Life at the Margin of Production

How land rent drives poverty and inequality in the modern world

The key to understanding the tremendous levels of inequality and deprivation that we see today, despite the immense power of modern technological advancement, is the law of rent and the corresponding law of wages. Once one fully grasps these simple economic laws, both the cause of and the solution to poverty in the midst of plenty becomes obvious. How then can we demonstrate the law of rent and the law of wages in our modern, highly urbanised and technologically sophisticated societies?

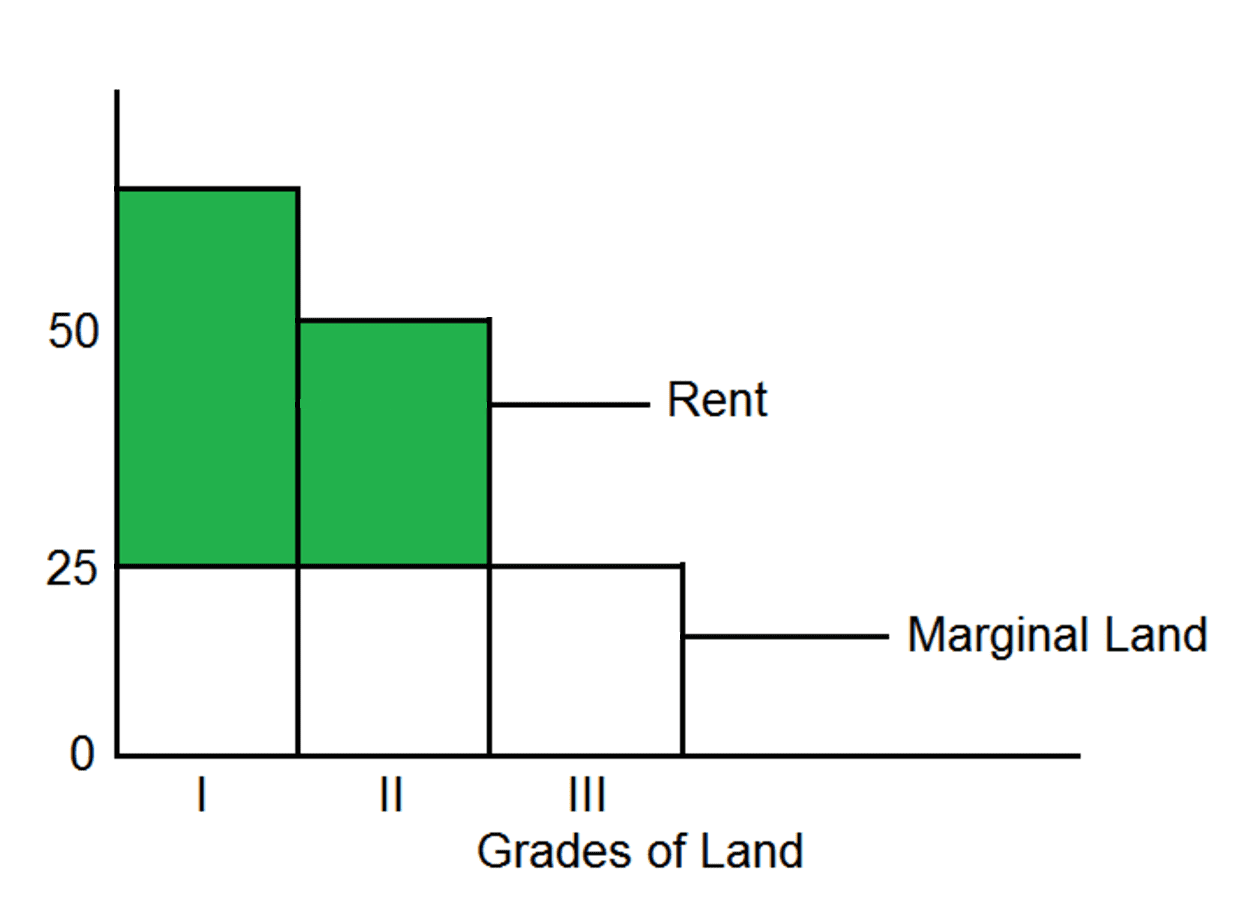

To begin with, it makes sense to quickly define the terms, lay out the broad structure of the law of rent and cite modern, tangible, real-world examples as we go. Agricultural production was what inspired David Ricardo to originally create the Law of Rent in his book On the Principles of Political Economy in Taxation. His classic example of the margin of production is “the productive capacity of the next available plot of rent-free land”. We know that some parcels of land are better for growing crops than other parcels. Where the best land is freely available to whoever will claim it, we can think of all the produce – the wheat or the fruit or the rice or whatever the case may be – as wages. Some people will work harder or smarter and, thus, be rewarded with better wages, but no one would be rewarded simply for owning the best land.

