DeSantis is Half-Right About Property Taxes

The Florida Governor is trying to undo Florida’s property taxes. Taxes on buildings are bad. Taxes on land are not.

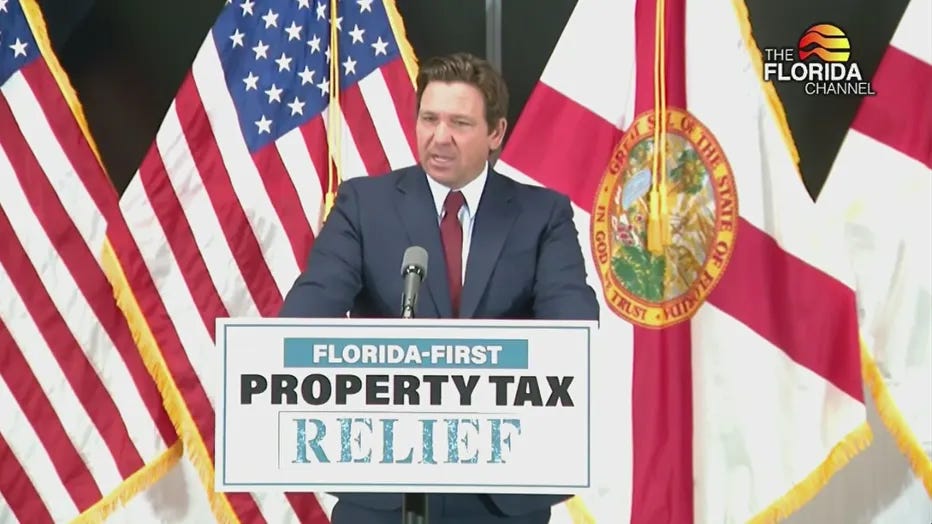

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis wants to eliminate property taxes. While he’s not the first governor to attempt this (see Indiana and Texas, among others), his proposal for complete elimination has gone the farthest.

In a recent roundtable in Jacksonville focused on property taxes, he defended his stance with the following reasoning:

“You go buy a TV from Best Buy and pay a sales tax on it… And then you watch it. You don’t keep paying taxes on it indefinitely.”

Good and Bad Taxes

As far as TVs goes, this analogy makes perfect sense. A TV set is a manufactured good that depreciates in value over time; levying an annual holding tax on such an item makes little sense. When it comes to tax policy, buildings are in the same boat; they are constructed things, and likewise subject to depreciation.

However, real estate doesn’t just concern buildings, it concerns buildings and land, and this is where DeSantis’ analogy breaks down. Unlike buildings, nobody produces or manufactures land, nor does land depreciate over time the way buildings, cars, and TV sets do.

The trouble with the property tax is that it’s two taxes in one: a tax on buildings, and a tax on land. The building tax is bad, and should be eliminated for exactly the reasons DeSantis says.

The tax on land is good, however.

Eliminating the land portion of the property tax would backfire, undermining DeSantis’ goals of fostering economic growth and housing affordability. Eliminating it would set Florida on the same disastrous path California has been on ever since the passing of Proposition 13, which among other things, had the effect of drastically reducing the effective tax rate on much of the state’s most valuable land. The resulting inflation of land prices has caused California to lead the nation in homelessness and housing unaffordability, with sustained out-migration significant enough to trigger a decline in congressional and electoral college seats in the 2030 apportionment.

Another possibility is simply that DeSantis will encounter a nasty and embarrassing inter-Republican fight that stymies his goals. This is exactly what we just saw play out over the last four years in deep-red, traditionally anti-tax Texas, when state electeds gunning for property tax elimination failed in two back-to-back legislative sessions after local governments revolted.

Nevertheless, DeSantis is right about the building portion of the tax. He can and should eliminate that.

The Building Tax is Bad

The governor wants people to invest in Florida’s growth. However, investment always seeks the path of least resistance, so if a passive investment is available that is more lucrative than a productive investment, more money will flow towards the passive investment.

Let’s say I put $200,000 into the productive investment of building construction in Florida. In 20 years, I will still be paying building taxes on my investment from two decades ago, regardless of whether I made a profit on the investment.

Let’s also say that on the same day, my neighbor put $200,000 into the passive investment of the stock market. In 20 years, he will pay taxes only once, and only on his realized gains.

Relative to passive investment, building is punished, all while housing costs are soaring. As the saying goes, “if you want less of something, tax it.” Taxing construction results in less construction.

The impact of the building tax is not small. With Orlando’s effective property tax rate of 1.2%, the Net Present Value of 30 years of taxes comes out to nearly 20% of the initial construction cost.1 Removing the building tax would instantly free up 1.2x more capital to build bigger, better, or simply more buildings.

