Georgism through Land Leasing

Municipal Land Leasing is real, effective, and very, very Georgist

Over the years I’ve often heard Georgism described as the greatest set of policy ideas that will never really be tried. In these conversations, though, the commentator is usually referring to a narrow conception of Georgism, something like 100% land value taxation. While it’s true we’ve never seen policy like that in the U.S., this view is reductive and misses the very real examples of Georgist policy that already exist today. Georgism isn’t about land value taxation, per se. It’s about the appropriation of land value for the public benefit. 1And, as it turns out, once you properly see the cat, you realize there’s more than one way to skin it. Our story today is all about one of these other ways; to wit, municipal land leasing.

Land leasing has proven to be the most politically durable approach to Georgism over the course of the last century. In this post, we’ll take a look at some of these examples, explore how they work in practice, and consider what they mean for implementing a broader raft of Georgist reforms going forward.

New York’s City within a City

Our story begins in New York during an economic low point in the mid 1960s. At the time, policymakers at both the state and municipal level were interested in revitalizing the city’s fortunes and were pursuing a development strategy of luring white-collar employers back into New York’s urban core.2

One such project was the original World Trade Center (WTC). Construction created a problem that was eventually turned into an opportunity. Preparing the site for the 110 story buildings that would eventually go up required digging deep into the earth (tall buildings require deep foundations) and figuring out what to do with all the excavated rock and dirt.

Enter New York State Governor Nelson Rockefeller.3

Rockefeller was also keen to see NYC bounce back, if not as a matter of pure policy, then as a feather to put in his cap ahead of a presidential run. His big idea was to take all the excavated material from the WTC dig site and use it for a land reclamation project that would serve as the basis for a state-led real estate development meant to help revitalize downtown Manhattan. This is the origin story of Battery Park City.

Battery Park City is a 92-acre neighborhood on the southwest side of the island of Manhattan. The land created via reclamation was placed under the stewardship of the Battery Park City Authority (BPCA) which was given responsibility for raising capital and managing the neighborhood’s development.

As a New York State public-benefit corporation, the BPCA was able to issue debt more aggressively than a municipal government or state agency. Because the BPCA lacked direct access to tax revenue — public-benefit corporations don’t get taxing authority — it structured its bonds around the revenue it could generate post-development; revenue generated, in no small part, by long-term land lease agreements with developers.

The typical BPCA land lease runs for 99 years, although several have already been extended out to 120 years. These leases also include pre-set reassessment points. For example, a developer might lease land worth $3M in year zero and agree to pay 5% on that value as their land fee. At some designated point, say year fifteen, the land gets revalued at $5M and the developer’s land fees now become 5% of the new, higher value.

This allows the BPCA to recoup increasing land values and do so in a way that’s slow and predictable for developers.

Now, time for caveats. The BPCA revenue model falls short of the Georgist ideal. On top of leasing fees, it also charges something functionally, but not legally, equivalent to taxes on improvements called PILOT fees.4 So, in reality, it’s running what would be better characterized as an aggressive split-rate system. That said, this system seems to work pretty well — at least from a financial perspective.

In FY2023, the BPCA generated about $400M in revenue. It spent roughly half of that on debt service, infrastructure, and services like maintenance of its public parks. The other half it remitted back to the City of New York.

As cool as the story of Battery Park City is, it admittedly required the involvement of (2) Rockefellers, 92 acres of rubble with no place to go, and a particular moment in New York City’s political and economic history. Thankfully, it’s not the only example we have to talk about.

Virginia Leasehold

Falls Church is a 2 square mile community tucked away in the northeast corner of Virginia, just a few miles outside the U.S. capital in D.C. The city traces its origin all the way back to 1734, though its incorporation as an independent municipal entity happened in 1948.5

In 2017, the town decided to rebuild the local high school. The existing facilities were built in the 1950s and the cost of maintenance was becoming so high that it became economical to rebuild the facilities from scratch. The city had two options:

Option A: increase everyone’s property taxes by $1,050

Option B: use 10.3 acres of publicly owned land for redevelopment, monetize through land leasing, and only raise everyone’s property taxes by about $280.

After a voter education campaign and a series of public hearings, the council moved forward with option B.