That is where rent comes in. Rent is the return for land ownership, and it is determined by the margin of cultivation. If the best land – capable of yielding, say, ten bushels of wheat – is taken and the only parcels freely available yield only seven bushels of wheat, then the landowner can offer a wage equivalent to seven bushels and receive ten bushels in return, he needn’t offer a higher wage – since no one could earn more than that by spurning him and working for themselves – but he cannot offer a lower wage since no one would choose to make less money working for someone else than they could earn by working for themselves. The difference, equivalent to three bushels of wheat, is the rent.

This phenomenon is easiest to observe in the early phases of colonial development:

“Every colonist gets more land than he can possibly cultivate. He has no rent and scarce any taxes to pay. He is eager, therefore, to collect labourers from every quarter and to pay them the most liberal wages. But these liberal wages, joined to the plenty and cheapness of land, soon make these labourers leave him, in order to become landlords themselves, and to reward with equal liberality other labourers who soon leave them for the same reason they left their first masters.” Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations

These dynamics remain the same even in modern, urbanised, industrial societies. Instead of the suitability of each parcel of land for the growing of particular crops, the value of land in a city arises, most commonly, from its location. Businesses will pay far more money for a site on a high street, with plenty of foot traffic, or a site right next to a well travelled highway, compared to a site in some out-of-the-way corner, even if the quality of the physical land in either case is identical. For workers, very similar considerations are made in the choice of dwelling. Just as commercial enterprises want sites close by to lots of customers, and industrial concerns want to site their factories near centres of population, workers want to situate themselves close to good jobs, public transit, and social amenities.

In this case, the margin of production is mostly visibly expressed in the throwing up of great swathes of makeshift dwellings on the outskirts of growing cities in the developing world.

The slums around Jakarta illustrate very well that people will face much hardship for access to the wealth generated by the growing cities of the world.

Those who are not able to pay the exorbitant rents in big cities with large job markets, will migrate to unoccupied land and throw up rudimentary housing structures of their own. When the issue of housing is divorced from the margin of production, however, a far more comprehensive picture emerges.

The periphery of a highly productive urban core is not always a sore sight, nor does it always imply a life of meagre subsistence. Just as the margin of production can be lowered, as all the best land is gobbled up and the landless are forced either to surrender a large part of their wages to their landlord or else be driven onto undesirable and unproductive land, the margin of production can be raised by the progressive march of technology.

This is the story of the suburbs, as we know them, today. With significant levels of government investment in highways and access to loans with which to purchase a suburban dwelling, an entire class of people can travel into the city within an hour, covering a distance that would’ve taken their ancestors half a day on foot. It is here, however, where we see the striking influence of the law on the margin of production.

