Land value return is needed, pragmatic, and achievable

Video/transcript from the latest LVT Landscape LIVE event

On September 26th, 2025, the Progress & Poverty Institute and the Center for Land Economics joined forces for our first of many “LVT Landscape LIVE” events where we update the community on what’s been happening nationwide in the world of LVT and related policies, including input from local officials actively running on this issue. Many people weren’t able to catch it live; we are therefore happy to share this recording and transcription. Much thanks to our friends at Progress & Poverty Institute, especially Josie Faas and Stephen Hoskins, and all the officials and candidates who participated, for making this possible.

Here is the video in full:

The full video transcript (edited for readability), along with screenshots sprinkled throughout for relevance, can be found below.

Video Transcript

STEVE: Hello, welcome to the first of hopefully many LVT landscape LIVEs. My name is Stephen Hoskins, I’m the Director of Community Research and Engagement at the Progress and Poverty Institute, where I work a lot of the time on analyzing the impacts of land value taxes in different local jurisdictions.

And I work very closely with Greg, who’s my co-host and will introduce himself in a moment. And so the purpose of the event today is we want to sort of update you all on the state of LVT advocacy around the US mostly. I know we’ve got some Europeans, but hopefully you’ll be interested in what’s happening in America.

As of fall 2025, and we want to give you some sort of general tips as well about sort of how to get the ball rolling in your local area with the same type of work.

We are a little short on time, it’s only going to be an hour. So we’ll ask you to not jump in with voice with your questions and just instead put your questions in the chat as the event is going on.

We’re going to collect those and we’ll have 10 to 15 minutes to address them at the end of the event. And also at that point, they’ll also be time for people to jump in and ask questions vocally if you’d like to.

So I’m going to hand you over to Greg, and he’ll introduce himself and get us started.

GREG: Thanks, Steve. Hey, everyone. I’m Greg Miller. I’m co-founder of the Center for Land Economics with Lars Doucet, who you will hear from later on through this presentation. We have been working closely with the Progress and Poverty Institute as well as many of you in this room right now and appreciate you all coming out.

As Steve said, this is us trying to sort of show what we’re doing, and so that way you all can learn from what we’re doing and maybe teach us what we’re not doing right or what we could be doing better. And then with the ultimate goal being that there’s an end policy here, there’s an end vision here, Henry George being the aspiration, but the policies in between that can get us closer to that world.

And so I’ll kick us off and get started as people still trickle in, but the first thing I want to say is:

Land value return is needed, it’s pragmatic, and an achievable policy.

And I say those three things, and I’ll go in more depth on what I mean by each of those.

The needed part, a lot of us are going to agree on.

The pragmatic and achievable, sometimes I hear us Georgists, if you’re a Georgist in the room, complain about how it will never become policy. And then meanwhile I’m in DC, I worked at housing development and I often go to housing think tank events and folks will be like, yeah, it sounds like a good idea, but it can’t be achieved. “It’s not pragmatic.”

And I think that the mind of thinking is wrong.

And if we can change that mind of thinking, and if we can talk about land value return much more at a basic level, then we can see a lot of change. And that’s what we’re seeing right now is a lot of momentum on land value tax and land value return.

I also highlight that return part because when you talk about taxes, it’s boring. When you say land value tax, it sounds like a different tax. We’ll be coming out shortly with some message testing research we’ve been doing, but “land value return” is a much more approachable policy, a much more approachable concept.

And that’s what we’re trying to do. We’re trying to return the value of land to the community that makes it valuable.

So let’s go through each of these individually. The first is that:

Land value return is needed

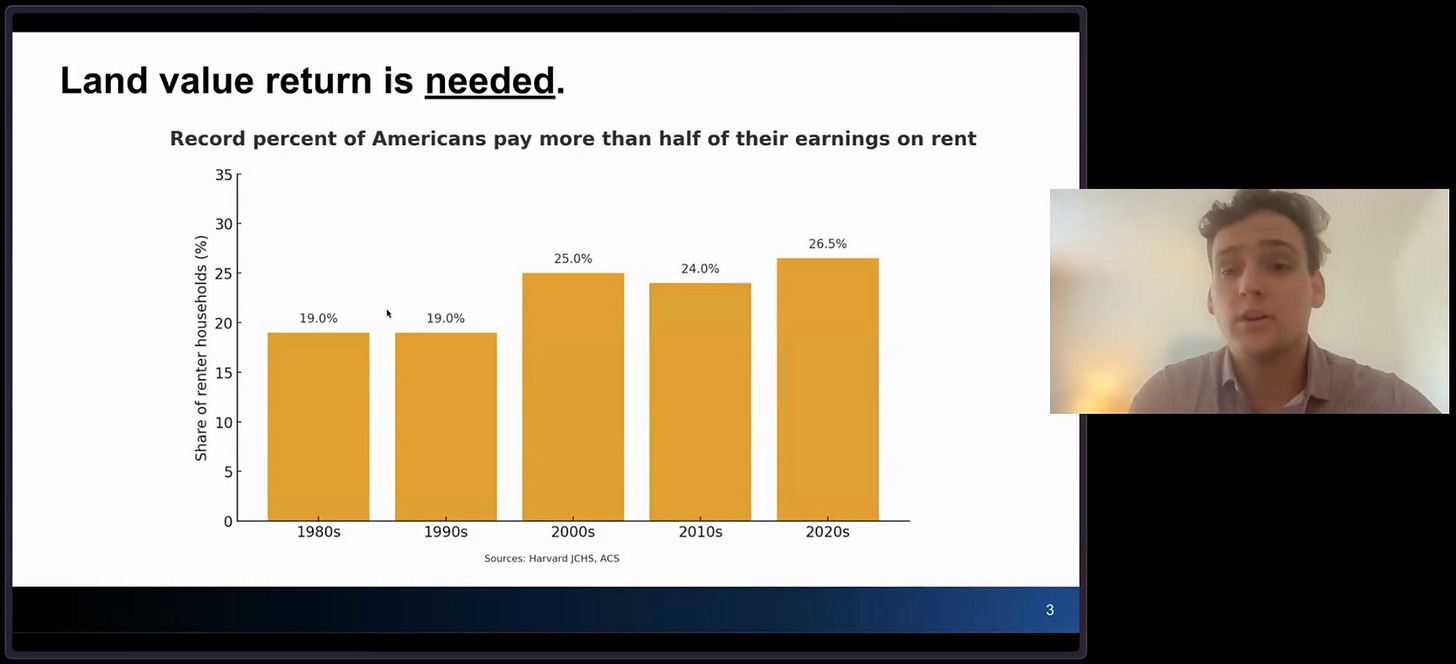

I really don’t want to spend much time here, but we’re seeing record high levels of Americans paying more than half their earnings on rent. So we’re seeing extreme rent burden.

