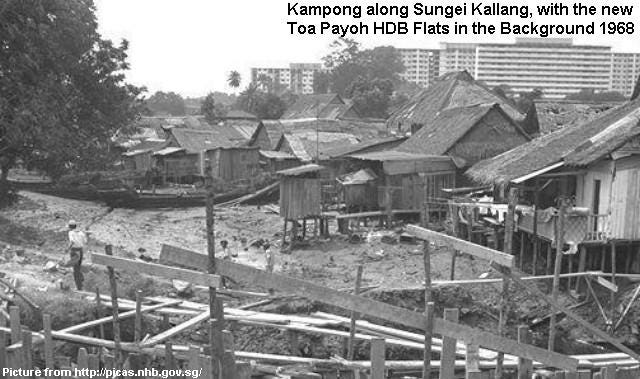

Singapore’s founding mythology goes as follows. After the departure of the British Empire from Singapore and its expulsion from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, the island nation faced a litany of challenges: a population with low literacy rates, living in kampong-style informal dwellings or crowded shophouses, with wide divisions across ethnic and political lines, under constant threat of military confrontation by large neighbouring states. Enter Lee Kuan Yew (LKY), Singapore’s first Prime Minister, whose bold statesmanship would rapidly propel the ‘little red dot’ to become a unified, multicultural, prosperous nation. At least, that’s the story the nation tells itself. For the most part, this narrative is correct: Singapore today is world-renowned for its competitive business environment, sustained by the culinary delights of hawker centers, clean streets and lush greenery, all knit together by an efficient transportation network.

Less agreed-upon is the question of how exactly this was achieved. Libertarians like to associate Singapore’s success with laissez-faire capitalism; those on the left argue that this perspective ignores Singapore’s bold history of industrial policy. As a matter of fact, both of these narratives-of-convenience overlook the vital core of Singapore’s economic policy. In this article, I’ll demonstrate that the key factor behind Singapore’s success is a set of policies firmly guided by the Georgist mindset of capturing and sharing land value. We will look at the way in which Singapore’s land was restored into public hands, deployed to build wealth, and redistributed through a near-universal program of subsidised housing.

The basic ideas of Henry George have been implemented, in effect .... and interestingly constitute the core of economic and social policy for Singapore.

-Phang Sock Yong, Professor of Economics, Singapore Management University

How Singapore Recaptured Land Value

To many Georgists, 1965 Singapore may have appeared poised to repeat the mistakes of many states gone before. Fewer than 10% of the population owned property; this small group was likely excited to extract rents from kampong-dwellers and enjoy speculative growth in the value of their land as Singapore developed. But that was not to be Singapore’s path.

Instead, in 1966, the government passed the Land Acquisition Act, granting broad powers to acquire land “for any public purpose”. Crucially, the rate of compensation to be paid to landowners was fixed at the land’s value on the ‘statutory’ date of 30th November 1973. Freezing the price of land immediately sent a strong signal to landowners that speculation was not going to be a lucrative business in Singapore, and that they’d better find a more productive pathway to profit. At the same time, Singapore introduced development charges which require landowners to pay a levy when the value of their land is increased as a result of planning permission being granted. Current rates are set to capture at least 70% of the land value uplift, which generates land revenues while also discouraging landowners from speculative lobbying over development rights.

These key policies, implemented in the early days of Singapore’s independence, are Georgist to their core. Singapore immediately recognised the need to capture land value for public purposes, the economic threat posed by land speculation, and the injustice of private landowners profiting from government actions. Lee Kuan Yew explained that the above policies were explicitly intended to prevent landowners receiving unearned windfalls:

“First, that no private landowner should benefit from development which had taken place at public expense; and secondly, the price paid on the acquisition for public purposes should not be higher than what the land would have been worth had the Government not contemplated development generally in the area.”

