What Baltimore’s assessments taught me about cities, data, and fairness

The importance of land banks, how should we value commercial land, and more takeaways from months in the weeds on Baltimore's assessments

Lars and I spent several months studiously investigating Baltimore’s assessments, and our report we released was one finding from these investigations. Yet, the report does not capture many other discoveries and thoughts made along the way.

Without further ado, here are seven other takeaways from our investigation that feel important.

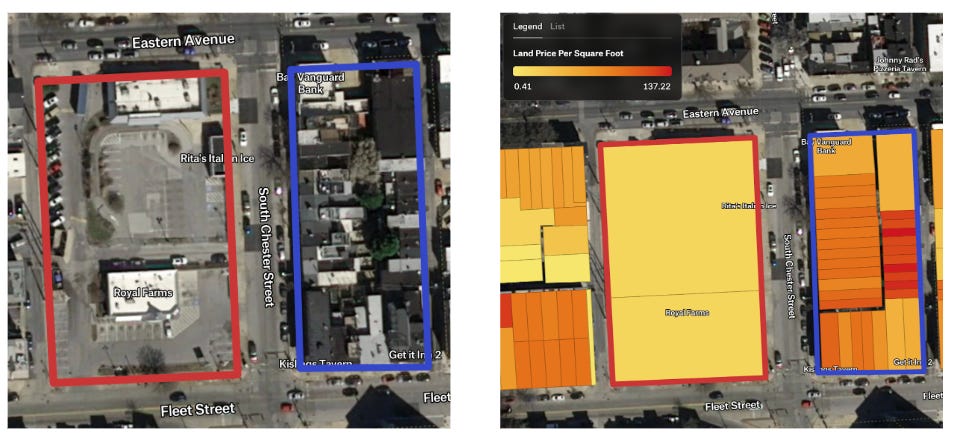

Commercial property valuations may undervalue land.

For commercial properties, assessment agencies typically rely on the income approach. This method estimates a property’s value based on its ability to generate income, often tied directly to financial statements.

The problem is that income-based assessments ignore parcel size. A business with no parking lot can end up with the same tax bill as a nearby business in the same location with identical financials but an enormous parking lot.

On one side of the street, a parcel dominated by surface parking is assessed at roughly $15 per square foot for its land. Directly across the street, a block packed with buildings and mixed uses is assessed at about $77 per square foot.

I compared the Royal Farms parcel, a small market located on a large lot, to a commercial building located catty-corner. Parking lot space accounts for 90% of the Royal Farms footprint, but only 50% of the building across the street, yet despite being a more efficient use of land, it pays nearly four times the property taxes per square foot.

The result is upside-down incentives: commercial assessments often punish efficient land use while rewarding speculation in the form of sprawling parking lots. And because the income approach is used widely, this problem extends beyond Baltimore.