And I think a lot of us know the issues. We have a lot of our fiscal environment in our urban cities isn’t great. And meanwhile, we’re seeing exponentially high housing costs and exponentially low home ownership, particularly among the younger generations.

So I think that this is a room that probably agrees that land value return is needed.

The question is, can we achieve it?

And that’s where I want to say:

Land value return is pragmatic

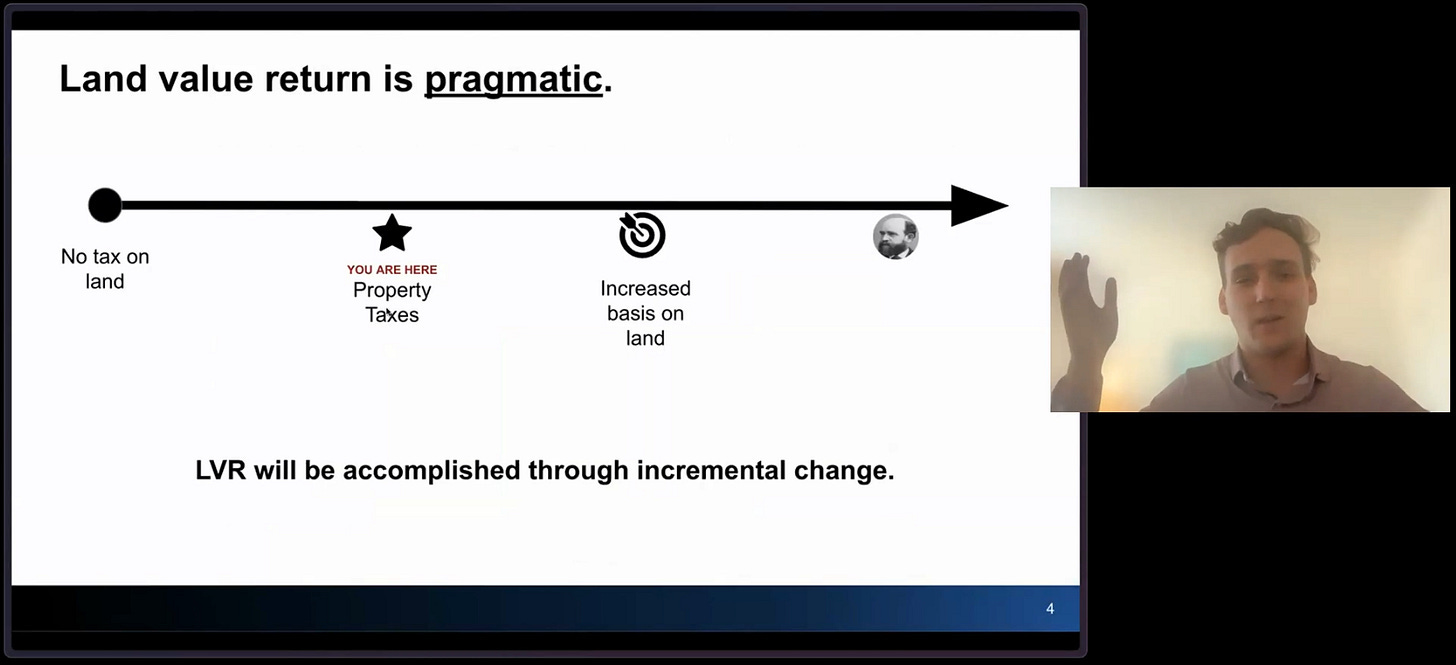

I want to first start by saying that we’re not at Henry George, but we’re not at the opposite side. We’re at somewhere in the middle where we have property taxes in our American cities and across the globe too. I should say that a lot of what I say will be sort of US in context, but I think a lot of this applies internationally in nature. And so we’re somewhere in between this spectrum.

And I would argue that land value return will be accomplished through incremental change. We don’t want to shift to a full land value tax overnight because it would destroy our economic system. Loans are collateralized on land value and our financial system has in some ways adjusted to the fact that we don’t tax land.

But we can do better.

We can start from this property tax system we have and we can increase the basis on land. And over time we can learn from how we do that and approach this end goal.

So land value return is pragmatic. How can we do it in the United States or in other structures that have property taxes? How can we get from that property tax to an increased basis on land?

There’s plenty of ways to do it and I want to focus on two ways that we’re actively seeing being used in American cities or at least considered.

