The system of property taxation in the Lone Star state has been a fixture of its politics since it was ruled by Santa Anna. Lost among the causes of the Revolution my state’s students learn about in their 4th and 7th grade Texas history classes is the elimination of “a generous property tax exemption for settlers.” It is unacceptable that Texas, a state so defined by its sense of pride and exceptionalism, has in 186 years discovered no better answer to a question important enough to contribute to a revolution than endless bickering over adjustments to the margins. My state has never been a land of half-measures, and half-measured carve-outs will never solve the systemic problems that exist within Texas’ property tax system. What Texas needs is a total overhaul of the tax system.

Property tax administration in Texas has seen no shortage of notable reforms. Most recently, in 1979 and 1982. In 1979, the legislature attempted to “standardize the administration of local property taxes” by regulating the frequency of assessment, establishing qualifications for assessors, and creating “central appraisal districts.” In 1982, Texas did away with all “state property taxation.” In spite of these reforms, Texas’ property tax remains one of the highest in the nation and the property tax remains an indispensable source of state revenue, used to fund schools and emergency services as well as other essential government functions.

Problems with Property Tax

While it is local governments that administer and collect the tax, that hasn’t stopped voters from demanding statewide action. In 2022, Texans approved two amendments to the state constitution that will provide limited property tax relief. One amendment raises the homestead exemption, and another provides targeted relief to the elderly and disabled. These kinds of well-intentioned carve-outs may keep legislators in office, but they do little to address the real problems of property taxation. When Texans are saying that they want lower property taxes and increased funding for education, legislators should take that as a sign that there is a much more fundamental issue with how taxes are administered in Texas.

In an effort to address this fundamental dissatisfaction, the Texas GOP platform skewers the property tax as “the worst, most immoral method of taxation levied on Texans” and postulates that “no homeowner truly owns their property when that ownership is contingent on the payment of a tax.” Their plan for reducing property taxes is given to us in a few bullet points.

“ Fully remove the property tax.”

“The Legislature will choose the method to replace that funding but it must be approved by the voters.”

“This other method cannot be an income tax.”

This kind of messaging is nothing new to Texas Republicans, who have been officially calling for the abolition of property taxes for years. But it also stands in stark contrast to the proposals of Governor Abbott — whose property tax reform proposal is much more detailed, and much more modest, than what the Texas GOP has to offer. Abbott’s proposal is focused primarily on reforms that would reduce the financial burden imposed by property tax on families and municipalities. These include prohibiting “the legislature from imposing unfunded mandates on its political subdivisions” which require local governments to raise property taxes, and establishing a “property tax revenue growth cap of 2.5% per year.” Both of these reforms would slow the growth of property tax in Texas, but clearly, neither come close to satisfying a state party that sees property tax as an ethical catastrophe.

Allen West, chair of the state Republican Party, and Don Huffines, former State Senator, tried to capitalize on Governor Abbott’s non-compliance with the party line with concurrent primary challenges. Huffines, who made eliminating property tax a fixture of his campaign, said that Republicans needed to support a candidate that “believes in our party platform.” While Huffines and West failed to topple Abbott, they represent a bloc of motivated Republican voters who are not satisfied with the traditional edge-work approach to property taxes in Texas.

Representing the Texas Democratic Party, Beto O’Rourke promised to lower property taxes by closing “the tax loopholes that allow wealthy corporations to manipulate the appraisal process and shift … their tax burden onto the rest of us.” The loophole in question allows property owners to protest an appraisal by comparing their property’s valuation to the valuation of similar properties in a different area of the state. This kind of challenge reinforces inequality and ensures that property taxes are regressive, because even though this kind of challenge is available to all property owners, the cost of the legal proceedings necessary in order to utilize it only makes financial sense for large businesses and the very wealthy. Average property owners would end up footing the bill for those who can afford to file appraisal protests. Of course, the Beto campaign was right to point out the absurdity and inequity of this practice, but even they miss exactly how this kind of valuation challenge shifts the tax burden onto local communities. What these property owners are really doing, through a roundabout process, is lowering the portion of their tax burden that comes from the space their property occupies.