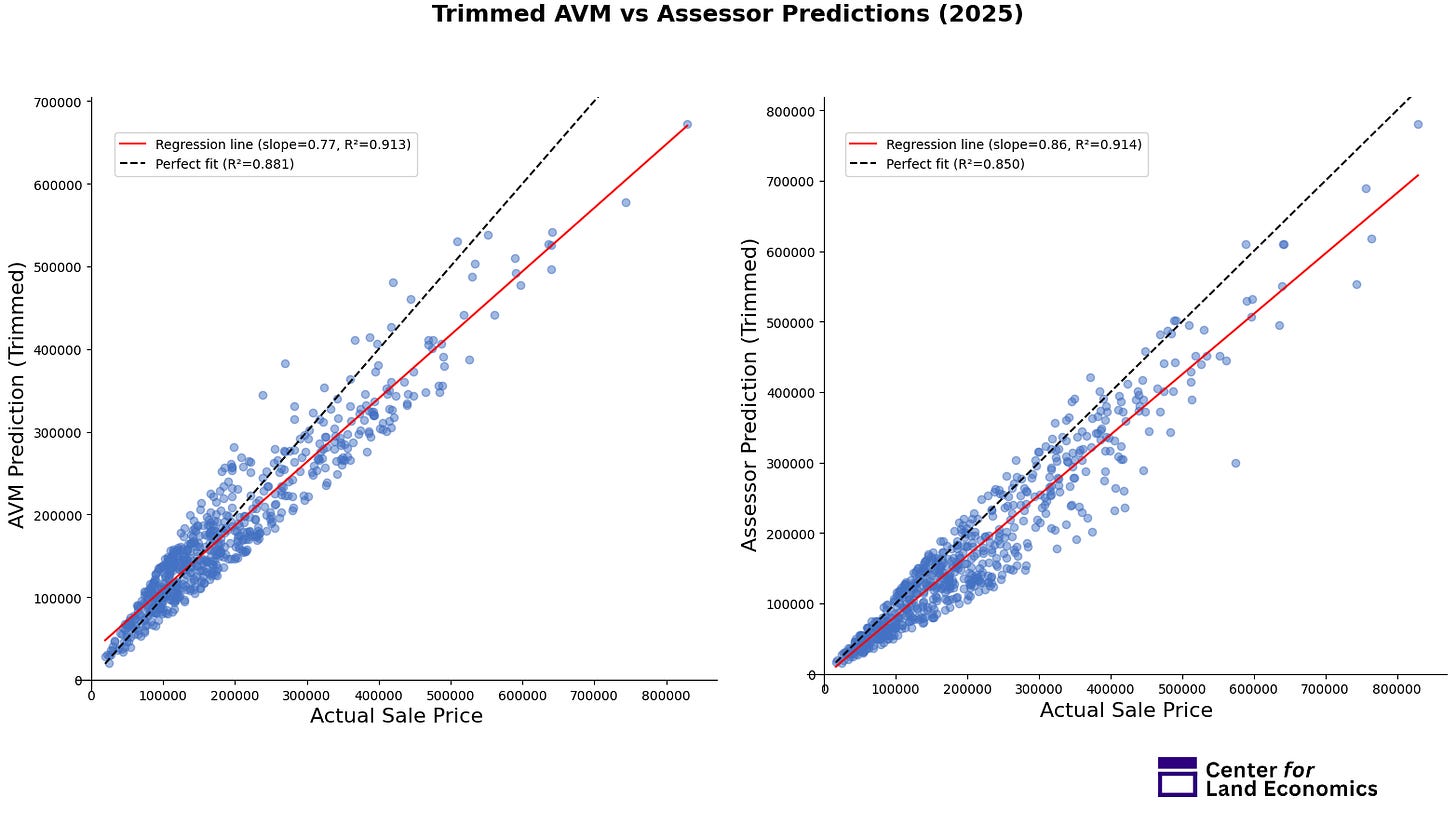

Our open-source AVM results for Baltimore are impressive considering Baltimore’s lacking data quality.

Toward the end of our report, we outlined many data quality issues in Baltimore data. These issues significantly hinder the automated valuation method (AVM) that Maryland currently uses in its assessment data. When we recreated an AVM using the Baltimore assessment data, we got poor results. With poor data on building condition and quality–two variables extremely important to AVM performance–and with missing data on some variables (eg. 40,000 parcels missing building square footage), Baltimore’s assessments must rely on a great deal of manual intervention. They should invest in improving their data quality and computer systems.

However, even with the lacking data, there is good news: enriching the data with public data sources can significantly help. So we did this with OpenAVMKit. After enriching the data with several public data sources, though still using the assessor’s shoddy building quality variable, our AVM performs impressively well when tested against sales data–competing with the assessors despite the poor data quality. Below are the charts that show the AVMs performance (left) against the assessor (right) on rowhome parcels. This exercise shows the promise of the combination of open-source data with open-source software, the capabilities of OpenAVMKit will only expand. The software was designed to be scalable across all jurisdictions.

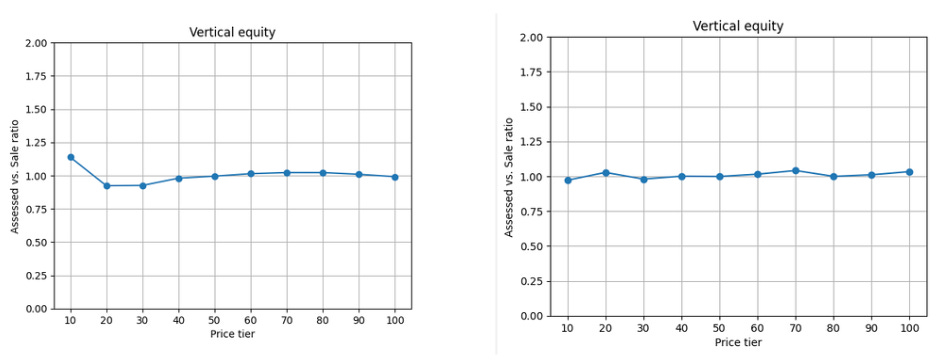

Vertical equity is hard to solve, and the problem is not immediately clear.

I had a strong bias when working with Lars on the OpenAVMKit: I wanted to solve the problem of overassessment of low-value properties. I kept trying to tweak and improve the model, but no matter how hard I tried, when it came time to run the vertical equity tests, the results always came back saying that the lowest valued parcels were consistently overassessed by our model: the problem of vertical equity in assessements.

Dr. Chris Berry at the University of Chicago has studied vertical equity across the United States and has found a consistent trend that low-value properties are overvalued and high-value properties are undervalued. My work on AVM’s now makes me believe there may be more to the story. While our AVM always seems to overassess low-value properties (to this point), there are two overarching reasons to possibly doubt the extent of the problem.

The first reason is there may be something unique in the nature of low value sales. One possibility, for instance, is that liens are taking down the sales price of properties. If a property is worth $40,000 but has a tax lien of $10,000, then it may only sell for $30,000, but an AVM would rightly list the full market value at $40,000. Therefore, sales data may be making vertical equity seem like a larger issue than it truly is.

The second reason is that overvaluation at the low end is almost baked into the math. Property values cannot fall below zero, so when models are trained on only positive sales, they can either get the value right or overshoot it. At the bottom of the market, that bias toward overshooting shows up as systematic overassessment.