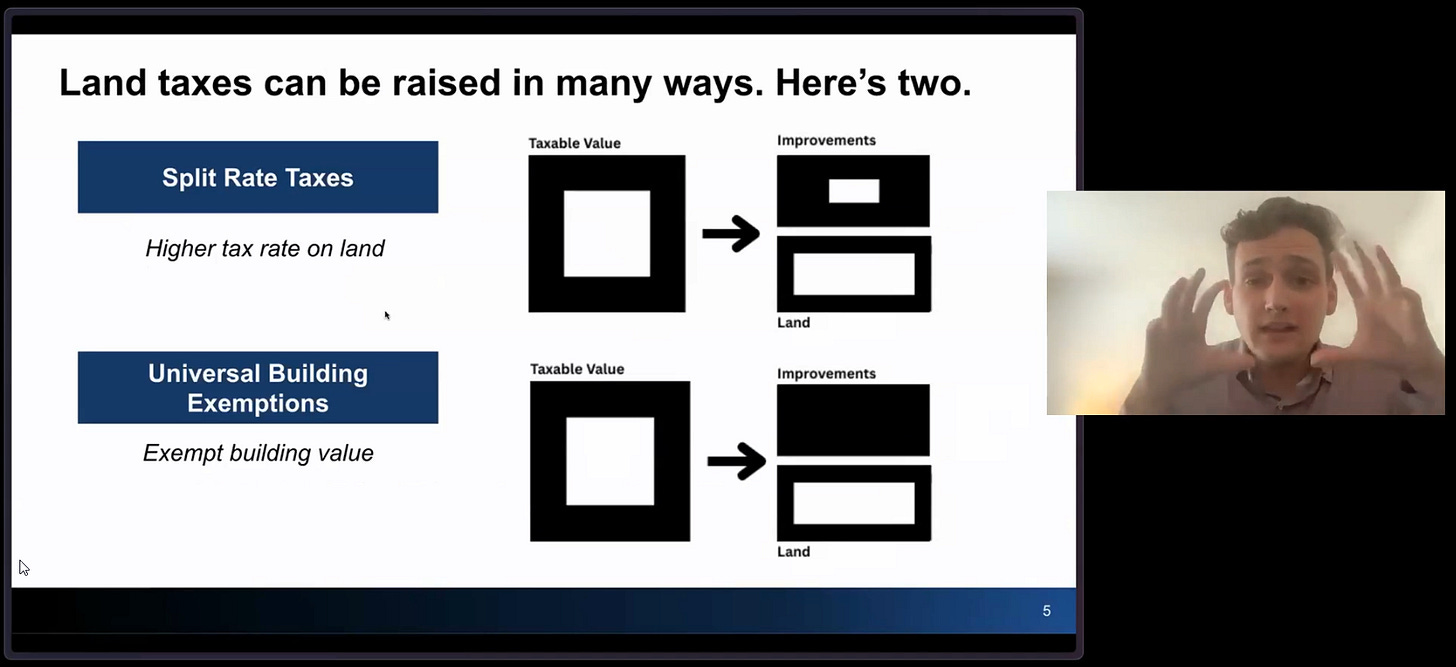

The first is through split rate taxes.

Right now our property tax structure is assessed both on the land value and improvement value. If I tax 2% of property, I’m taxing the full property value. But as we know, land is a special and uniquely different type of tax. And so you can increase the basis on land itself and decrease on improvements.

[Editor’s note: this diagram had its labels flipped in the video, we unflipped it for this screenshot]

What you’re doing there is by decreasing the rate on improvements and increasing the rate on land, you’re saying we want to tax less buildings and we want to tax more land.

We want more building and we want less speculation. And that’s the way I frequently talk about this with politicians. We’re not trying to raise taxes. We’re trying to be revenue neutral. And we’re just trying to encourage more development. At the same time, we’re trying to decrease speculators in our cities, particularly among our main streets.

The other way to do this is through universal building exemptions.

It’s functionally achieving the same thing, except just slightly different.

If you know how property taxes work, it’s not that we set a tax rate. It’s that a city says, hey, I want to raise $5 million. And then the county assessor comes along, shows how much taxable value there is, and then the elected officials set their tax rate based on how much money you need to raise and how much taxable value there is.

So if you exempt buildings and you bring the taxable value of buildings down from taxation, then necessarily you’re going to have to increase the property tax rate and increase the rate on land itself.

And so this is another way to think about achieving this policy of land value return that we’re seeing actively being considered across the US in certain states.

And that brings us to the fact that:

Land value return is achievable

We know it’s pragmatic. We know it’s needed. So can we achieve it? And again, this is where historically folks in Georgism and folks who believe in land value tax have been like, it’s never going to be accomplished.

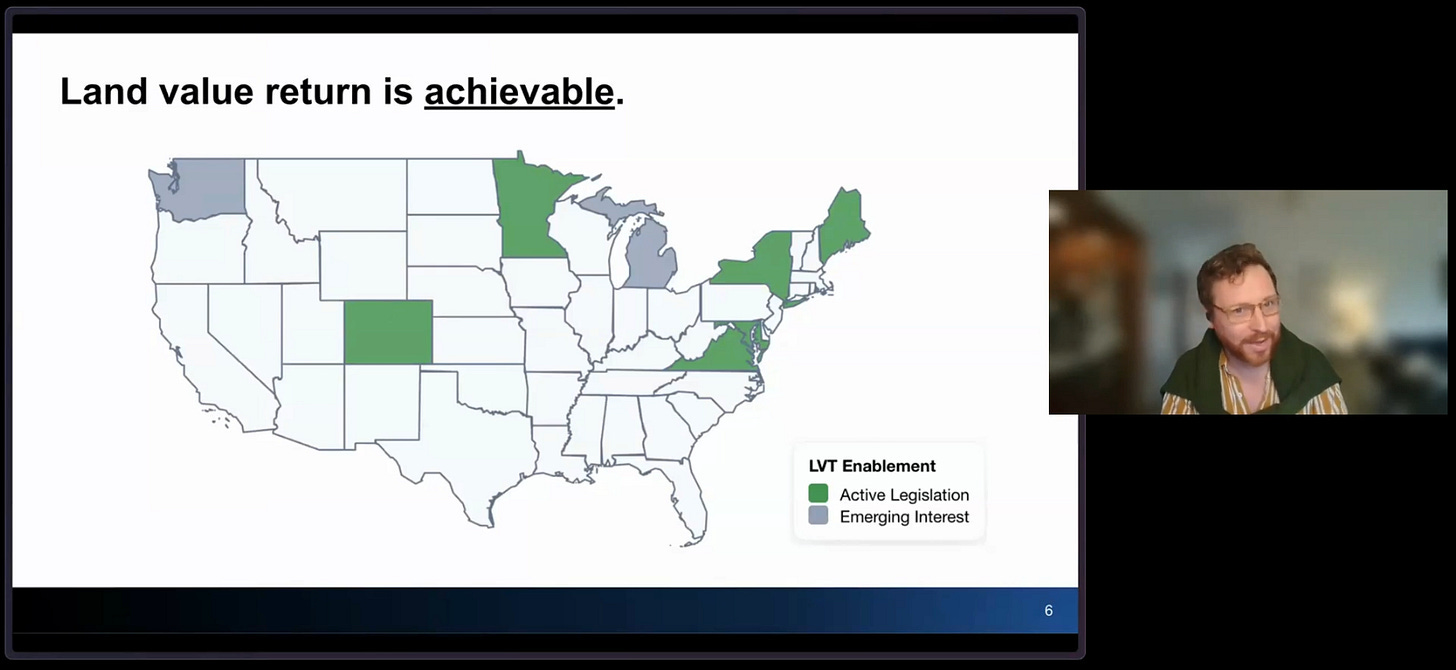

There are six states actively considering legislation for land value tax.

That’s as of the past year.

And that’s a record number and we’re seeing growing interest.

There’s also two other states with express emerging interest, as well as many other states where we’re having conversations across the nation. And so I want to talk about a couple of these.

The first is Maryland.

