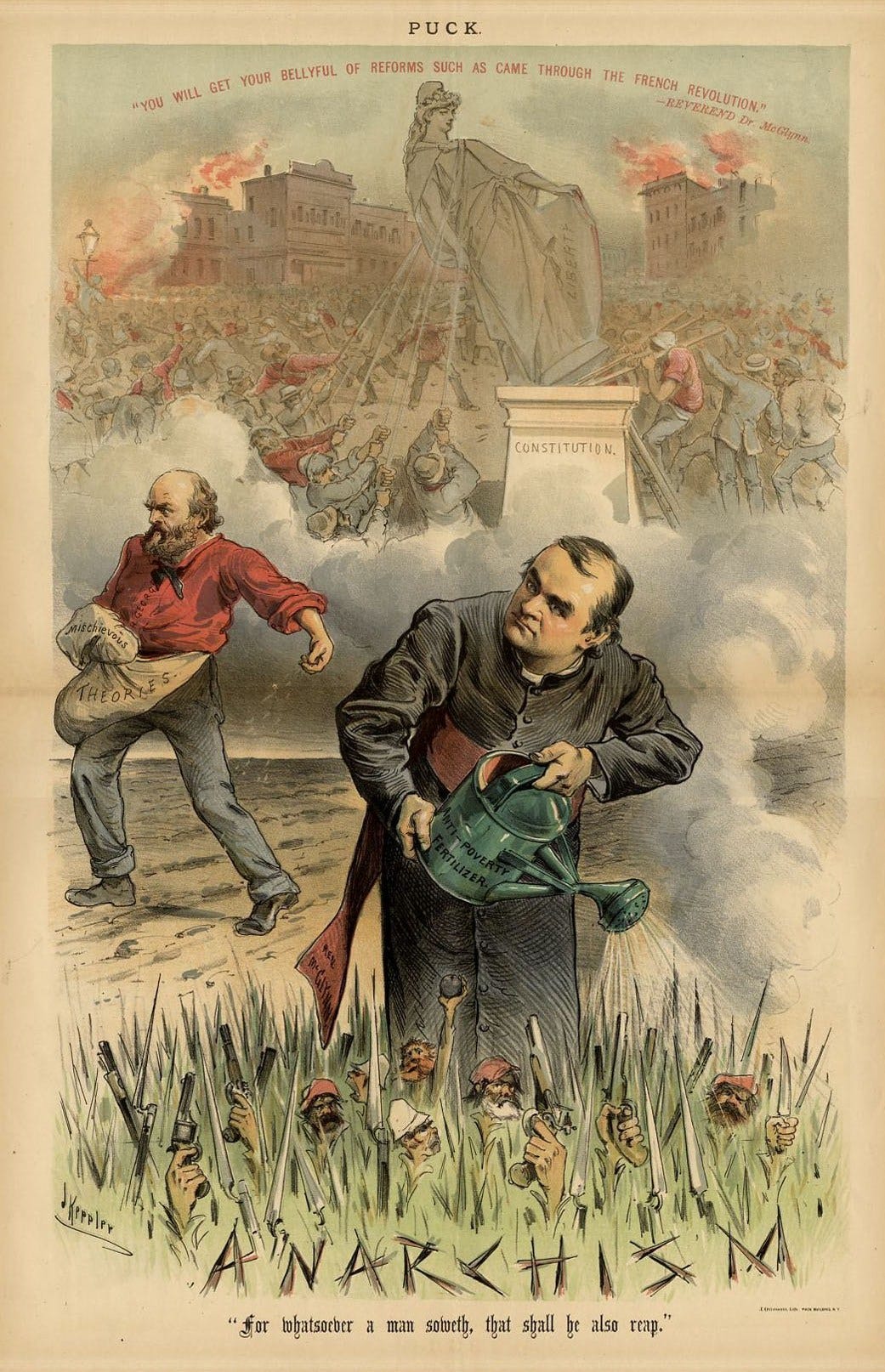

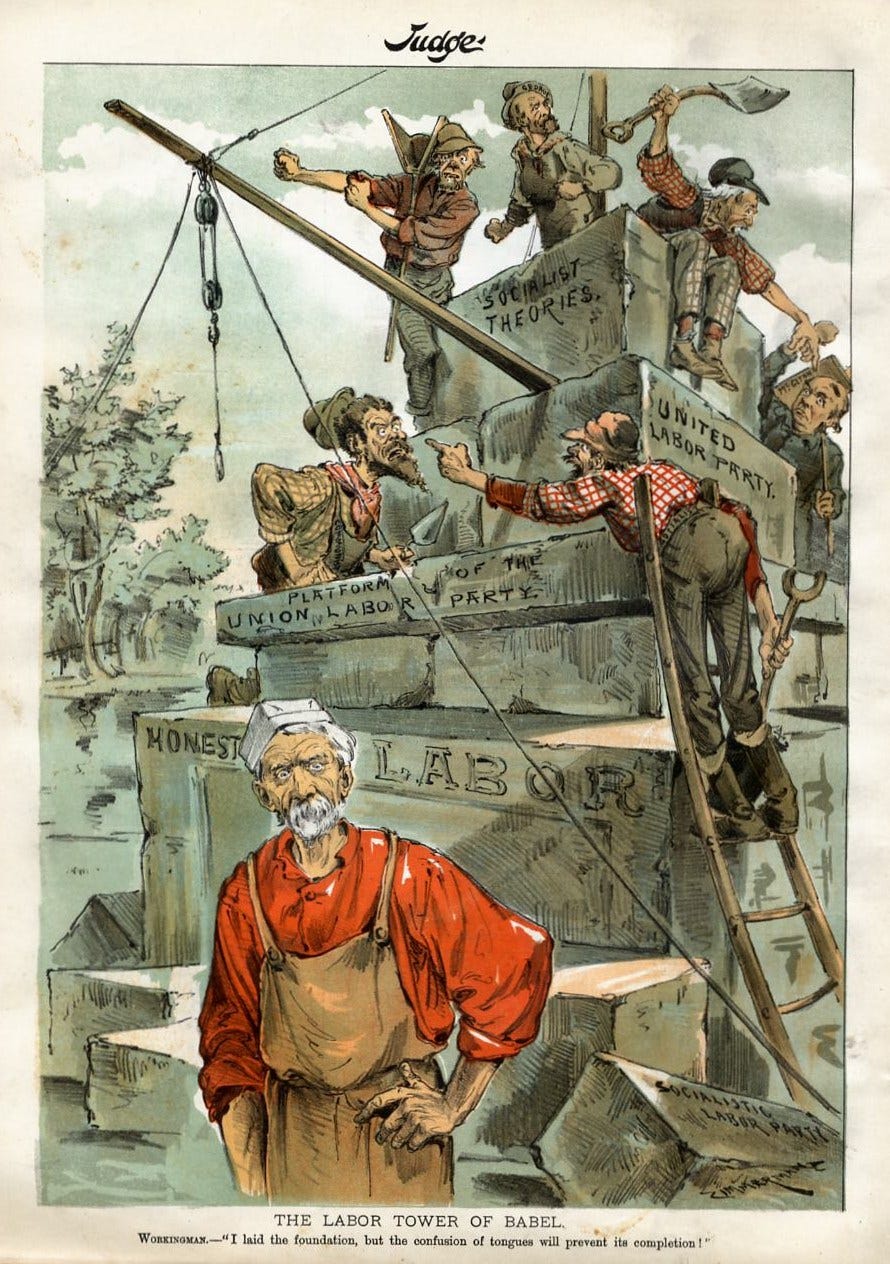

Both movements (Socialism and the Single Tax) were consistently vilified in the mainstream, equated with anarchy, revolution and terror. These conflations blurred the two paradigms into one; nevertheless when Henry George published his analysis of the labor question, Progress and Poverty (1879), he catalysed a debate that exposed their very real differences, and it ultimately drove socialism and the single tax apart.

The expansion of the franchise to the working classes accelerated the debate. There were votes to win. In the Great Britain, the Third Reform Act of 1884 had almost doubled the voting base, now including millions of landless agricultural workers. Some of them formed political movements, two of the most well-known were the Irish and Scottish Land Leagues, both influenced by George. Indeed it was in the British Isles that the Philadelphian first became famous, making five tours there in the 1880s and 90s, speaking and debating from London to Skye, crossing swords with dukes and academics, courted by figures from the political elite. For a period, Henry George’s ideas caught the zeitgeist, and many were impelled to react.

Socialist opinion was divided: non revolutionary Fabians owed much to George’s stirring up of activist energy and they took his thought seriously. Socialist William Morris, the famous fabric designer, called him

“Our friend and noble fellow worker [who] rising from among the workers, throws the glamour of his own sincerity over the most callous, and forces them to look into the misery around them.”1

Likewise, George Bernard Shaw was for a time one of the ‘really knowing’ socialists who esteemed George’s work, going so far as to declare that the Georgist solution (the single tax) would, if applied in full, achieve socialist aims.