I will also note that our data reveals parcel-level overassessment (”low-priced homes are over assessed”) but not neighborhood-level overassessment (”low-income neighborhoods are over assessed”). At the parcel level, in Guilford County, our AVM overassesses the lowest decile of property values by around 1.2x. However, when aggregating to the neighborhood level, the lowest valued neighborhoods do not see overassessment. There is a lot of nuance to parse out here that may be saved for another article, but because these tests are done against sales prices, this suggests that some of the perception of the vertical equity issue may be driven by parcels that are sold for anomalously low prices at the lower values.

I am not implying that AVMs and assessments do not have a regressivity problem, but the picture is more complicated than I first thought. More research will be needed.

Rental registries could unlock better assessments and serve the broader public good.

Assessments rely on sales data, but sales are not the only source of market data. Rent is, too–and perhaps with much more signal. While sales only occur every once in a while, rent is continuous.

The application of rents could be used to study a whole host of issues. Take the vertical equity issue described above. The issue may be caused by the nature of lower-valued sales, so instead of sales price, rent may be a better indicator of the true value of a property. With rental data, we could test the extent of vertical equity issues.

RealPage is a company that aggregates rents and helps multi-family apartment complexes price using algorithmic pricing. They are facing numerous lawsuits on account of price coordination. Widespread, well-maintained rental registries could serve as a “RealPage for the people”, and help fend off this type of coordination. Some cities have already begun implementing rental registries as others are considering the possibilities.

Many cities need better definitions of vacancy and better data on vacancy.

Baltimore struggles with vacancy. Vacant lots (land that has no improvement) and vacant structures (structures with no occupants). While officials have made addressing vacancy a priority, their efforts remain hampered by incomplete tracking systems. Current initiatives are focused on building a more accurate inventory of both vacant land and vacant buildings.

Baltimore is hardly alone. Philadelphia has also been battling the same issue, just look at this scathing headline in the Philadelphia Inquirer. I have heard from other city officials that they are concerned with their city’s ability to track vacancy.

Land banking and in-rem foreclosure are powerful tools for city governments.

Vacancy data matters because it enables cities to make real use of land banks. Land banks are parcels held by the public with flexible futures: they can be resold to private owners, preserved as parks, or directed toward nonprofit and community development. In effect, they are a way to bring idle land back into productive use.

Most land banks are supplied through in-rem foreclosure, the process by which properties with long-overdue taxes are transferred to public ownership. While the idea of government taking property can raise eyebrows, it is worth stressing that these are parcels long neglected, where owners have already failed their civic obligation to pay property tax.

I have spoken to city officials who are very worried about their capacity to support a land bank but who also recognize the promise. I expect we will see more cities adopting robust land bank programs over the next decade.

Still, there is a deeper question here: why do cities nearly always return this land back to private hands, effectively re-privatizing the land value? For Georgists, this points to an alternative path. Cities could retain land while ensuring its rental value flows back to the public. This is a much larger ask for cities who struggle enough to maintain their land bank, but it’s a thought worth considering.

Publicly-available data will continue to significantly increase and unlock new opportunities.

As part of the Baltimore AVM development, I used LLMs to parse hundreds of thousands of permits in Baltimore. I instructed the model to parse permits into one of four categories: minor renovation, medium renovation, major renovation, and complete demolition. The LLM did a great job. This structured data could then be used as inputs to the AVM and in the future may unlock lots of new analysis for urban studies.

There is open-source data everywhere. Overture provides AI to detect building geometries. ESRI provides an AI model to detect parking lots. Soon, more models will emerge to parse satellite imagery, planning documents, and other public records at scale. Then, open-sourced libraries like OpenAVMKit will only become more powerful.

More cities will shift their taxes to land value.

How is this one my takeaway from a report independent of LVT? Well, because this report was entirely separate from land value taxes–though driven by the same sentiment that land value matters–and yet, every single media piece that covered the report wanted to talk about LVT.

The appetite for land value taxes is growing, and the idea is no longer some fringe concept covered once every so often, but is weaving its way into policy conversations from high-level housing policy news to in-the-weeds reports of vacant land undervaluation.

Greg Miller is the Co-Director of the Center for Land Economics.

Great work, Greg. In my own writing on the logic of moving to land's rental value as public revenue, I make the argument that buildings are a depreciating asset requiring ongoing expenditures for maintenance. Then, every decade or so a building owner must put out a large expenditure for systems replacement. An annual tax on the depreciating value of a building imposes a heavy penalty on owners who are on a lower, fixed income. Also, if it makes sense to impose an annual tax on a person's most important depreciating asset, then the same flawed logic should apply to all depreciating assets -- to our automobiles, our computers, our televisions, our refrigerators, etc. etc. etc.

Hopefully, the work you are doing will result in the expanding recognition of "best practices."

Thanks for what you are doing.

Ed Dodson

Another reason why it might be "overvaluing" low value parcels is zoning/speculation.

Zoned capacity essentially creates a floor for every lot. The demand for high value lots essentially spills over and anything that has a SFH zoned capacity is equivalent, regardless of lot size.

So you don't get a continuous function all the way from the floor to zero.