Maryland is already allowed cities to enact a split rate tax, and Baltimore has an interest in implementing it. Unfortunately, Baltimore is treated like a county, and so they need state approval in order to do this. But, last legislative session, there was a bill that passed the state Senate that would have allowed a split rate tax within a mile of transit corridors. So that’s already a win—it just needs to pass the state house in the upcoming session.

The way the Maryland is working is there’s an elected official who’s really interested and pushing really hard on this topic, and that’s why we’re seeing success there. There’s also the transit unions coming together with other folks in the urbanist environment to really push on this issue.

Meanwhile, in Washington state, while they can’t implement a split rate tax—we’ll go into legality later—there’s a lot of interest out of Spokane. The city council voted seven to one to look into this issue. And now they’re pushing really hard to figure out how they can pass the universal building exemption from the state enabling them to pass that. And I’ve been working heavily there, and in part, we’ll go into this later, but it was really through doing the hard work of the legal analysis, the data analysis that has pushed this interest a lot further than it has gone, and I would be surprised if you don’t see legislation introduced and make it very far in the next legislative session.

So I wanted to sort of tune in onto those two points. Also doing work in New York, a little bit of Minnesota. But I’ll pass it over to Steve to talk a little bit more about some other stories and then to move us along.

STEVE: Yeah, so to sort of focus on some of the emerging interest places, I’m sure many of you were excited to hear about the Detroit land value tax that was being championed by the mayor a couple of years ago.

So a couple of lessons from that one is that being flexible in the design of the policy, listening to the feedback from the public and adjusting what you’re advocating for to sort of make sure that it fits your local political context is really, really important. And Detroit was a fantastic example of this.

In particular, there are big issues with trust in terms of people’s relationships with the assessor. And then also side lots, which was that the city had made it really easy to acquire adjacent properties to your own to sort of turn them into little gardens and side lots as a way of dealing with blight in the city. And so sort of immediately turning around and taxing those was going to be wildly unpopular. And the design of the policy was adjusted to deal with that. So yeah, great lesson there in terms of being flexible when you’re on the ground.

And the sort of state there is that the mayor, Duggan, who championed the policy, he’s currently in a long-term campaign—I think it’s end of 2026 for governor of Michigan. And so sort of, I guess the hope is that he’ll continue to champion it once he’s at that position. And really the only reason why the legislation that was enabling the LVT died in Detroit in Michigan was kind of interpersonal politics, which sometimes there’s nothing you can do about that.

I might sort of skip a couple of the ones I was going to mention here.

Illinois, I think, is a really good example from the work I’ve been doing in the last few months of one person on the ground just bugging the hell out of every elected official they possibly ever meet. And this was being done by Gabriel Nagy, who’s one of our board members, can get you into so many warm doors and get you in front of elected officials and getting the chance to pitch the policy. And as a consequence of this, we’ve got a date scheduled to present on LVT with the statewide property tax working group.

I highly recommend that all of you, whenever you’re working with your local advocates and whenever you’re interacting with city officials or state officials, you can really get a lot of movement going that way.

And I think I’ll leave a couple of the others just in the interest of time.

Kick-start your local LVT advocacy

It’s my experience that there’s kind of like very thin but spread out interest in LVT all over the country. And what we as a movement really need is to knit some of that together and kind of congeal efforts in particular within a state so that you’re all talking to each other.

Some of the work that Greg and I do well is either being done by your teams on the ground, which, you’ll find it easier because you have the local insights, or that you’re doing the organizing and then feeding back to us on what you need in terms of research, analysis, white paper type stuff, tools that Greg and I can put out, to kind of enable the advocacy on the ground.

In particular, because I work for what is a private operating foundation, we don’t do lobbying. So we really want to just be helping you with the analysis and the research. So this is kind of sort of key steps to kickstart your local LVT advocacy.

Policy work requires doing the grunt work

These are the kind of four things that you really need to do, before you start, getting out there and having conversations and, spamming out emails and things.

And the main lesson to take here is that elected officials, they do not have the time to do this kind of in the weeds work. But if you do the work for them and you come to them equipped with it, you can really get them excited and motivated and, get a lot of momentum going from the elected officials themselves, and they’re the ones that have all the existing networks. So the four sort of chunks of things you need to do:

First is legal analysis, which I’ll step you through in a moment. You need to understand what is an LVT going to look like in my state? What am I allowed to do, legally?

Second is data modeling. So this is both looking at land valuations and understanding how high quality they are and whether work needs to happen there. And then modeling what an LVT shift is going to look like in your area. Everybody wants to know this, elected officials, they just their first question is going to be, okay, but who pays more and who pays less? Because that’s how the politics will play out for them.

Third is to tell the story, to take those numbers and turn them into a coherent story that’s compelling.

Last is to build your coalitions and start building from the ground up.

They don’t necessarily have to happen in that order. You can do the coalition building at any point, but these four things sort of have to happen before you’re going to have any kind of successful momentum.