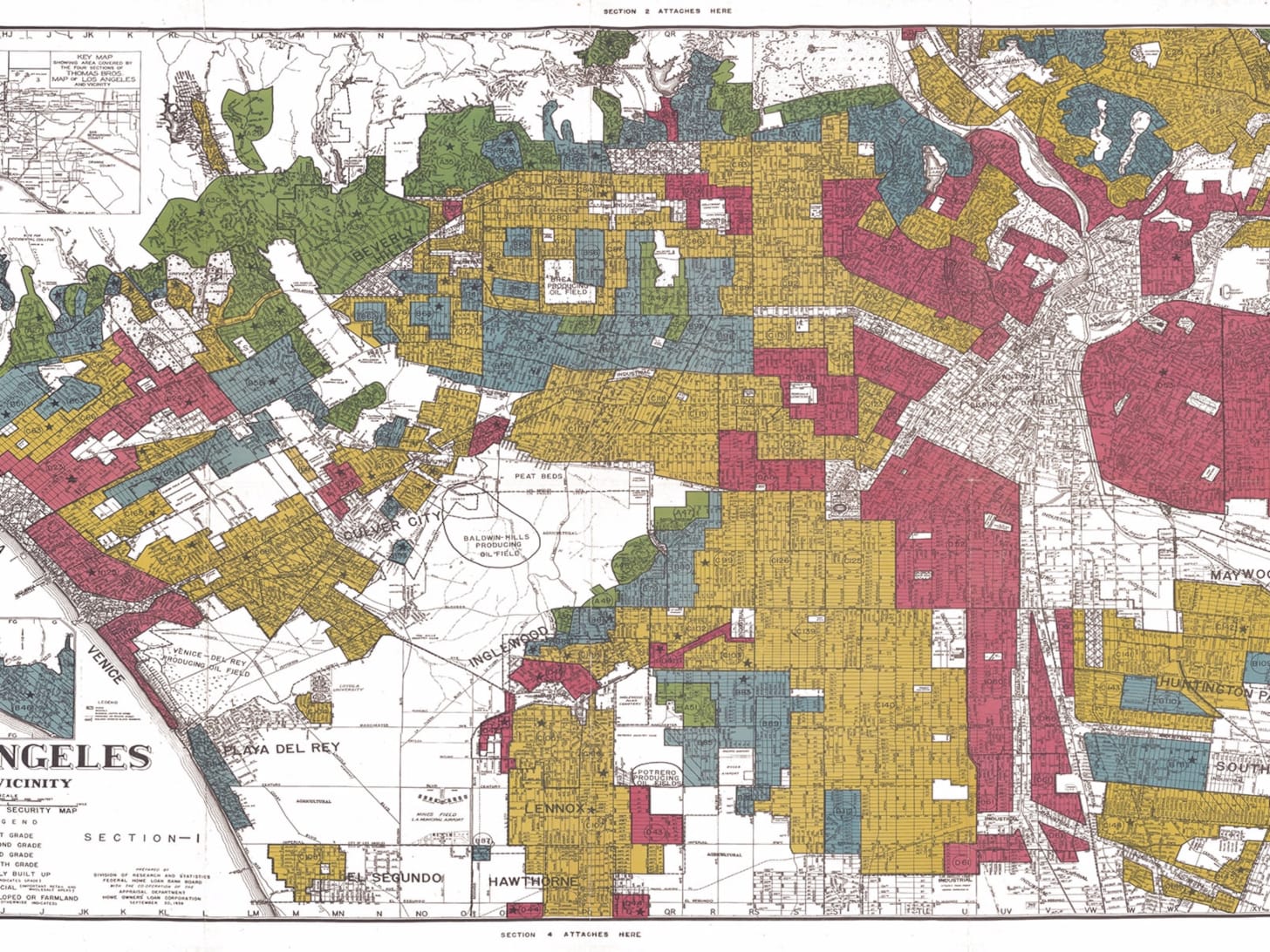

The story of the suburbs is not just the story of highways and automobiles pushing the margin of production miles and miles further away from the urban core. It is also the story of white picket fences, single family homes with large yards and plenty of space from one’s neighbours. It is easier for some people to believe that there are simple natural patterns of development. In fact, they are conscious legal creations, designed to ensure that the benefits of any shift in the margin of production are not shared evenly.

The story should be familiar to anyone possessing a basic understanding of twentieth century American history, subsidised mortgages and other financial benefits, which generally excluded ethnic minorities, allowed whites to leave the inner cities and replicate social and economic patterns of racial segregation which were otherwise illegal.

“From 1933 to 1954, the HOLC in effect barred African-Americans from buying homes in attractive neighbourhoods even when they could afford them. Suburban housing was also expanded almost exclusively for whites, for example in developments largely funded by mortgages from the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), another New Deal agency that enabled racial segregation. The HOLC and FDA’s practices reduced home prices in mostly black neighbourhoods, while keeping non-whites from leaving them. In the 1950s Dwight Eisenhower’s federal expansion of highways through most American cities also physically cut off minority-heavy neighbourhoods from whiter areas of cities. This ensured that urban segregation outlasted the era when discriminatory policies were deliberately pursued.” – The Economist

The relationship between surbuban land and the law of rent might be hard to decipher. In the classical example, we have the owner of land extracting rent and offering wages. Here, however, the wages are offered by the owners of land in the city – indeed, commercial and industrial uses of land are often severely legally restricted in the suburbs – and the rents come from the proximate location to these jobs, since the invention of the automobile and government creation of roads negates what would otherwise be an excessively long distance. A remarkable example of life at the margin of production emerges, then, when we observe workers taking advantage of a commute even though they are unable to afford to rent a location either in the city or the suburbs.

With the invention and popularisation of “mobility-as-a-service” apps, where workers were able to be hired as couriers and chauffeurs on-demand, some of these workers would drive into the city and live in their cars.

“Every Saturday morning before the sun rises, 35-year-old Uber driver Sultan Arifi rolls up the sleeping bag in the front seat of his car, places it in the trunk, and prepares for another day of work.

He will spend the next 12 hours picking up as many passengers as he can on the streets of San Francisco before returning to a grocery store parking lot in the north of the city to sleep, often for six hours or less, rising as early as he can on Sunday to do it all again.