This freed-up capital applies to all development types. An additional 20% investment in developing a single-family house can mean an extra bedroom or a more luxurious kitchen. For larger developments, eliminating the building tax would allow a 100-unit multi-family housing development to expand to 125 units. Applied statewide in Florida, removing the building tax could increase housing units by 20%. Given nearly 10 million existing housing units, this could result in 2 million more units in Florida than currently exist.

Much talk of housing affordability is dominated by zoning reform, while the effects of tax policy are neglected; eliminating building taxes would be a straightforward win for housing policy. DeSantis is correct to point this out, consistent with his stated purpose of spurring more development.

However, in pushing to eliminate both halves of the property tax–building and land taxes, DeSantis sets the stage for undermining his own goals.

The Land Tax is Good

Although they’re packaged together as one, the land tax behaves very differently from the building tax.

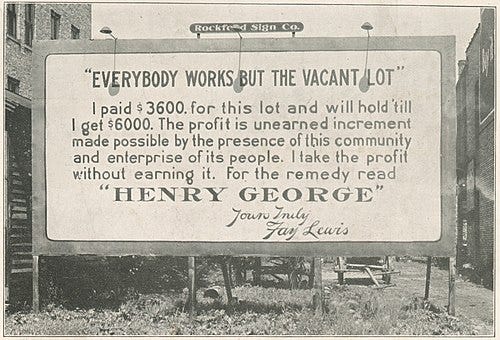

To understand why, let’s add a new person to our investment example from before–a corporate land speculator, who buys a vacant plot of land in the urban core for $200,000.

Unlike me, who constructed a building, and my neighbor, who provided capital to businesses, the land speculator does nothing, and keeps the land vacant for 20 years. During that time, a void of development in the urban core forms thanks to other speculators just like him, even as hundreds of thousands of people migrate in, and hundreds of millions and even billions of dollars in civic investment pour into the urban environment–the story of many Florida cities.

After twenty years, that land will be worth much more, even though the speculator did nothing. Even worse, the speculator prevented others from putting that incredibly valuable land to productive use. And yet they were richly rewarded for their non-efforts.

When I manufacture a product, I create value by providing it to people. When an investor gives capital to a business, they rightfully share in its profits because the business couldn’t get off the ground without the investment. Who is primarily responsible for the increase in value of urban land?

The answer is the community that surrounds that land. When thousands move in, roads are paved, streets kept safe, and parks kept clean, land grows in value. A piece of land on its own is worth very little without roads, sewage, parks, and other people and businesses in the area–which is why land in the middle of the desert is practically free, and land in the middle of cities is worth far more than land in the suburbs.

With a low land tax, the corporate land speculator can sit on land for a long time and flip it for significantly more, profiting from community-created value. And with no land tax, more investors will stop investing in productive things and instead park their money in land speculation, leading to underinvestment, declining infrastructure, and dangerous real estate bubbles.

The land tax is the return of the value of the land to the local community that made it valuable in the first place. It is a payment for benefits directly received in the form of proximity to a valuable community, local development, and government services.

The building tax, by contrast, is a straightforward disincentive to build and invest, a pure extraction of money from a productive activity we don’t want to discourage.

What about “if you want less of something, tax it?” Indeed, taxing buildings results in fewer buildings. That’s because somebody has to make buildings. By contrast, nobody makes land. That means that when we tax land, we don’t get less land, just less land speculation.

The land tax prevents the corporate land speculator from profiting on vacant or underutilized land and instead incentivizes the market to put the most desirable urban land to good use, encouraging development where it's most needed. Cities in Pennsylvania that shifted taxes off buildings and onto land saw significant increases in development and decreases in vacancy, providing powerful evidence for this effect.

But wouldn’t a land tax raise the price of land for new buyers? Counterintuitively, a land tax decreases the upfront purchase price. A savvy buyer calculates the present value of all future tax payments and subtracts that amount from the price they are willing to offer, and so the seller must accept a lower price because the buyer is taking on the ongoing tax obligation. In effect, the buyer pays less to the seller upfront and instead pays a portion of that value to the community over time through the land tax.

Throw Out the Bathwater, Not the Baby

DeSantis is right to focus on property taxes, and is a bold enough politician to swing for the fences. DeSantis has a chance to become a national leader in property tax reform that actually works by understanding the dual nature of property taxes.

If he does this right, he will not only align incentives for growth and prosperity, but also avoid a nasty showdown with local governments. There is much to learn from his Republican counterparts in Texas, who after loudly boasting about elimination, were forced to settle for limp half-measures that did nothing to address long term property tax reform.

DeSantis should eliminate the building tax, but keep the land tax.

This calculation assumes a conservative 5% discount rate. The Net Present Value in this case is similar to asking: how much money would I pay to the government today to not have to pay taxes on my building again?

Great article and points out a way to sell LVT politically: "We want to cut taxes on your buildings, (even if we want to maintain taxes on the land they are built on)"

Good explanation of the reasons to tax land. Return community-created value to the community that created it.