Singapore’s government proceeded to engage in an aggressive process of land acquisition, raising the publicly-owned share of land from 44% in 1960 to 76% by 1976. Today, more than 90% of the land is owned by the state. While many Georgists may balk at the idea of the government controlling so much land, to LKY’s credit, he immediately set about having land rights auctioned off for private use through the ‘Government Land Sales’ program. Land was typically sold on 99-year leases, after which it would revert back into public hands. Again, this sent a clear message to landowners that speculation was not going to be profitable long-term.

Further sources of land-related tax revenues include stamp duties on property transactions and annual property taxes which are levied as a percentage of the annual rental value of a property. Electronic Road Pricing (ERP) charges drivers each time they pass through gantries on heavily-used roads, with prices being higher during rush periods. Although not a policy immediately associated with Georgists, congestion pricing is an excellent example of the application of Georgist analysis to particular economic issues; it requires drivers to compensate society for the privilege of excluding other drivers from scarce slots of space-time on the road. Singapore’s ERP is considered world-class, and has enabled average speeds on expressways to be maintained as high as 65km/h even during peak periods.

Land became a factor of production, a driver for economic growth unhindered by social and political disputes over ownership. There was no landowners’ class to hold back economic development. Government land serves the whole economy as well as public finance, creating the ideal conditions for public housing.

-Anne Haila, once called “the most important Georgist in the World”.

Using Land Rents for All of Society

The considerable revenues generated by the above policies have not been frittered away. Instead, they have been put to work for the benefit of all Singaporeans. Proceeds from land sales form part of government reserves, and have been funneled into Singapore’s two sovereign wealth funds, GIC and Temasek. Together, these funds have amassed a net asset value of US$740bn, more than double Singapore’s GDP. This comprises the fourth-largest sovereign wealth fund on the planet, among the ranks of Norway (another Georgist success story), petrostates like the UAE, and China, with a population 250 times larger than Singapore.

GIC & Temasek put these funds to work earning returns on behalf of all Singaporeans. One quarter of Temasek’s portfolio is invested within Singapore, providing capital which helps grow employment and productivity among domestic firms such as DBS Bank, Singapore Airlines and Sea. Like most large funds, they appreciate the value of real estate, and have around US$71bn invested in property, including in one of Asia’s largest real estate companies, CapitaLand. Singapore’s reserves are also deployed for land reclamation and the creation of underground space, with the land value which is created accruing fully into increased reserves.