The 35-year-old immigrant from Afghanistan commutes into San Francisco from Modesto, some 80 miles away, where he lives in an apartment with his wife and four children. He is one of a growing group of Uber drivers in San Francisco who spend nights in their cars in parking lots across the Bay Area on the weekends. Some come from places as far as eight hours away to make a living before returning home.” – The Guardian

Whilst this story might seem novel, there have always been groups of people living on the road throughout human history. In some cases, we can trace the lives of communities living on marginal land to the present day. In Europe, perhaps the most visible of these communities are the continent’s various nomadic groups, such as the Romani and the Irish Travellers. In Britain and Ireland, the government has provisioned these groups with what are called “halting sites”, land designated for their use. Where halting sites are not provided – and in many places they are fiercely protested and plans for them are legally defeated – conflicts arise when nomadic groups seek to use vacant land without permission.

“Despite the widespread and continuing closure of traditional stopping places, enough common land had survived the centuries of enclosure to provide enough lawful stopping places for people whose way of life was or had become nomadic. But in 1960, the Caravan Sites and Control of Development Act gave local authorities the power to close the commons and other traditional camping places to Travellers, which many proceeded to do with great energy. After a wide-ranging campaign of resistance to evictions, a new Caravan Sites Act was passed in 1968, ordering local authorities to provide sites for all Gypsies residing in or resorting to their areas. For the first time in 500 years, the British state had recognised its responsibility to provide secure, legal stopping places for British Gypsies. Few non-Gypsies have ever visited an official Gypsy site. Many epitomise the definition of a ghetto – a racially segregated and enclosed settlement. Many have been built near rubbish dumps, sewer works or noisy industrial facilities. In 1994, the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act removed the legal obligation to provide even these sites. As a result, some local councils have privatised and closed many of the legal stopping places available to Britain’s travelling population. Government policy currently recommends that travellers should house themselves, but Gypsy families that attempt to live on their own land are often denied planning permission.” – Travellers Times

Opposition to marginalised groups having access even to idle land does not just find expression in conflicts between settled and itinerant populations, however. Nowhere is the importance of location value – the main source of rent in urban economies – more obvious than within the subject of social housing. Whilst it is commonly framed as an issue of shelter, we all implicitly understand that for people to thrive they need more than just a roof over their head and a tap with running water. People need access to wages which, in economic terms, means they need access to valuable land.

In the United States, this is reflected in the history of public housing projects. In Chicago, for example, the expansion of public housing for the city’s poorest faced extreme racist opposition.

In 1953, when a black woman and her family moved into the Trumbull Park Homes public housing project, it sparked a violent reaction from its white residents which lasted weeks and was reignited after the introduction of another ten black families later that year. Racism ensured that public housing projects in Chicago generally conformed to the racially segregated settlement patterns that had previously developed. This, in addition to other factors – including a federal government increasingly obsessed with cutting costs – resulted in projects that are now regarded as failures.

In economic terms, this fierce opposition to allowing more people into one’s neighbourhoods or cities or suburbs – even if equally or primarily motivated by bigotry – is called rent-seeking.

In the suburbs, this means that an expanding job market in the city must be turned into higher prices for single family homes rather than higher density dwellings that allow newcomers to share the rent burden. Even in public housing, as mentioned above, rewards must be reaped entirely by existing residents. Rent can be invisible in some cases and starkly visible in others.

Rent can be captured by numerous entities. The private landlord is the obvious example, turning rent into passive income, but homeowners capture rent in the form not only of opportunities afforded to them by the location value of their property (this is called imputed rent, and has, at times, being taxed just like private rental income) but a higher sale price when they eventually decide to move away. The state can also capture the rent, in the form of increased tax revenue and income from tenants in public housing. Even tenants themselves can capture rent, through devices such as “rent control”, the difference between the real rental value of land and the price actually paid represents location value successfully captured by tenants.

Understanding this is the key to realising how otherwise dramatically different situations are all related to the private capture of rent by the landed. African Americans driven out of white communities by violence, nomadic groups in European restricted to the least desirable land, hard-working immigrants forced to sleep in their cars to make ends meet, and the great masses of humanity consigned to life in slums in the developing world are all groups defined by the margin of production.

There are two factors at work here, responsible for considerable hardship and suffering. The first is quite obvious, rent, despite being created by broader society in the form of technological progress, government investment and the labour of working people, is privately captured by landowners. Sharing the rent would fairly compensate the landless for the impositions – both legal and economic – of the landed.