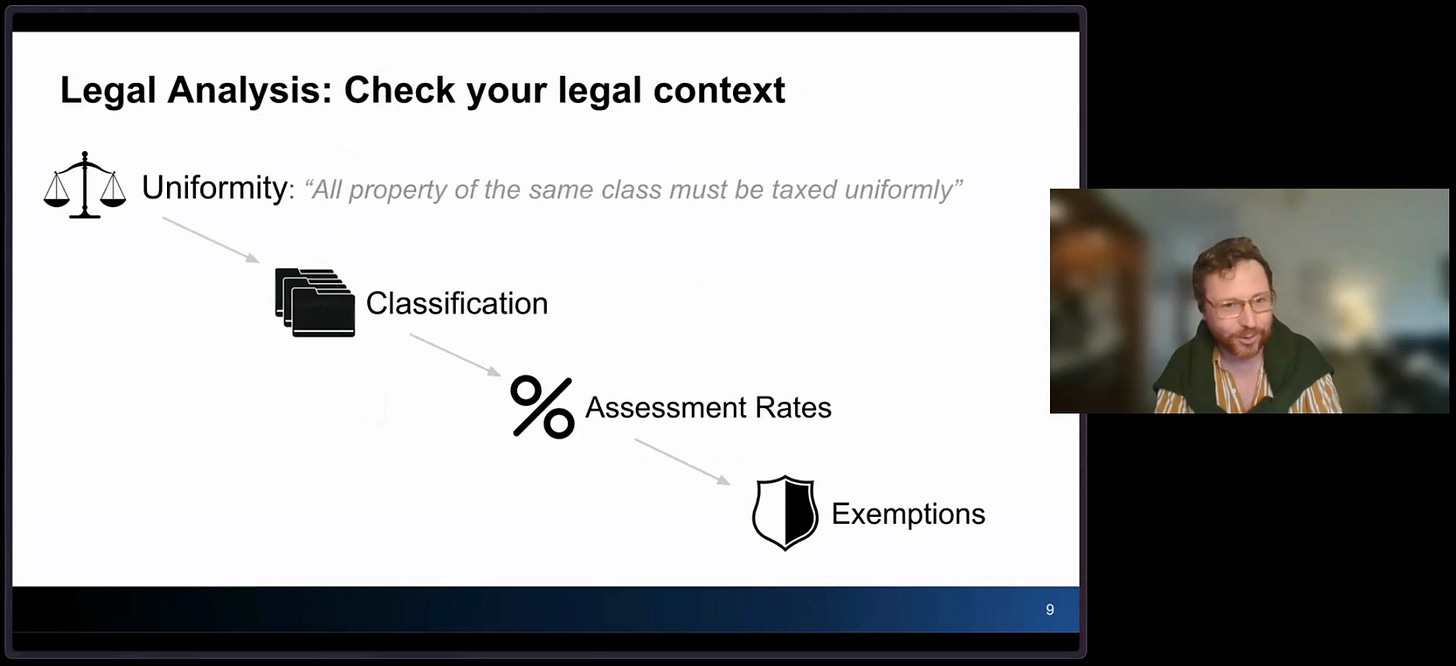

Legal Analysis

So to sort of turn to the first of those, which is the legal analysis, this is very complicated and very state specific and requires a lot of local legal knowledge. I am not a lawyer, although I play one on Zoom calls sometimes.

But here are the kind of the broad, the gauntlet of things that you need to run through at a shallow level to really get a sense of where you’re at.

So first of all is uniformity. A lot of states have a constitutional clause or some kind of legislative act, which says all property needs to be taxed at the same rate. And that’s really devastating to us, in particular, in cases where land and buildings are forced to be the same type of property, because it essentially means you need a constitutional change to do LVT. And just to be clear, I think it’s 42 states in the US have some form of uniformity clause. But critically, those are different in each state. And sometimes what they’ll say is “all property of the same class has to be taxed at the same rate.”

And that then opens the door for the second stage, which is classification. Then the question is, okay, who has the right to set those property classes? Sometimes they’re set in the Constitution, sometimes they’re set by the state legislature, and sometimes they’re devolved to specific cities. But that is going to be your answer. If you have a uniformity clause, but you can do separate classifications, then the question is, who do I talk to about creating a land classification and a building classification?

Underneath that is the first of the loopholes, which is that a lot of places, they will have market value of property, then that gets multiplied by an assessment rate, and that creates the taxable value. And so Colorado is a great example. You are allowed to have flexibility in your assessment rates, but then once you’ve applied them, you then have to tax everything uniformly. And this creates a little loophole for taxing different types of property at different rates, in which case you can do the land and building split.

And then lastly is exemptions and other kind of workarounds. So in some places, well, in a lot of places, there’ll be various types of property tax exemptions, maybe they’re for certain types of farmers or certain types of farms, retirees, disabled people, low income homeowners, these types of exemptions are all over the place. And they often have created a legal precedent for the types of exemption we would do, which is to exempt either improvement value as it exists, or to create exemptions for when somebody renovates a property, builds a new property, builds certain types of property like affordable housing, to create a kind of lasting exemption on that value. And so this is also kind of a workaround that sometimes exists, and might create a way for you to find a policy that you can advocate for in your states.

And there’s also sometimes kind of special tax districts that you’re allowed to apply for the sake of funding particular types of infrastructure, and those can be based around land, DC as an example, where that’s the approach being taken for funding the transit networks.

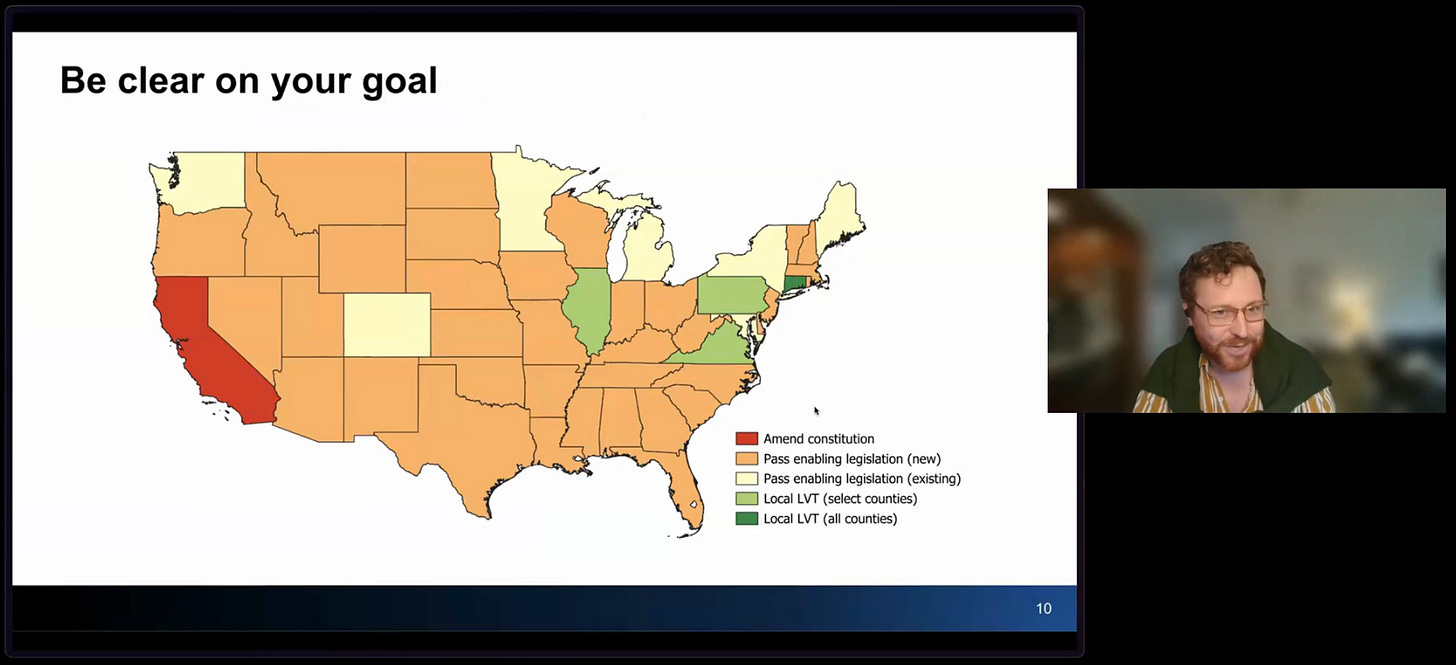

Be Clear on Your Goal

So to go to a map, so this is my medium/shallow dive into what each state needs to focus on. This is a combination of me torturing chat GPT with the various things that I just ran you through, and asking it to kind of create a grid of what this looks like for each state, and then kind of a little bit of reinforcement with me then going through specific states where I know the details, and sort of tweaking what the result is there.