Both Republicans and Democrats recognize that there is something fundamentally wrong with the way the property tax system functions. Republicans are concerned about what property tax says on an ethical level about ownership, Democrats recognize how property taxes reinforce systemic inequality, and both are anxious about the fiscal future of Texas. Neither party has been clear-eyed enough to recognize that the problems with property tax stem from the way it inherently rewards waste and punishes productivity. Neither party has yet embraced the solution — replacing property tax with a land value tax.

The Way Forward

The land value tax is a tax assessed only on the value of the land itself, excluding any buildings or improvements on it. This means that builders, developers, business owners, and families would be free to improve their property as much as they want, without paying a cent more in taxes. It would no longer be necessary to fight the county assessor for every inch or compare buildings in Houston to buildings in Dallas to derive a valuation. This is because the land values of adjacent pieces of property are very similar.

Take, for example, Burnett Plaza, the tallest building in Fort Worth, and the parking lot catty-corner to it. The parking lot is on 1.05 acres of land compared to Burnett Plaza’s .82, and has a similar land valuation — $2,530,000 to Burnett Plaza’s $2,520,000. Two properties, that on their face couldn’t be more different, have roughly the same land value because they are similarly sized and situated within the same valuable part of Fort Worth. Under the current property tax framework, the owner of the parking lot would (if it were not owned by a church) pay significantly less in taxes than the owner of Burnett Plaza, because the improvement value of Burnett plaza is 1,918 times higher than that of the parking lot.

At first blush, this seems reasonable. After all, why shouldn’t the owner of the more expensive property pay more in taxes? However, this analysis punishes productivity and efficiency by focusing on what currently exists rather than what could exist. Both the parking lot and Burnett Plaza, by virtue of their existence, preclude the existence of something else that would otherwise be built in its place. A land value tax takes into account that there is a fixed amount of space that is suitable to build on. It asks landowners to pay, not for the contributions they have made to the local economy through their investment, but for the potential they eliminate by claiming exclusive rights to the land they own. Thus, where the property tax punishes the homeowner who builds an addition and the business owner who renovates their property, the land value tax encourages development and supports thriving communities.

Privately generated value should remain private, and value generated collectively should be used collectively. When we build houses, open businesses, or invest in infrastructure, we make our communities more attractive both for investment and for people looking for a place to call home. Through collective effort, we have raised the value of the land within our community. By making the value of the land the basis for taxation rather than income, consumption, or property, we ensure that this collectively generated value returns to the community, privately generated value remains in private hands, all the while aligning economic incentives against waste, neglect, abandonment, and mismanagement.

A land value tax would meet every requirement put forward by the Texas GOP in their platform. By eliminating the property tax and replacing it with a tax on the unimproved value of the land the property occupies, each Texas property owner would be able to say that the ownership of their capital investments is not contingent on the payment of a tax. Instead, property owners would only pay the annual rental value of the land they occupy as if it was completely empty and unimproved. In other words, you don’t continue to pay for what you’ve built. Additionally, this means that land speculation, buying and holding undeveloped valuable real estate for the purpose of selling it after infrastructure investment and private economic activity increase its value, would become unprofitable under a system of land value taxation.The end of this practice would be a relief to Texas homeowners as well as farmers and ranchers, who in part because of land speculation, are subject to soaring increases in property valuation, and therefore unbearable increases in tax liability.

Unfortunately, the proposals of Texas GOP insurgents like Huffines do not include land value taxation but instead revolve around replacing property tax with increased sales taxes. Sales taxes result in the poor paying a higher percentage of their income in tax than the rich because, contrary to some advocates of the sales tax, the sales tax does not become fairer because everyone can choose how they save or spend their money. This is because “low-income households spend a higher share of their budgets on basic needs, and … a smaller share of spending goes toward basic needs as a household’s income rises.”

