There is never a dull moment in South Korean politics. Six months ago, the conservative President Yoon Suk-yeol accused members of the National Assembly of being “despicable pro-North Korean anti-state forces,” declared martial law, and deployed the military to block representatives’ access to the Assembly building. Mass protests immediately erupted and Lee Jae-myung, leader of the opposition Democratic Party of Korea (DPK), live-streamed himself climbing a fence to get into the Assembly building and called on other representatives to join him. Once inside, a supermajority1 immediately voted to cancel the martial law declaration, and later impeached President Yoon, triggering a snap election.

A surprisingly straightforward race culminated last week with Mr. Lee emerging victorious, with his past support for land value tax (LVT) and universal basic income (UBI) being seen as cause for celebration among some Georgists.

So let’s get to know South Korea’s new President, Lee Jae-myung. We’ll trace his political journey, explore the state of housing & taxation in South Korea, and ask whether we can call him the world’s first Georgist president.

The Political Journey of Lee Jae-myung

Mr. Lee’s personal political philosophy of Eokgang Buyak, meaning “supporting the weak and protecting them from the strong” can be traced to his early life. Born in 1963 to a poor family in the provincial city of Andong, Mr. Lee left school as a teenager and worked in necklace and rubber factories where he received consecutive hand injuries. Forced by disability to consider new careers, Mr. Lee moved to Seoul, earned a law degree, and then worked as a human rights lawyer for Minbyun, seeking social justice through legal activism. For example, he successfully fought Seongnam City into redeveloping its municipal hospital in the early 2000s.

Shifting his career into direct politics, Lee would go on to win election as Mayor of Seongnam in 2010, where he would restructure city finances and use the savings to expand social welfare programs including a universal basic income (UBI) for young people, free postnatal care, and expanded funding for the aforementioned hospital. It was here that Mr. Lee developed his reputation as a bulldozing public administrator intent on achieving his campaign promises, and as a straight-talker who is adept at using social media to communicate with voters.

After a three-year stint as Governor of Gyeonggi Province (which surrounds the Seoul metro area), Mr. Lee was nominated as the 2021 presidential candidate for the center-left DPK, and campaigned on promises to boost growth and reduce inequality through aggressive spending, specifically through universal access to welfare. His suggestion that these programs be funded from taxes on carbon and land caught the attention of online Georgists. While he narrowly lost that election (by less than 1%), Mr. Lee immediately won a seat in the National Assembly and retained his position in the party, returning as the DPK candidate in last week's election.

This time around Mr. Lee emerged victorious after running a campaign promising political stability and economic growth; universal access to housing, medical care, education, and public services (which he calls “basic society”); tripartite cooperation with the US & Japan; and a willingness to ease sanctions on North Korea in exchange for denuclearization. Absent any major scandals or coups, Mr. Lee will now serve a 5-year Presidential term.

But is he really a Georgist? And how likely is he actually to tax land and other natural resources? Before we answer these questions, let’s set the scene with a quick detour through housing and property taxation in South Korea.

Housing & Taxation in South Korea

Following the Korean War (1950-1953), the Republic underwent a rapid period of industrialization and urbanization. Nowadays, 8 in 10 South Koreans live in a city, and fully half of the population live in the Seoul metro area. Driving this urbanization was the rapid construction of self-contained apartment complexes, jump-started by the state-owned Korea Land and Housing Corporation and boosted by low-interest loans provided to massive development conglomerates which include familiar names like Hyundai and Samsung. Today, these iconic ‘apatu’ comprise nearly two-thirds of the housing stock nationwide (one in five are detached dwellings with the remaining 15% being row homes and other housing types).

More than one-third of South Koreans live alone and nearly two-thirds with family (living with non-relatives is very rare). Households are divided between three main tenures: 56% are owner-occupiers, 23% are renters, and 15% use the unique ‘jeonse’ system, in which tenants pay a large deposit (typically 60-80% of the property’s market value) which landlords can reinvest during the tenancy but have to return in full at the end of the lease.

Housing affordability is primarily a big city problem: house prices in Seoul, Busan, Incheon and Daegu are more than 3 times higher than in smaller cities. In Seoul, the median apartment price recently surpassed 1 billion won (USD$735,000), which is 14 times the average household income of 72 million won ($53,000). Rent for a one-bedroom apartment downtown is typically around 1 million won ($750), just under 25% of household income.