So I think the lesson is I don’t think you can just use AI to get you the answer, but it can get you started, and then you can start diving in to, what some of the specifics look like at that medium level. And then the deep dive goal is to come in with this medium level, when you’re talking to advocates and officials, and then they often have access to resources like legislative aides and attorneys, who can write formal opinions. That happened in Virginia; an advocate talking about LVT led to the state attorney, Attorney General (I think it was) writing an opinion saying LVT can be done this way.

So just to kind of give you a skim through this map, what we’re looking at here is that, it’s green to read from how easy it is to do an LVT at the local level. Red means we’re pretty sure that the Constitution just says you can’t do it. And unfortunately for California, you appear to be from my analysis the only state where it’s just a blanket, “you can’t do this without amending the Constitution,” both to get rid of Prop 13 and then also to split land and buildings apart in the uniformity clause.

And sorry, Alaska and Hawaii should both be orange. Apologies for not, moving them in here. They’re in the second tier, which I’ll talk about in a second.

So the bare minimum in California, and this was what Assembly member Alex Lee was trying to pass, was a land value tax study bill. So this is not even enabling it. This was just to analyze it and talk about what it would do and sort of try and make the case for it.

So that’s the bare minimum in the orange states. This is the typical state in the US is that there’s a uniformity clause that allows splits by class, and you need the state legislature to create a land and a building class for you. So that is what those orange states are going to need to start with.

And then the yellow is a slight improvement on that, which is that, yes, it’s in that same situation, but we know of some existing legislation that’s being worked on or advocated for at this point in time. So some good examples are Washington, as Greg mentioned, has worked on a local option universal building exemption. So this is exempting improvement values as a workaround. New York is a good example where there’s a bill which would do an LVT pilot. And this exists in some states as well as enabling legislation for a certain number of cities to do an LVT pilot if they want to.

And so to go into the light green, this is places where you can do a local LVT, but it’s only in select counties. So Pennsylvania has enabling legislation in law for tier one and two cities. This is medium to big cities. This is what enabled it in Pittsburgh and many of the surrounding smaller cities, Allentown, Harrisburg, that sort of thing.

There’s a question about whether Philadelphia can do it as a tier one city, but there is an opinion out there that says that you can. Illinois, interestingly, says Cook County is allowed to do its own property classification, so Cook County on its own could do an LVT. And then Virginia has four cities have been explicitly told that they’re allowed to do LVT there.

Then deep green is the one state, Connecticut, where there has been enabling legislation that says any three municipalities can do an LVT and that’s on the table for waiting for someone to pick up and run with it. So that is close to our best case scenario. And as far as I can tell, it’s only Connecticut that’s at that stage at the moment.

When you form up your local advocate groups and then get in touch with us, we can start looking at the real nitty gritty of your specific state and try and nudge for some formal analysis to be done by a local lawyer.

So I’m just going to pass off to Lars briefly to talk to the next stage, which is assessments.

Make sure your land values work

LARS: Right. So for the past several years, ever since I wrote my book, I looked into the history of LVT reforms and where they tended to fail was usually when people got sloppy about the assessments.

And the long story short, I think understanding assessments is really important so that we can combat illusory, barriers. A lot of people have misconceptions about what our real barriers are. If you get real familiar with assessments and assessment quality and how to judge it, you can do the data modeling so you can model the land value tax shifts and know what the political math works.

But you also need to know whether your existing land values are good enough or not. Now there is a narrative both on the LVT critic and on the LVT supporter side that assessors are just universally bad at their jobs. And so we have this, “we need to go and fix all these land assessments.” What’s actually the case is that you only hear about assessments when they’re bad. And I’ve just come back from the IAAO meeting, that’s the standards body. And I know a lot of assessors, a lot of them are very hardworking. Whether the assessor really cares about land value theory or not, they understand a lot of these things we talk about all the time a lot better than the average person, because it’s their job every day.

The “sales adjusted cost approach,” the most common assessment method, isn’t perfect, but in many cases essentially forces the assessor to value land because that’s the only way they can add to building replacement costs to fit the market value sales they see. And a lot of them are already required to value improvements and land separately.

Basically, what I’m trying to say is that don’t assume that the land values in your jurisdiction are bad, they might be perfectly acceptable. And if they’re good enough already, then you have one less barrier because then you don’t need to convince someone to replace them. The other thing I would recommend is try to avoid dumping on the local assessor because the local assessor has a thankless job. Everyone already hates him or her (also, local assessment is literally a cross section of America, so it’s actually quite a diverse career). Try to thank them for their service, get to know them, and they’ll see you as a friend who’s trying to make their job easier rather than making their job harder, because they do actually have a pocket veto on your whole policy.

In the heyday of the golden age of Georgism, there were plenty of places with the Fells Fund and all that that got their enabling legislation, got their legislative LVT, and they just made enemies with the local assessor who was just like, “I’m just not working with you.”

The other thing is that if you just make sure that the local land values are accurately valued, you will move the local property tax in a net Georgist, net LVT direction, just because land is no longer being undervalued. And what I advocate for, the lowest hanging fruit reform for assessments, is if you revalue every year, and you collect good data, it almost doesn’t matter what method you use to value land and improvements. You will get better if your local assessor is just putting in the reps and collecting good data. Data quality, trumps algorithms over everything, that’s kind of the limit of my spiel.

Steven and Greg, if you have a quick question, you want me to address or something, I forgot to say, I’ll do that, otherwise I’ll return the time to you guys. I know I talk too fast, everyone always says that.