“By his popularization of the Ricardian law of rent, which is the economic keystone of Socialism, and concerning which the published portion of Marx’s work leaves his followers wholly in the dark, Mr. George is doing incalculable service in promoting a scientific comprehension of the social problem in England.

Really knowing Social-Democrats would let George alone [because] the taxation of rent, the amount it went beyond replacing existing taxation, would produce Social-Democratic organization of labor, whether its proposers foresaw or favoured that result or not.”2

- George Bernard Shaw

Others were not convinced - “the choice has to be made between out and out Socialism and mere tinkering with taxation”. They agreed, or would come to agree, with the revolutionaries, who feared and shunned George. His fame, and his ‘superficial cure-all’ that only targeted ‘landlords’, might attract the support of capitalists and forestall revolution. In 1885 far left factions began heckling George on his UK tours. The following year George published Protectionism or Free-Trade, a declaredly liberal work, containing a critique of socialism, finding it unbalanced and counterproductive. But George never rejected - could never reject - the concept of the social realm contained within the notion of socialism. He believed in both individualism and socialism, a synthesis that is the very heart of his work:

“Individualism and socialism are in truth not antagonistic but correlative. Where the domain of the one principle ends that of the other begins.”3

- Henry George

But this could never suffice for unquestionably, Henry George supported free market capitalism, not in spite of but as a solution to the labor problem. For many socialists there could be no return. When, only weeks after splitting with the socialists in his movement, George spoke against the actions of the Chicago anarchists, sentenced to death for the Haymarket labour protest bomb attack, it all came to a head, in an unstoppered backlash. William Morris, whose praise had once been so warm, released his scorn:

“Henry George approves of this murder; do not let anybody waste many words to qualify this wretch's conduct. One word will include all the rest - TRAITOR!!”4

- William Morris

Schism became enmity became mockery. A left wing paper reviewing one of his speeches:

“The amount of flimsy, albeit dramatic, rhetorical effervescence which he unburdened himself of, in place of arguments, to support his patent quack poverty cure, exceeded anything his fiercest opponents could have attributed to this versatile Yankee.

To those who had known or heard him in the earliest days before he had deserted the people and become a party politician and stump orator for Radical capitalists, the man's present moral and intellectual degeneracy is pitiable to behold.”5

George faced enemies on both left and right. But what of the centre, the classical liberal centre from which the single tax sprang? The Liberal party in the UK was a force to be reckoned with - it had been the main party of government for the past half century - and extraordinary things were happening to it: strong factions began to follow the single tax paradigm, the land paradigm, to the root of poverty. In 1886, when the Liberals split over Irish home rule, it was ultimately a split over the land question - who should own the wealth generated on Irish land? 'Landlordism' - extortionate rack renting - figures such as J.S. Mill argued, had locked Ireland into a permanent state of near and actual famine. The Irish Land War of 1879-82, waged under the banner ‘No Rent’, attests to this. Through his writing and speaking George successfully made the Irish question - which was international news - a live case study in the single tax thesis. Clearly he played a part in the fracture and evolution of the Liberal party. He was the intellectual origin of key elements of Joseph Chamberlain’s Radical Program of 1885 and of the Newcastle program of 1891 which advocated for the taxation of land values. Although the split did damage the party - most of the next twenty years were spent in opposition - its comeback in 1906, bearing the single tax, was a landslide for classical liberal radicalism.

In the United States, parallels can be drawn: Theodore Roosevelt maintained a respectful stance towards George, he had run against him for mayor of New York in 1886, and lost. He certainly took land-centred economics seriously. On becoming president, he immediately nationalised millions of acres for parks and nature reserves, and he later wrote in favour of land value taxation. Moreover, his approach to the labor question famously focussed on monopoly, a key word of the single tax paradigm, a key word of the age. The Progressive era, generally said to begin in 1890, really began in the 1880s when Henry George re-cast land reform into voteable, progressive policy, and put it into mainstream politics in the world’s coming city. Everybody had taken notice.

“… no one could then foresee that in such a short time the movement would burst out with such irresistible force, would spread with the rapidity of a prairie-fire, would shake American society to its very foundations.”6

- Frederick Engels

1887: Henry George was at the head of the American labor movement, and the single tax was international news. U.S. socialists sought alliance. George’s party was a very broad tent, the politics of the emerging worker’s movement were still forming, and the socialists were welcomed into the mix. George hoped to win them over, and the principle that land value rightfully belongs to the community was his bridge.

