New Reports: Land Value Taxes in College Towns

Case studies from South Bend and Princeton examine the impact of shifting taxes from buildings to land. The shift would drive development, promote equity, and capture community value.

In the past month, the Center for Land Economics (CLE) and Progress and Poverty Institute (PPI) published reports on implementation of land value taxes in two college cities: South Bend, Indiana and Princeton, New Jersey. The evidence is strong: land value taxes are a good policy for these cities.

South Bend

Greg here–I worked with Notre Dame’s Student Policy Network (SPN) to analyze the impacts of implementing split-rate tax in the City of South Bend, IN. The data presented here is a combination of the efforts of CLE and SPN, and the final report and presentation from the students can be found here.

South Bend is a modest but mighty city. Once propelled by industry, primarily with the presence of Studebaker, the city experienced a post-industrial population decline from the 1960 until 2010. However, in the past decade, South Bend has proven itself as a rebounding city with development occurring. I, for one, am a big fan of South Bend, not just because I am a Notre Dame alum, but because I have watched the city improve significantly over the past seven years–since I first arrived in 2018.

South Bend has two unique characteristics that make a shift to land value taxes a strong policy in the area. First, as a rebounding post-industrial city, South Bend has plenty of vacant and underutilized land. Second, with the presence of the University of Notre Dame, there is an expanding radius of high-value land around the university campus which the city may want to capture.

Our study confirms that LVT would accelerate South Bend’s rebound. The following results model land being taxed at four times the rate as buildings while holding revenues neutral, and the results are focused on the directional impacts of a shift in taxes off of buildings and onto land.

1. LVT shifts burden from productive uses of land to vacant and underutilized property.

Property owners sitting on empty lots would feel the impact of LVT most directly. Our analysis shows that vacant land would face a 127% tax increase, while parking lots would see taxes jump by 96%. This isn't just a statistical finding – it represents the core function of land value taxation at work. By significantly increasing carrying costs on undeveloped land, LVT creates real market pressure to build housing, commercial spaces, or other productive uses rather than speculating on future appreciation.

Meanwhile, every other property type sees a median decrease in taxes, other than food and hospitality. This means a split-rate tax shifts the tax burden from residential and commercial land to vacant and underutilized land. At the same time, owners of vacant land that choose to develop will no longer be disincentivized to develop by higher property taxes. For South Bend, a city with numerous vacant parcels in its urban core, this could accelerate the ongoing revitalization efforts without requiring new public subsidies.

2. The tax shift is progressive.

LVT addresses economic inequality. Our data reveals that as neighborhood incomes rise, so does the increase in tax responsibility under a shift towards LVT. Lower-income census blocks predominantly show tax reductions (falling below the red dotted line), while higher-income areas show increases. The upward-sloping trend line confirms that land value taxes naturally produce progressive outcomes without complex exemptions or carve-outs. In South Bend's case, LVT would provide meaningful tax relief to working-class neighborhoods while asking more from those with greater means, creating a more equitable property tax structure.

3. The tax shift captures increasing land value near Notre Dame.

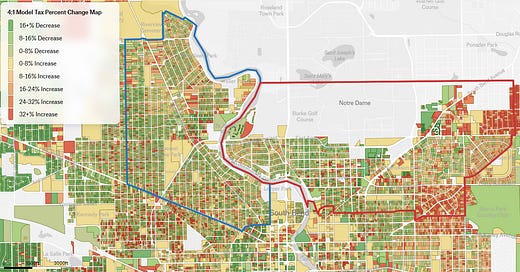

Universities create immense value in their surrounding communities, but much of this benefit gets captured by private landowners rather than the public. Our analysis reveals how LVT can help South Bend reclaim some of this community-generated value. The heat map clearly shows concentrated areas of tax increases (in red) around Notre Dame's campus, where land values are significantly higher due to proximity to the university. The area further from campus is indicated in blue and has many parcels decreasing in tax under the split-rate system.

When examining developed properties near campus, we found they would experience a 7% tax increase under the 4:1 split-rate system, more than three times the increase for comparable properties in the area further from campus (2%). This difference highlights how effectively LVT targets land that derives its value from community investments and amenities. When including vacant parcels in this analysis, the overall tax change appears similar between campus-adjacent areas (13%) and the further region (14%), but this is due to the higher amount of vacant land in the area further from campus. By implementing LVT, South Bend could ensure that those benefiting most from Notre Dame's presence contribute proportionally to public services that make the entire community thrive.

4. The tax shift decreases taxes on rental properties.

Housing affordability stands as one of South Bend's most pressing challenges, and our analysis shows that LVT offers unexpected benefits for the rental market. The data reveals a contrast between how owner-occupied homes and rental properties would fare under the proposed 4:1 split-rate system.

The median single-family house decreases 5% under the tax shift, but these effects can be separated by owner-occupied (homestead) properties and rental properties. While homestead properties show mixed results—with 47% seeing decreases (essentially a coin flip) and an average modest increase of 4%—non-homestead properties experience dramatic relief. An overwhelming 84% of non-homestead properties would see tax decreases, with an average reduction of 11%. The decreased taxes on renter-occupied homes would ease rent increases over time.

The caveat: circuit breakers.