GREG: Great, thanks Lars. Yeah, and to Lars’s point, assessors do have pocket vetoes sometimes. And this is what we’re coming into in Maryland, where Lars and I put out a report on Baltimore on their chronic under assessment of vacant land. We don’t expect this to be nationwide. So people have reached out to us like, is this everywhere? We don’t think that issue is everywhere. We’ve seen it not be everywhere.

But also because Lars and I have sort of owned this issue, it’s given us sort of the narrative, the control of the narrative. And so that’s where we say that whether it’s assessments or whether it’s just the policy, if you own the narrative, if you do the hard work, then you can control the narrative in some ways.

Data Models

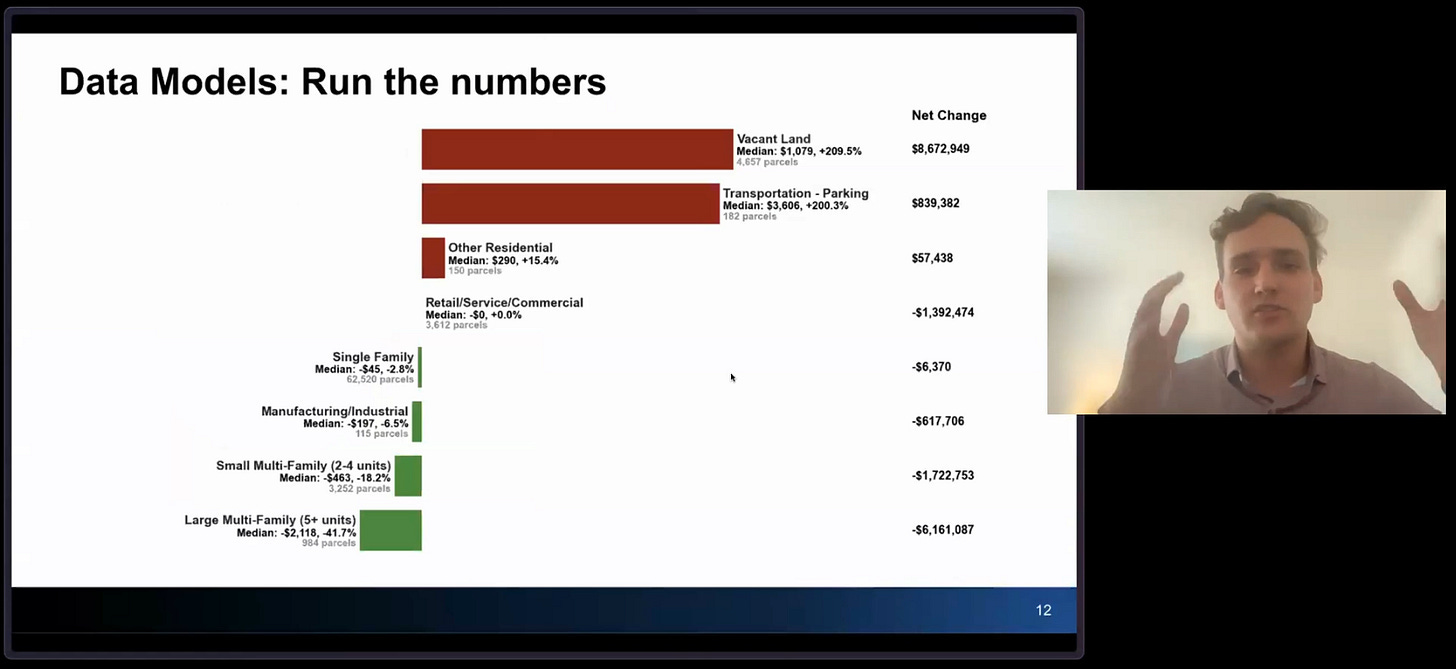

And so the next step to this is the data really matters. Data models, run the numbers.

And as I said, I’ve been doing work in Spokane, as Steve pointed out, when I first started this, I was like, it’s impossible. They very explicitly define in their constitution that you can’t tax real property at split rates.

And then I said, well, what if we did a universal building exemption? Just about every state allows for exemptions of property in some capacity. And it turns out that’s completely allowable, and the state might bite on this issue. And it was because I did this analysis that really pushed this policy forward. I sent this analysis of data around to folks.

And so what does universal building exemption do? Spokane would collect the same amount of revenue, but it would double or triple the tax that vacant land pays. It would double or triple the tax that parking lots pay. And meanwhile, single family is really not impacted at all. And small multifamily sees a large decrease and large multifamily sees a large decrease. That’s by design. We’re shifting taxes from productive use cases to unproductive use cases. And that’s exactly sort of the land value tax at work. That’s the universal building exemption at work. And so this is one way to do the analysis.