“I have always refrained from accentuating any differences with socialists until forced to, regarding them as workers in the great cause of the emancipation of labor who, however superficial their views, illogical their theories or impracticable their plans, aimed at noble ends, and had laid hold of an important truth.”7

- Henry George

And then, at the height of its success, George ejected the socialists from his party. They were stunned. Some called it an excommunication – had he been influenced by the Irish American Catholic faction, which disdained socialism? Maybe, but George insisted that it was a party issue – the socialists, he claimed, had become a ‘party within a party’. He was careful to frame the issue as a split with a particular creed of socialism - the small cadre he expelled were European-exiled Marxist activists or ‘German socialists’, as they were called.

“The term ‘socialism’ is used so loosely that it is hard to attach to it a definite meaning. I myself am classed as a socialist by those who denounce socialism, while those who profess themselves socialists declare me not to be one.”8

- Henry George

New York’s Rev. Edward McGlynn, one of George’s closest friends, a mighty co-campaigner, (both are featured in the the cartoons left and below) was less conciliatory, speaking passionately against socialism in favour of “that magnificent individualism which was a generation ago and more the chief glory of America”.

“We want no foreign socialism. (Immense applause and cheers, lasting about a minute.) We want more of American individualism! (Great cheering.)

And if we demand that certain things shall be common it is because they either have been made common by nature, or because they necessarily become monopolies, existing only by the concession of the community, and therefore, they should exist only for the benefit of the community (Cries of “hear! Hear!” and applause.)”9

- Rev. Edward McGlynn

George was the next speaker:

“I most cordially reiterate what Dr. McGlynn has said. (Applause.) What we have banded ourselves together for is to carry out to its full extent the great principles of liberty enunciated in the Declaration of Independence. (Applause.)

For my part I hold that we are in this neither altogether socialistic nor altogether individualistic; that there is a true and proper line at which both principles unite and fall into their proper place (applause), and, as Dr. McGlynn has said, the line is that at which any business or function becomes a monopoly.”10

- Henry George

Ultimately, Single Taxers approach socialism as a form of Statism – the ideology of big government and centralised control. Statism is monopoly, the monopoly of coercion that libertarians speak of, but also of land, the root monopoly, in fact the very origin of the State.

“[Socialists] say the nation ought to abolish competition. Why you could not abolish competition without subjecting man to the worst form of tyranny – (Hear, hear and “No, no”) – and without stopping all progress. It is where competition is not permitted that there is stagnation.”11

- Henry George

Single Taxers view the American revolution as the nation's foundational rejection of monopoly state power. The single tax would shrink the bureaucracy, it favours localism over big government. As the debate below shows, recognition of the significance of state power, distinct from labour and capital, is a key dividing line between the paradigms.

After the 1887 split, Socialism crystallised as anti-Georgist. In Britain, the Labour Party, formed in 1900 and lead by the single taxer Keir Hardie, did not adopt the policy. Eugene V. Debs, who founded the Socialist Party of America in 1901, abandoned his former belief that capital and labor were ‘friends’ – a Georgist truism – after reading Das Kapital in prison. He had been jailed for leading the great railway strike of 1894, his American Railway Union had been crushed. Those events live in the background of the debate below for they centred on Chicago; indeed, one of the speakers, Seymour Stedman, witnessed the violent suppression of ‘Debs’ rebellion’, there and then converting from Georgism to Marxism.

“THE CONDITION OF THE WORKING MAN AT PULLMAN”

Incidentally, the affair, also known as the ‘Pullman strike’ is a case study in the debate at hand. Pullman, a railway car manufacturer, cut workers’ pay as a result of falling orders. But the firm also happened to be its workers’ landlord, and when it declined to lower rents it sparked a general strike. The question was never more starkly illustrated – who was the exploiter – Pullman the Capitalist or Pullman the Landlord?

“The increased production of wealth goes ultimately to the owners of land in increased rent.”

- Henry George

Debs was also influenced by Laurence Gronlund, author of The Cooperative Commonwealth, a popular, americanised interpretation of Kapital. He had been involved in the 1887 split. He said at the time:

“The German socialists who voted with the United Labor Party disavow any purpose to split that party. They want to convert it to State Socialism. It is not the breaking up of the party that we contemplate, but its perfection.