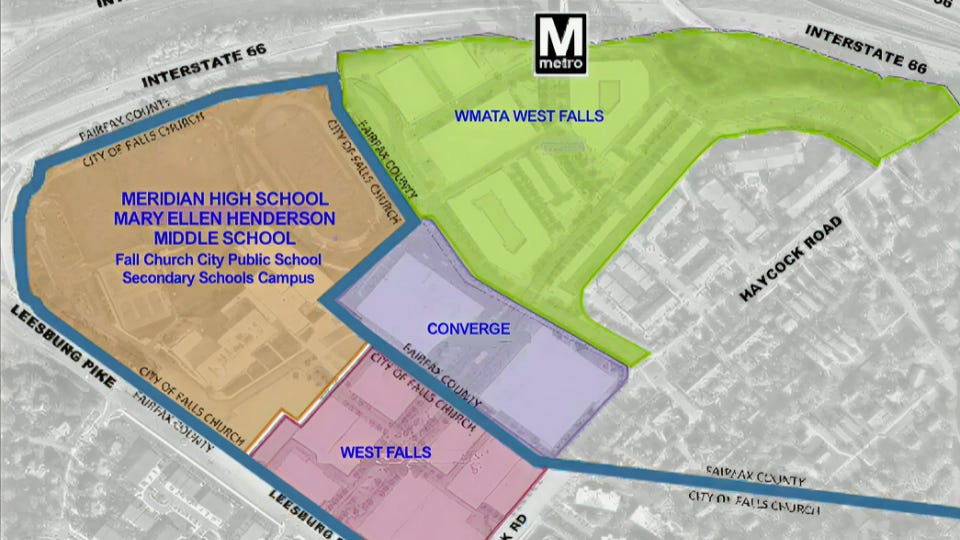

When the city rebuilt the local high school, they sectioned off a portion of the land (labeled “West Falls” in the image below) and transferred ownership to the newly created West Falls Community Development Authority (CDA). The CDA was empowered to issue bonds and enter into a lease agreement with a development partner, eventually choosing FCGP Development LLC.

The CDA structured their agreement around two lump sum payouts plus a yearly lease fee, and eventual repossession of the land and all improvements at the end of the lease term.

Phase 1 payment: $25.5 million (roughly 57% of the land’s assessed value) paid out over the first six years of the lease. Grants developer rights to build on most of the property (3 acres held in reserve).

Phase 2 payment: $10 million or the assessed value of the reserved 3 acres (whichever is greater), payable after the Phase 1 completion. This structure ensures the CDA captures any unanticipated land appreciation.

Annual lease payments: Annual lease payments starting at $200,000 and increasing 2% annually, with a one-time $25,000 step-up in 2030. Payments starting in 2026.6

Repossession of land and improvements: The final cherry on top comes at the end of the lease period. Barring renegotiation, everything FCGP Development has built defaults to CDA ownership.7

Here again, this is not textbook Georgism. The city will still levy property taxes on improvements, collect sales taxes from businesses (including hotel taxes), and, obviously, the lump sum structure of the lease payments is not textbook Georgism. And yet, it is Georgist policy. The city is not selling the land, it’s being compensated for its use. Though the land is priced against current expectations, there are mechanisms for capturing unexpected upside. And, most importantly, in a hundred years, the city will still have a revenue generating asset producing wealth for the great grandchildren of the people living in Falls Church today.

Lessons Learned

Battery Park City and Falls Church aren’t the only examples we could look at. Roosevelt Island is another NYC example of leasehold Georgism. The Boston Planning and Development Agency largely self funds by monetizing its 13 million square foot real estate portfolio. And, if we’re willing to entertain a non-U.S. example, the Squamish are in the process of funding their entire nation’s medical system through a ~10 acre mixed-use development in Vancouver. Elsewhere in the heartland of privatized land rents (aka California), officials on the San Francisco United School Board have expressed interested in developing underutilized district land to me in one-on-one conversations. Similarly, one of the candidates for the California Lieutenant Governorship wants to do the same with land owned by California’s two public university systems.

That’s all to say, we have various examples of public land leasing, both existing and prospective. At this point, though, we might ask what to make of it all.

To start, I want to reiterate that Georgist policy exists, it’s just that it more commonly looks like the pre-appropriation via land leasing than it does reappropriation through land value taxation — and this is for an obvious reason. In the U.S., we’ve created an electorate of owner-occupier landowners. Homevoters ended Pittsburgh’s split rate system. And a statewide tax revolt created the abomination that is California’s hobbled property tax system. That’s not to say there’s no hope for land value taxation, especially where it can be implemented as a neutral change for homeowners. But if we acknowledge how hostile the political-economy of land use in the U.S. has historically been towards LVT, we can start to see how land leasing bypasses those structural impediments.

These land leasing examples also remind us how messy actually implemented policy is always going to be. There’s no one weird trick that land rentiers hate that delivers a world where all rents are appropriated for the common good and private effort remains untaxed. And as Greg Miller has pointed out in the past, even if you could press a button and make that change overnight, you’d cause an international financial collapse which would, in fact, be bad. Instead, policy will always be incremental. When we accept that fact, it makes us better at taking the bite at the apple we can take, whenever and wherever we can take it.