“The productive powers that density of population has attached to this land are equivalent to the multiplication of its original fertility by the hundredfold and the thousandfold. And rent, which measures the difference between this added productiveness and that of the least productive land in use, has increased accordingly. Our settler, or whoever has succeeded to his right to the land, is now a millionaire. Like another Rip Van Winkle, he may have lain down and slept; still he is rich-not from anything he has done, but from the increase of population. There are lots from which for every foot of frontage the owner may draw more than an average mechanic can earn; there are lots that will sell for more than would suffice to pave them with gold. In the principal streets are towering buildings, of granite, marble, iron, and plate glass, finished in the most expensive style, replete with every convenience. Yet they are not worth as much as the land upon which they rest-the same land, in nothing changed, which when our first settler came upon it had no value at all.” – Henry George, Progress and Poverty

The second factor can be a little harder to see. In a classical demonstration of the law of rent, the addition of land to the general economy comes in the form of a settler taking up residence in less desirable land. In the real world, however, land does not have to occupied to be claimed, so that even in the great hustling and bustling high-rise metropolises, one can encounter sites composed of bare concrete, serving no other purpose than to enrich the owner by massive increases over their original value when it comes time to eventually sell up. In this way, the margin of production is kept low even where there is highly valuable land yet to be added to the economy.

It would likely seem perverse to most people if a business owner who kept good wages and earned a fine profit were to fire all of his workers and close his factory’s doors, adding to the problems of unemployment and destitution in his city. In effect, this is what the owner of a vacant lot is doing, if only in a more passive way. Examples abound, catalogued in valuable resources such as Vacant Land NYC, of vacant lots and other underutilised land such as surface parking lots even in the heart of the most desirable and productive places in the world, with astronomical rents that fall exclusively upon working people.

Confiscating the ground rent, even before the question of redistributing it for the common good is even considered, would drive the margin of production higher as landowners would be forced to put their land to its best use.

There is another positive consequence of drawing the margin of production inwards, unlocking all the empty lots and sites currently being used inefficiently. Rents on the outlying land would fall, opening their use up to those people that have always preferred life on marginal land, whether out of personal or cultural habit.

“As labour and capital migrate in the process of maximizing their efforts on the best land, the demand and the value of the least productive land will fall. Soon, within 50 or 100 miles of every city, there would probably be land without value. It would be good for building houses or growing crops. It might even support some small business, but other land would be so superior, so much more in demand, that it would have no rental value at all. It could be used without the payment of rent. Having free land available to everyone to live and work on would deliver high wages for everyone — just as it did in past centuries when America had a free land frontier.” – Mike Curtis

The difference between the landless and the landed is the private capture of the ground rent of society and Georgism holds the key to eliminating the tremendous inequalities foisted upon the landless poor, by taxing away the value of land and equitably redistributing it.

It might be helpful to explain that rent exists whether land is owned privately, owned publicly or is not claimed by anyone. Rent can be described as that portion of whatever tangible wealth is capable of being produced at a given location attributable to the characteristics of the location and not by the quality of labor or capital goods employed. In general, people tend to claim the potentially most productive locations first; then, when all such locations are claimed will (again, generally) begin to claim the next potentially most productive locations. [Ed Dodson]

Unfortunately the land owners will never see the ethics nor agree to the ethics associated with the fact that land is a gift of nature to which we should all benefit and that the rent that is taken from site users (and implied when these are also land owners) is retained instead of being shared. Indeed the concept of the taxation of land values is one that they can never agree to--its the nature of people who posess territory to want to hold on to it, even when it is not being used. They see it as an investment instead of as the means for benefit that is taken from the non-land owning remainder of our society. How then should we manage to convince these speculators that they can share in a more generally beneficant way what they wrongfully own?

Henry George tried, but his simple idea was called a tax (which nobody ever wishes to pay) and it reduced the income of some of the land owners (which as investors they found to be unfair).

The answer is not to appy a new tax, but that when a site with or without some building (real estate) becomes necessary to be sold, that the site itself is automatically bought by the government whilst the buildings are sold as before to a regular kind of investor (or capitalist) who plans to make good use of both the site and the buildings.

The site would then become leased to this investor, who would pay a regular lease-fee. Meanwhile the past land-lord, having become free of the need to collect any rent but having received the fair price for his/her site of land, (and for any buildings thereon) would be free to invest this money and gain interest on it in a more reliable (but probably less speculative) way that when it was being rented.

Thus a tax is replaced by a lease-fee, and an investment in a site is replaced by an investment in more durable capitalist goods, which can be traded and used to build a better business rather than by merely exploiting the rest of the non-land owning community.