Henry George, upon whose theories the party’s principles are laid down, advocates the nationalisation of land. This we favour, but we go further and demand the nationalisation of capital also, and the abolition of all monopoly. Our ideal is a country where everything shall be centralised in the State.”12

This backs up George's claim that the socialist faction had sought to change the party platform. The ideal of a state super monopoly is a long way from George's correlative vision of the socialist principle as guarantor of individualism. (Note also, George did not propose land nationalisation.)

“With [the Socialists] the State is all and the individual sunk in the whole: with me the individual is the unit for the protection of which the State exists.”

– Henry George

It is now clear that on multiple axes – capital versus land, monopoly versus free markets, statism versus individualism, capitalism versus landlordism, wages versus rent, old Europe versus new America – Socialism and the Single Tax are radically different paradigms. The split of 1887 was inevitable, Henry George was simply the first to declare it.

By the time of the debate, the Socialist party of America was in full campaign mode - evidenced by the heightened rhetoric recorded below - gaining votes, which would peak at 6% in the 1912 presidential election. By contrast, following the death of Henry George in 1897, the American Single Tax movement had no national party and lacked the influence it emphatically had in British politics. The grass roots movement was extensive, the single tax was an established political brand, but it had delivered very little legislation. In 1895 for example, an attempt to convert Delaware to the single tax failed completely. It had been the largest campaign yet waged but the opposition deployed unwavering zeal. Later, an attempt by Populists and Georgists within Congress to give a land rent basis to the new Income tax was quickly reversed, setting the tax on an anti-worker, anti-entrepreneur trajectory. Setbacks for sure. Nevertheless, single taxers such as Thomas Shearman (author of Natural Taxation, 1897) and Max Hirsch (Democracy Vs Socialism, 1901) were re-sculpting the program to emphasise its practicality, the relative painlessness of its revolution, its modernity so to speak. Other campaigns, particularly in the west, would follow.

December 1903: Kitty Hawk, North Carolina - the Wright brothers, self-taught inventor-entrepreneurs with access to capital and land, invented a brand new paradigm for the century. It was not the first - a few months earlier, another inventor-entrepreneur, Henry Ford, formed a mass manufacture motor company in Detriot. And not far away in Macomb, activist Elizabeth Magie was patenting a new board game, designed to demonstrate the single tax paradigm: monopoly, we all learn, always wins Monopoly.

And in Chicago they debated Socialism versus The Single Tax, a power paradigm versus a technical paradigm. One lives, the other is … gone. The debate is dead. Is there any reason to hear those voices again, from the years before we disremembered?

Part 2 will feature a selection from the historical debate between the original Single Taxers and their socialist counterparts.

Originally published in The Single Tax Gestalt

Uneasy Alliance: The Reception of Henry George by British Socialists in the Eighties, Elwood P. Lawrence (1951)

Henry George and the Social Democrats, London Star, June 7, 1889

Protection or Free Trade (1886)

Commonweal, Nov 1887

‘Henry George in Manchester’, Commonweal, June 1 1889. Quoted from Uneasy Alliance: The Reception of Henry George by British Socialists in the Eighties (1951)

Preface to The Condition of the Working Class in England, London, 1887

Quoted in Socialism vs. Tax Reform: An Answer to Henry George, Laurence Gronlund, 1887

Protection and Free Trade, 1886

Speaking at the fifteenth public meeting of the Anti-poverty Society, New York, 1887

Speaking at the same meeting, New York, 1887

In debate St. James Hall, London, July 1889. From Henry George and H.M. Hyndman / The Single Tax versus Social Democracy

Socialists to the Front: An Interview with Laurence Gronlund, New York Sun, 1887

Great post. It's eerily remarkable how similar the debates they were having are with the debates we have now.

Then, as now, Henry George's ideas bridged the ideological divides. But ultimately, because he refused to conform to a particular camp, he was rejected by both left and right.

The clash between the single tax and socialism and in the late 19th and early 20th centuries has parallels today with the clash between those who advocate for a carbon tax (or carbon fee-and-dividend) as the best way to control climate change versus those who believe the solution to be nationalizing the fossil fuel industry.

The history of the Soviet Union, communist China and other nations has shown that a state monopoly of all power is not a happy situation. Similarly, where is the evidence that nationalizing the fossil fuel industry would help reduce the use of fossil fuels? Many of the largest oil producers (including the largest, Saudi Aramco) are already state-owned. Do they demonstrate more environmental or social responsibility than their privately-owned competitors?