Additionally, the convulsions within the Texas Republican party about the ethics of property taxation can’t be solved by a pivot to sales tax either. Just as soon as Huffines got his way, another group of disgruntled Texas Republicans would be asking why the government has any claim to their money just because they decided to spend it. Many of the justifications for sales tax, namely, that the government is entitled to a percentage of what you spend because they in some way facilitated the transaction, can be easily cross-applied to that perpetual boogeyman of Texas politics, the income tax. The only remedy for Texas Republicans who recognize that property taxes are philosophically unjust is to embrace the land value tax. A form of taxation that doesn’t punish you for being economically productive, for working and earning money, or for spending the money you earned.

Texas Democrats too, clearly see that there is something deeply wrong with the way our state collects taxes. Of all the loopholes and tricks people use to avoid paying taxes, the fact that the O’Rourke campaign singled out one that allows property owners to pay a lower tax rate on the value of the land they occupy as damaging to the community, shows the intuitive nature of the arguments for a land value tax. When the property tax system places excessive burdens are placed on low-income people and the value that is created through the economic activity of the community is privatized, displacement and the hollowing out of vibrant communities result.

The Pastoriza Plan

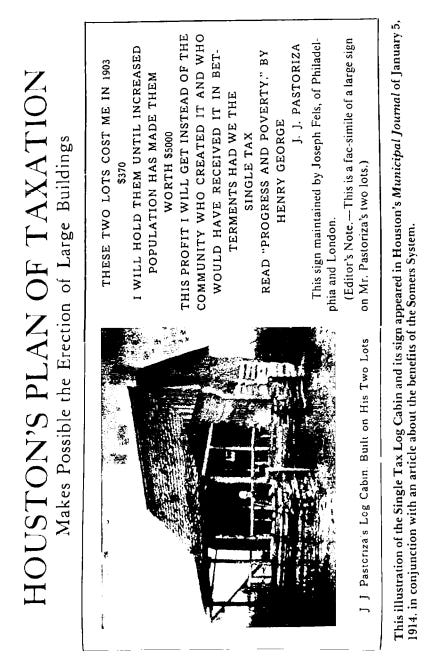

Democrats can look for inspiration within their own party history. A Texan named J.J. Pastoriza understood the potential of land value taxation more than 100 years ago. Pastoriza was a follower of the economist Henry George, whose work, Progress and Poverty, is the inspiration for the name of this publication, and the first hispanic mayor of the city of Houston. After a battle with the Texas court system, he tragically died in 1917 before he was able to see through his planned shift to land value taxes within the city of Houston. As it did for Pastoriza, the Texas constitution may present challenges for Texans in favor of land value taxation. Pastoriza’s plan, in an altered form, was able to survive “his six-year tenure as Tax Commissioner of the city” by accepting a less complete transition from property to land value taxation. These kinds of compromises may in the short term be politically or legally necessary, but with a constitution that has been amended 517 times since 1876, Texans should be confident that any challenge can be overcome.

The systematic expropriation of both publicly and privately generated value cannot be allowed to continue. At the same time, any shift in tax policy must come with an assurance that the government will still be solvent after the transition is completed. Fortunately, land value taxation is flexible and backed by leading economists. Split-rate taxation, the practice of taxing land values and property values at different rates, is an excellent way to test or phase in land value tax over time. By charging a higher rate for land than for property, we can still capture many of the effects of a full-scale land value tax system, at a smaller scale, without full implementation. By shifting the tax burden from property to land through a split-rate system over time, any move towards land value tax can be made to be revenue neutral. Crucially, there is significant support across economics for a shift to land value taxes, allowing for bipartisan cooperation. Milton Freidman and Joseph Stiglitz, two Nobel laureates often perceived as occupying opposite ends of the political spectrum, agree that land value taxation is an improvement. Friedman called it the “least bad tax” while Stiglitz argued that “a tax on the return to land, and even more so, on the capital gains from land, would reduce inequality and, by encouraging more investment into real capital, actually enhance growth.”