Freeing Capital & Labour

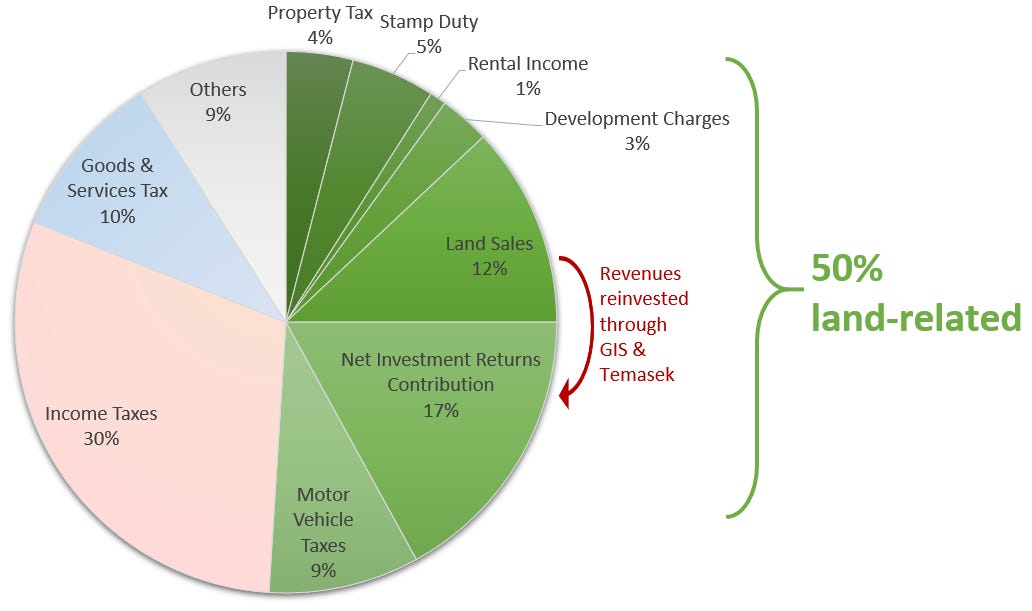

The substantial revenues generated by the above policies of land value capture have provided a huge amount of financial freedom to the government of Singapore. Half of GIC & Temasek’s returns are recycled into the government’s operating budget as the Net Investment Returns Contribution. As depicted below, fully half of all government revenues derive from land in one way or another.

Being awash with cash, the Singapore government is able to maintain remarkably low taxes on both labour and capital, while still returning a balanced budget. Corporate tax rates are 17%, below the 21% charged in the US, which has enabled Singapore to market itself as a highly attractive destination for multinational corporations, draw high levels of foreign investment and establish itself as a global business hub. Likewise, incredibly low rates of income tax combined with a luxurious standard of living have enabled Singapore to poach talented workers from around the globe (and also, me!). Around 40% of Singapore’s population are foreign-born.

The median full-time worker in Singapore earns a gross wage of US$42k per year, and is required to pay only US$1,200 in taxes, an average tax rate of only 3%. Knowing they will get to keep such a large share of their wages, the local workforce are highly motivated to work and develop their skillset. Prior to the pandemic, unemployment rates averaged only 2%. 8 in 10 Singaporeans aged 25-34 have attained tertiary education, higher than any country in the OECD.

Thus, we observe that shifting the tax base off workers & their savings can free labour and capital to be put to their most productive use, generating prosperity for the nation as a whole. Singapore verifies Henry George’s predictions on the results of shifting a tax base to land: “With all the burdens removed which now oppress industry and hamper exchange, the production of wealth would go on with a rapidity now undreamed of”. The country’s GDP grew by 6% a year on average over the last 50 years.

Sharing Land Rents with Subsidised Housing

The social benefits of Georgist policies are not purely limited to economic efficiency. The substantial revenues that can be generated from land provide many opportunities for redistribution in ways that will ensure a baseline level of wellbeing for all members of society. In Singapore, this has taken place through near-universal access to subsidised housing.

Public housing in the Singapore context refers to housing built by the Housing and Development Board (HDB) and ‘sold’ to Singaporean households under 99-year leases. New HDB flats are sold at subsidised prices, and a range of grants are available. For example, couples applying for a Build-To-Order (BTO) flat can obtain the Enhanced Housing Grant of up to US$60,000 depending on their income. In the most recent BTO exercise, 4-room flats (which typically have 3 bedrooms and 2 bathrooms) were being offered for between US$200,000 and $380,000, excluding grants. Including grants received, households may even find themselves paying less than construction costs.

Revenues from one project are recycled into subsequent waves of development, ensuring a constant supply pipeline; 750,000 units were built between 1970 and 2010. This has helped to keep house price growth rates relatively low; the SRX property index for resale (open market) properties has risen by only 3% per annum over the past 25 years. Homeownership rates have risen from 30% in 1970 to 90% by 2017. Marriage has become so strongly associated with immediate access to homeownership that marriage proposals in Singapore are often said to be phrased as “want to BTO together?”. Even the remaining 10% of households who truly cannot afford homeownership are eligible for rental units offered by HDB at subsidies rates, through the Public Rental Scheme. Assuming that the poorest 50% of all households reside in 4-room or smaller HDB flats, they own around 25% of the nation’s housing wealth, which closely approximates Thomas Piketty’s ‘ideal society’ distribution of wealth.

Such policies effectively share the nation’s land rents across the entire population by reducing the burden of housing costs, which is most households’ largest expenditure item, globally. This helps cushion Singaporean households against the threat of rising land rents as the country develops, which is the cause of much displacement and homelessness worldwide.