House prices throughout South Korea climbed slowly through the 2010s due to a combination of strong construction and lending restrictions aimed to prevent speculation. The pandemic triggered a mini boom and bust which saw house prices rise by 16% over the first two years, followed by an 8% decline over the next two. Housing construction also collapsed, with residential starts in 2023 falling to half of pre-pandemic levels, suggesting a supply shortfall that Mr. Lee would do well to fill.

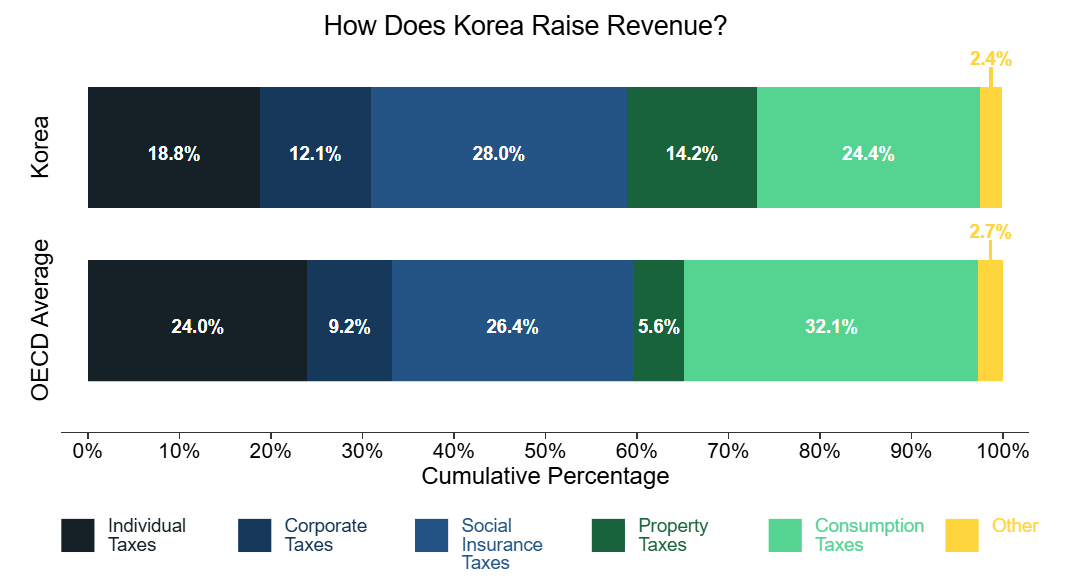

Typical of wealthy countries, South Korea has a broad-based tax system, including a 10% VAT on most goods & services, and steeply progressive taxes on corporate and individual incomes (which max out at 24% and 45% respectively). Notably, property taxes account for 12% of total government revenue, more than twice the OECD average. Buyers of property pay an Acquisition Tax of up to 7% for individuals and 12% for corporations. On an ongoing basis, property owners pay a Comprehensive Real Estate Holding Tax which ranges from 0.5% to 5% based on the total value of their holdings. Local governments are primarily funded by standard Property Taxes (on both land and buildings), which range from 0.1% to 5%.

It was in this context of rising housing costs and widening inequality that the public grew interested in the idea of a UBI funded by taxes on land, on which Mr. Lee campaigned in 2022. In that year, one analysis found that an effective LVT of 1.1% would generate revenues of 80 trillion won (USD$58.5 billion), enough to fund an annual UBI of 3.6 million won ($2,600) per household (5% of current incomes). They found it would lower house prices, raise the net income of 85% of all households, and reduce every measure of income inequality2.

“Redistributing gains from the [land] tax in the form of land dividends would benefit the overwhelming majority of Koreans” - Young Seong-yoo et al. (2022) Gyeonggi Research Institute

The First Georgist President?

Georgists should see much to celebrate in Mr. Lee’s politics. He is generally supportive of markets and free trade, but supports public intervention to prevent rent-seeking and redistribute monopoly profits, and frequently cites inequality as the root cause of corruption and social division. Carbon taxes are his preferred solution to climate change. His roadmap for achieving universality includes a Wind/Sunlight Pension’ whereby the revenues from public wind/solar projects are shared as a dividend with the local community.