South Bend could theoretically implement a universal building exemption (effectively a land value tax) with approval from the state. However, under state law, property taxes are capped at percentages of total assessed value: 1% for homesteads, 2% for other residential and agricultural property, and 3% for all other properties. The catch? A remarkable 92% of South Bend parcels already hit these caps. This means most property owners currently receive automatic refunds for any taxes assessed above their circuit breaker limits, essentially negating the impact of most tax structure changes. Therefore, South Bend would have to ask the state to also get rid of circuit breakers–a large ask.

However, property tax increases passed through referendum do not get impacted circuit breakers. South Bend School Corporation recently passed a 0.33 millage rate via referendum. The state could have authorized that to be a land tax rather than a property tax.

Princeton

Steve conducts research on LVT at the Progress & Poverty Institute, a non-profit based in Princeton NJ. One of America’s earliest colonial townships, Princeton saw George Washington score a decisive victory in the early days of the Revolutionary War. Princeton University and the Institute for Advanced Study are the lifeblood of the township, having hosted influential thinkers like James Madison, Albert Einstein, Toni Morrison and Sonia Sotomayor. Today, Princeton is known for its intellectual institutions and colonial charm, albeit with house prices averaging over a million dollars.

We wanted to understand how a LVT shift would impact our local community, so we analyzed the effects of splitting the township’s municipal tax rate (of $0.58 per $100 of total property value) into a tax of $0.86 per $100 of land value, which enables taxes on buildings to be halved to $0.29 per $100 of improvement value, leaving overall revenues unchanged. Results are summarized below, but a full report is available here.

1. LVT is a Density Discount

Reflecting the way that LVT rewards productive land use, apartments enjoy a municipal tax cut of -20% on average, from just under $16,000 per year to just under $13,000. Commercial properties also tend to benefit, enjoying a -6% decline in their municipal tax bill on average. As expected, the LVT shift penalizes underutilized land, raising tax bills on vacant land by nearly +50%.

Effects on single family homes are mixed, with annual tax bills increasing by +$40, or +1% on average. However, this masks a wide range of effects, with 2,411 homes seeing their taxes fall (typically by around -10%), and 4,724 seeing their taxes increase (often by +10% to +25%). As a general rule-of-thumb, homeowners whose house is worth more than half of their total property value will enjoy a tax cut, whereas those for whom land is the majority of property value will see their taxes rise. This demonstrates the way in which an LVT shift rewards productive land use.

Readers who are interested in exploring the effects on specific properties may enjoy exploring this interactive map. Properties in blue enjoy a tax cut, whereas properties in red see their taxes increase under an LVT. Properties can be filtered by zoning type using the drop-down menu on the left. Details for individual properties can be viewed by clicking on them.

2. Sample Properties

To bring these results into the real-world, we demonstrate how tax bills would change for three sample properties: the Albert Einstein House; a site ripe for redevelopment; and a vacant lot.

Einstein lived in the charming house at 112 Mercer Street for twenty years while conducting research at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study. This property is currently valued at $1.4 million which is split pretty close to 40:60 between land and buildings. By the rule-of-thumb introduced above, we can expect that this will mean that the Einstein House enjoys a tax cut under an LVT shift. Indeed, our proposed LVT will see this house’s tax bill fall from $8,240 to $7,530, a tax cut of -6%.

By contrast, 21 Wiggins Street is one-third of an acre of prime real estate, located right in the heart of Princeton, and with only a couple of small existing buildings. Permits were obtained in 2021 to redevelop the site into a four-story building with 19 apartments, however; construction is yet to begin. The site, valued at $1.9 million due to its redevelopment potential, has existing buildings that comprise only 12% of the total property value. This relatively low-productivity land use is penalized by the shift to a land value tax, which would result in taxes rising from $11,130 to $15,290 under our proposal. This increase of $4,160 (+37%) is the largest dollar increase for any single property in our data.

Lastly, there is two-thirds of an acre of vacant land nestled right between suburban homes at 532 Princeton-Kingston Road. This property has been owned by a development corporation since at least 2007 and has sat vacant and overgrown the entire time. This parcel was given an assessed value of $364,000 last year (a considerable underestimate, if you ask me), which was understandably attributed entirely to land value. This results in this lot seeing its taxes rise by +49% under our proposed LVT shift, from $2,100 to $3,130.

Here we can clearly see the way in which a shift towards land value taxes rewards properties which are built-out and well-maintained, incentivizes the redevelopment of underutilized sites, and penalizes speculative ownership of vacant land.

The evidence from South Bend and Princeton is compelling. These reports demonstrate that shifting taxes off of buildings and onto land can unlock the potential of underutilized properties. The shift, however, is even more powerful than current-day tax burden shifts. By reducing taxes on buildings, development will accelerate and create thriving cities.

If you work in a city that is particularly prime for a land value shift, reach out: greg@landeconomics.org.

Very interesting analysis.

One thing I notice is that agricultural land experienced a very large increase in taxes in Princeton. This is troubling to me, particularly if LVT were implemented in an entire state.

Do you think that a state-wide LVT would experience similar changes in tax rates for agricultural land, or is this just because this study was only for smaller cities?

The issue with farmland could be largely resolved if the farms (assuming they have the potential to be productive in the long run) are placed under a conservation easement, eliminating speculative value. This is sound policy if you want to maintain a local food system and the other open space values of farmland