Purity-Testing Lee Kuan Yew

Despite the above successes, Singapore falls short of ‘pure’ Georgism in a number of ways. First, Henry George did not advocate public ownership of such large volumes of land, instead preferring private ownership paired with a tax to capture land rents: “I do not propose either to purchase or confiscate private property in land ... it is only necessary to confiscate rent.” High rates of public land ownership can raise concerns around inefficient land use decisions, such as those seen in the perverse population-density gradient of many former Soviet cities and still somewhat seen in Singapore. While the land sales program does incorporate some market feedback into land use decisions, mechanisms for private allocation are likely more desirable. Likewise, while stamp duties ultimately capitalise into land values, they also reduce household mobility and result in inefficient matching of households to locations.

Second, despite the financial freedom created by the policies described above Singapore still falls short of full capture of land rents. Leasing land for 99 years at a time only enables the public to accrue the present value of future land rents at the moment of sale. This is followed by a long period of time over which the true rental value of land can increase without being captured. This could be mitigated by shorter lease periods, or including mechanisms for increasing lease rates in areas where land value has risen. One way of achieving this is to increase the annual property taxes charged to homeowners, which could simultaneously be made more purely-Georgist by calculating taxes only on the basis of the underlying land value, rather than also including the dwelling built on top of the land.

Finally, as many land leases head into their final 30 years of life, many Singaporean homeowners are concerned that the value of their homes will decline to zero. Unfortunately, the government is beginning to show some signs of bending to the political will of homeowners, and has used the Selective En Bloc Redevelopment Scheme to renew ageing HDB blocks and grant displaced homeowners with brand new 99-year leases. All homeowners in these blocks enjoy a large windfall gain at public expense. I would instead advise the Singaporean government to allow ageing leases to expire, and maintain the stance that land rights are not granted in perpetuity. Those households who do face financial stress as a result of their expired lease can best be targeted on the basis of their specific socioeconomic characteristics.

Lessons from Singapore

Singapore clearly provides a shining example of the prosperity that can arise from Georgist principles put into practice through pragmatic policy. In the early years of independence, land value was rapidly restored into the rightful hands of the public. While widescale land acquisition may be beyond the political appetite of Western voters, the use of a statutory date demonstrates one way in which speculation can be stopped dead in its tracks. Georgists who are willing to accept some compensation of landowners during the transition to land taxes could use a similar method to determine an acceptable payment based on past property values. Singapore’s development charges demonstrate a Georgist tool for capturing some of the windfall gains earned by landowners as the result of planning changes. Cities with clogged road networks can copy Singapore’s congestion pricing and improve efficient use of this public resource.

Singapore also serves as a model of the way in which proceeds from land sales can be invested in the interests of all Singaporeans through a sovereign wealth fund. Likewise, revenues from all of these Georgist policies provide the bulk of Singapore’s budget and reduce the tax burden placed on workers and their investments, providing a boost to economic growth. Finally, Singapore’s model of highly-subsidised access to HDB housing serves as a unique example of the way in which the revenues from land value capture can be redistributed throughout the population, ensuring a baseline level of prosperity for all members of society.

Readers who want to learn more about Singapore’s unique brand of Georgist policy should read this article by the brilliant Phang Sock Yong, and this book by the late Anne Haila.

Excellent read!

Wonderful article.

I think a key to Singapore's success is its strong maintenance of public order. So much of "land value" is really "do well behaved people live here." In Singapore you know that no matter who your neighbors are things will be alright. In America we have a dangerous underclass and an awful lot of real estate speculation centers around who ends up with that hot potato. In America public housing has quickly collapsed into underclass housing, we couldn't run a Singapore type system.

I lived in Baltimore for a long time and Baltimore has insanely high property taxes, over twice what the surrounding county has. The high taxes mostly get squandered by the city government (no model of Singaporean competence). Meanwhile, there were huge issues with crime and underclass behavior. The result is that people left the city to settle in the county.

I'd say what Singapore has accomplished is a package deal. It didn't run a certain kind of property use scheme. It had a whole model of governance that made it work.