In a similar vein, Georgist policy will never be implemented because it’s Georgist; Georgist measures will get implemented because they solve specific policy problems in ways that are politically tractable. Though it’s a story from a much more technocratic age, Battery Park City’s leasehold financing was set up to pay for a development strategy which the Governor of New York thought would revitalize NYC and help him with a presidential bid. In a different institutional context, Falls Church pursued leasehold development to defray the cost of investment in public education (investment the voters wanted, but were very happy to pay for in some way other than out of their own pockets).

People don’t experience outcomes in either the long run or the aggregate. We need to connect policy solutions to tangible outcomes. Our examples of successful land leasing are good reminders of that fact.

Leasing vs Taxation

Before we conclude, it’s important to acknowledge that land leasing and land value taxation are not perfect substitutes.

Undertaking leasehold monetization requires a competent development authority that’s able act as the lessor and select development partners. Development authorities also need the ability to issue debt to finance the public infrastructure necessary for private development on leasehold land (roads, power, sewage, etc). In sum, this requires the establishment of a professionalized bureaucracy to lead development and oversee the leasehold property in perpetuity.

Similarly, leasehold development implies greater government involvement in urban development as compared to a taxation based approach. The typical American municipality, whether they realize it or not, manages the development of the built environment as a sort of arm’s length series of operations. Euclidean zoning, non-zoning ordinances, and the shape of transportation infrastructure determine what developers are allowed to build and also what they can do so profitably. In this standard pattern, the built environment is a second order outcome of the conditions and incentives created by municipal authorities.

In our two main examples, however, neither BPCA nor the Falls Church CDA were just selling access to land and letting developers take it from there. Both had opinions on exactly what kind of development they wanted to see and put out RFPs as part of the developer selection process. Some might argue this is a very top down development approach and perhaps that is fair; but whether it’s truly top down or not, decision making was guided by the need to maximize lease values (or at least maximize them to the point they could pay for what they were intended to pay for). Whether this active role is desirable depends on one’s view of state capacity and urban planning—but it’s a distinct feature of the leasehold approach that advocates should understand.

Conclusion

Georgism exists. It’s just that many of our existing examples look like leasing public land instead of taxing private value. While there’s a bright future for LVT style reforms, if we recognize public land leasing as a complementary policy we can open up the aperture of our imagination and start to see a wider array of political opportunities for reform.

As advocates, this means recognizing more opportunities to deploy Georgist solutions to policy problems of political import — and, in so doing, further the work of coalition building that will be required for ongoing reform.

If we take the analysis all the way to its logical conclusion, Georgism also has things to say about natural resource exploitation, intellectual property, and anywhere else in the economy where we might find instances of rent seeking.

I don’t buy into white-collorization as the right way to think about creating urban prosperity, but that was the mode of thinking in New York at the time and informed what they saw as progress and, as a result, what got built as well.

As it turns out, the man behind the WTC project was none other than David Rockeller, Nelson’s brother. American politics is all a lot more Medici than we’d sometimes like to admit.

Payments In Lieu of Taxes, or PILOT Fees, are payments made by property owners to the BPCA. Like property taxes, they’re based on the assessed value of the real property. Unlike property taxes, however, they’re a contractual agreement upon payment, not a statutory obligation. That gives the BPCA flexibility (during COVID, they were able to unilaterally pause payments to prevent bankrupting property owners) and means disputes are a matter of commercial law. And, of course, these payments are based solely on the value of buildings as the property owning payees have no title to the underlying land.

The town’s backstory is about as racist, classist, and exclusionary as most of American land use, which is to say, very. I’m given to understand the existing city leadership is intent on reckoning with that past in various ways, perhaps the most tangible of which is through pro-housing land use policy.

This mechanism puts the onus on the developer/lessee to monetize the land fast (and successfully) enough to stay ahead of the payment schedule. In the Falls Church example this fee is low enough (relative to the lump sum payments) that I doubt it’s determinative, but it’s an interesting way to approach pricing strategy for land leases.

This part likely sounds more radical than it actually is. Most commercial developers assume a building will fully depreciate over the course of 20-30 years; over the life of the West Falls lease, there will likely be a couple rounds of development, with monetization/depreciation timed to coincide with the expiration of the lease. The important point is that the city retains control of the land and has the incentive to continually monetize it (i.e. keep it in productive use).

This is quite similar to what they do in Singapore which works pretty well for them. Instead of the city selling land, most of the land is publicly owned and leased to corporations, individuals, etc for 99 years.

Excellent Post!!

Another way to capture rent is to tap into Henry George's greenback history:

https://monetary.org/articles/henry-georges-concept-of-money/