More than perhaps any other state, Texans have a unique connection to the land we live on. From the days of Spain, Mexico, and Stephen F. Austin, to the ranchers, cowboys, and oil fields, Texas was built on the value of its land. Even our state capitol building, made of Texas red granite, was financed not through taxes, but through the sale of a large tract of land in the Texas Panhandle. Property taxes, and the attitude of our politicians towards them — tending toward half-measures and reaction rather than systemic change, have strained this connection. Property tax has led to exploding tax liability for Texans by incentivizing land speculation and tax avoidance. Because of property tax, we stretch communities of renters, homeowners, and entrepreneurs to the limit, and facilitate the transfer of wealth from the productive to the speculator. In the next legislative session, when Texas politicians gather to discuss how to solve the problems posed by property taxes, it would serve them well to recognize that the problems with property tax are intrinsic to the system. The solution is to move away from property taxes entirely, and instead tax land.

I have found over the past 50 years of membership to the Georgists IU that little progress has been made in the Single Tax proposal. I there choose to introduce an alternative way of doing the same thing WHICH WILL NOT CAUSE OPPOSITION FROM LAND OWNERS.

A MORE STEALTHY GEORGIST CAT

The Georgist cat is small and lean

And often doesn’t get to be seen.

It hides in the branches of an economic’s-tree

So it takes a long while for you or for me,

To appreciate its cute and original form

That the landlords are so ready to scorn.

The economic’s-tree has many fine branches

(On which we contend, there are no free-lunches).

Whilst the land-owning rich in the city all claim

As bloated capitalists, that they’re not to blame

For the gap that lays ‘twixt the poor and the wealthy,

But oppose any tax to make our nation healthy.

Have you heard the tale of a committee, that

Thought to bell and get warning of a fat cat?

But could not find a soul to apply this device,

Because typically all were a council of mice!

Our Georgist cat has a bell ready-fitted,

(Which makes this analogy more to be pitted).

This warning sound makes our ideals unwanted,

For a new tax is how politicians get doubted.

So the Georgist cat fails to catch any mice

That pose as landlords, along with their vice.

But how shall we silence the bell’s warning sound

And quieten the news that our pussy’s around?

Our Georgist feline is in serious error,

‘Cause its bell draws attention not only to whether

Valuable sites can be ethically shared,

But also the rent from a site is declared

As the means to replace other kinds of taxation,

Which obviously causes the landlords vexation.

In the economic’s tree many other beasts lurk

But are missed, after learning of Henry G’s quirk

Through the cat-finder’s recently brilliant discovery.

This writer seeks a new means for recovery

From our politi-unacceptable claim,

And stealthily project LVT once again.

If we would but examine some more of the tree

Alternatives are waiting there for us to see.

Among them is hiding a far better way

For an equivalent LVT effect, to stay

In essence, without causing such evil offences

To the landlords and their partitioning fences.

When a property-owner decides to sell--quick

The gov’ment buys its land, and not the public!

Its occupant then leases it for a similar fee

To the One-Tax of Henry George’s decree.

Any buildings on-site should be sold as previously

But without the land, on which the price grievously

Had risen, with huge speculation in its advance

That stopped entrepreneurs from having a chance.

The cost of this land must be raised through new bonds

Which the government sells and the public responds,

‘Though their interest-rate’s a bit lower than rent,

Their returns are more stable than the average tenant!

This process will take many years to complete--

So its financial support is no great money feat.

After the lease-fees begin to collect,

Gov’ments can tax less, and firmly expect

To pursue this policy without change, until

All the lease-fees are site-rents in the Gov’ment’s till.

With the land properly shared, the government sees

That site development stays with the current leasees.

Other taxes that cause so much trouble and hate

Are scrapped, with great pleasure to all in the state,

Except for some bankers and the tax collectors

Whose actions no longer apply in these sectors.

Land-rights will be shared through this simple device,

By a fast-growing country that takes our advice.

How do you feel about adding an exemption for primary residences? This is typically the little detail that gets my disinterested relatives onboard, because it shifts them away from thinking about themselves (taxes are scary!) to thinking about commercial real estate. But I don't have a good sense on the impact such an exemption would have. For example, is that a 10% ding to tax revenue? 90%? Does it create perverse incentives I haven't thought of?