But for Georgists, the most exciting aspect of Mr. Lee’s politics is that in the 2022 election, he explicitly campaigned on using a land tax to fund a UBI, arguing that this would help discourage real estate speculation and reduce wealth inequality. Sadly he lost that election, and walked back his support for the land tax during this year’s campaign, citing public backlash.

So should Mr. Lee be considered the first Georgist president? In my opinion: yes! Sure, skeptics might reasonably argue that Mr. Lee only ever saw land taxes as a way to achieve the “universal basic society”, which is his true passion. But Mr. Lee clearly recognizes the role of land speculation in wealth inequality, refers to land rents as “unearned income,” and respects land as a public resource under the Constitution. Perhaps his most Georgist credential is the fact that last year Mr. Lee was stabbed in the neck by a real estate agent.

“In order to realize the concept of public land ownership, block unearned income, and suppress real estate speculation, a land holding tax should be imposed”. - Lee Jae-myung, Policy on Basic Income, Press Release3. July 22, 2021

But will he actually pursue Georgist policies? Maybe. Mr. Lee prides himself on fulfilling his campaign promises and holds a DPK majority in the National Assembly. As he follows his “roadmap to a basic society” he will inevitably require new sources of funding, and will hopefully return to the idea of land taxes. At the very least we are likely to see further redistribution of resource rents through the sharing of renewable energy revenues.

However, there are significant risks that Mr. Lee’s economic reforms will fall by the wayside. Foreign policy will be his first priority as he looks to manage North Korean nuclear ambitions and normalize trade relations with the US. Mr. Lee is also entering office amidst several pending legal battles, and although the Constitution protects a sitting president from prosecution, any fresh scandals risk undermining his mandate. Critically, the DPK’s failure to tackle Seoul’s housing crisis cost the party dearly during the 2022 election. Hopefully, Mr. Lee will recognize that voters are eager for honest leadership, political stability, and meaningful economic reform.

The time is ripe for South Korea to tax land, build housing, and redistribute resource rents.

(Stephen Hoskins is the Director of Community Research and Engagement at the Progress & Poverty Institute)

Including 18 members of President Yoon’s own party, the PPP.

Including the Gini coefficient, the income quintile share ratio, and the relative poverty rate

기본소득 정책공약 발표 기자회견문, 이재명

Some anonymous comments from an anonymous American who lives in ROK and speaks Korean:

I think the article's general description of Lee, housing, and taxation is accurate, but oversimplified. However, I don't think the oversimplification can be avoided.

I see Lee more as an economic social justice warrior, and to whatever extent he embraces Georgism, it is only with economic social justice in mind. I'd say Lee is more of a Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren type, though more practical, and less crass. I think his adoption of anything Georgist is more coincidental in his pursuit of economic equity. But, maybe that means he'd be more receptive to it, as and ideology, than other politicians.

Searching for a few similar Korean terms I found one from about 3 years ago: https://www.chosun.com/economy/real_estate/2021/08/03/PBYVRNKXVRGPTDTJGCQC7ZBLHI/ It's specifically about Lee and Georgism. There's an accompanying video too: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xiPq9nymHao It's quite entertaining and encouraging to hear native Koreans mentioning Henry George by name. :-)

I don't think Georgism has yet reached the mainstream public consciousness that I'm typically surround by, but, to be fair, that doesn't appear to have happened in the U.S. either. Korea in 2025, through the Lee administration, just might be the right time and place for the ideas of Georgism to gain political legitimacy.

My wife and I were both not familiar with any policy of his specifically incorporating LVT, until reading the article. The sources appear accurate, but land value taxation was not a prominent mention in any of the media we consumed. My wife's aunt and uncle are big Lee advocates, so I'll have to ask them if they were aware of any LVT policies of his.

What I'd add to anyone reading the article is to understand how, like in the United States, housing in Korea is being (ab)used to obtain and preserve wealth. There is a significant segment of the Korean population that derives much of their wealth from real estate investment, speculation, and rent seeking. Just as in the United States, the average home owner in Korea is also engaging in that game, by signing themselves up for low-interest, very long-term mortgages, in the hope that over the long term, inflation will erode their principle. That has worked pretty well for the past 20 years, but I think it may be coming to an end, especially as the elderly begin to pass on, and all of their assets get put on the market to fewer and fewer younger buyers.

gotta learn korean.