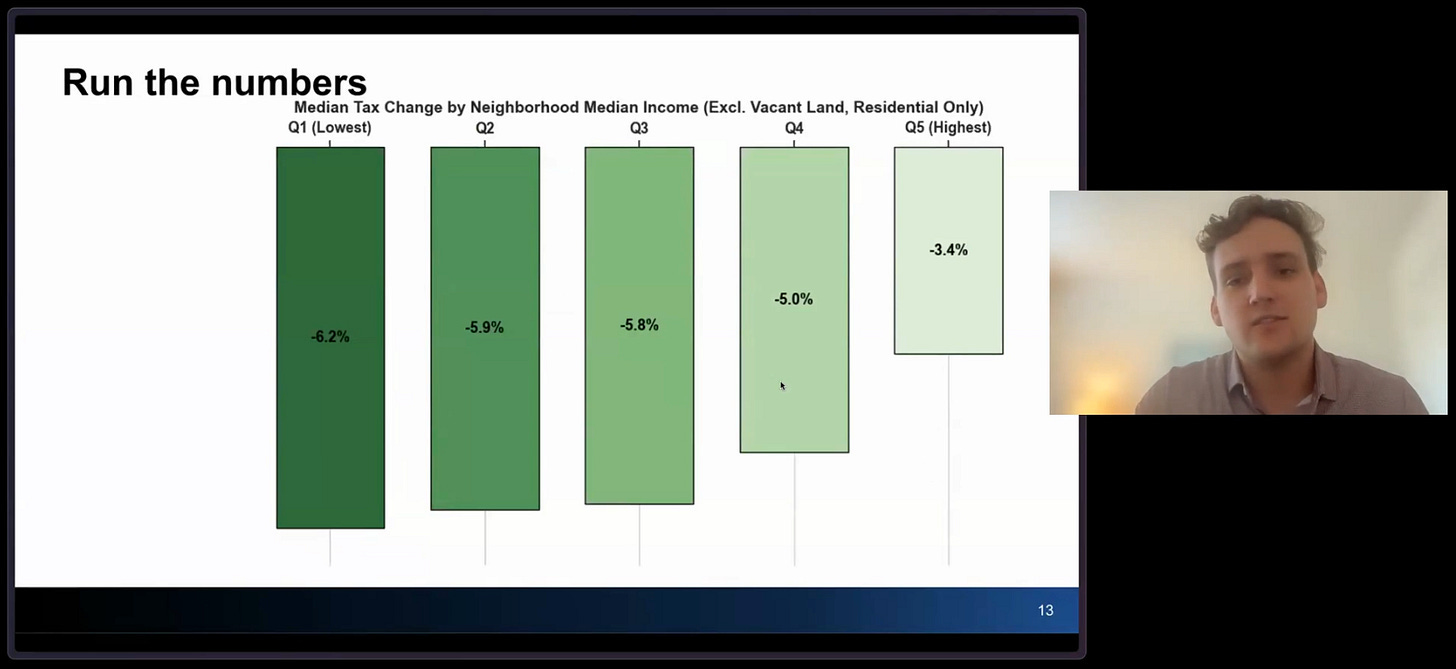

Regressivity?

This analysis also matters in terms of one of the first questions you’ll get is, will this be regressive on property tax structures? And so I also run that analysis.

Luckily in Spokane, it appears to be pretty progressive. We see that the quintile of the lowest median income sees the largest tax decrease compared to the highest median income quantile of neighborhoods. And this is excluding vacant land. So if you’re wondering how they all decrease is because vacant land is the part that sees the increase, we don’t really care about the vacant land owners. We care about the property owner in each of our neighborhoods. And so is the single family low income household going to be impacted more? And the answer is no.

But this kind of analysis doesn’t get at the point of what we want to do with land value return. The land value return is not about an immediate tax shift impact. It really matters that you run this analysis because city council members and state electives will ask about it who immediately gets impacted. But as we know, we care about the long term trajectories are of our cities.

We want to create the incentives for those long term trajectories. 50% of people in our cities don’t even own property to begin with. So obviously, it’s progressive when we tax land more because 50% of our city’s people don’t own land.

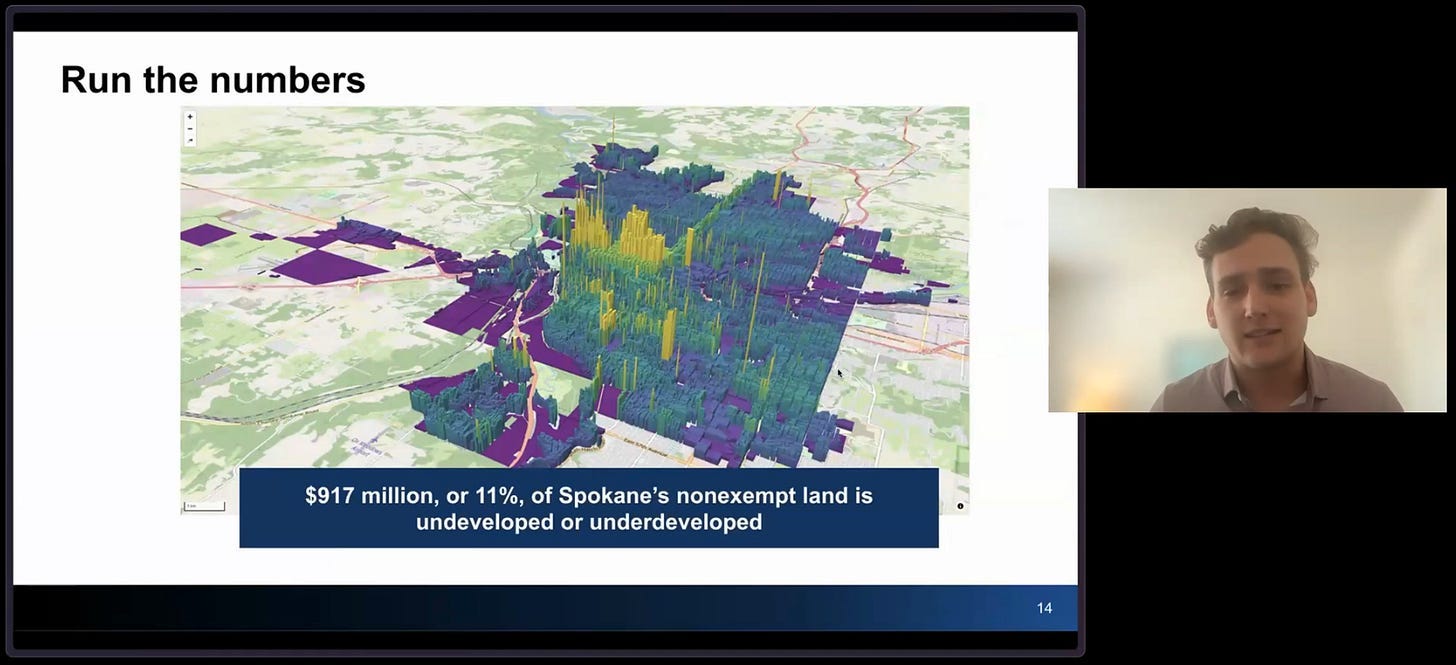

Put it on a map

So to get at some of this, there’s also mapping, throw things on a map, and we’re working on tools to do this.

And the other thing that you can do is you can just add up the total number of under developed or vacant land in the city.

So Spokane has 900 million, almost a billion dollars worth of land that they can build upon that they can have more improvements upon. And so these are the types of things that we’re trying to do when we’re running the numbers. We’re trying to tell the long term story while also answering the questions of the short term immediate tax shift impact.

And when you do this and we show these stories and we do it with the legal analysis, that’s what really frees up the city elected who’s a champion of the cause but doesn’t have time to really care about it be like, this isn’t just a cause that I’m a champion of this is a cause I’m going to send to our state official because this analysis you’ve done has basically prepared the case for me and put it on a platter. And I think that’s what we want to try to replicate.

And all of the tools I showed you are open source. Lars and I have been developing a ton of tools open source, including this mapping software, including all the LVT impacts. And so we’d be happy to sort of work with you all on those issues.

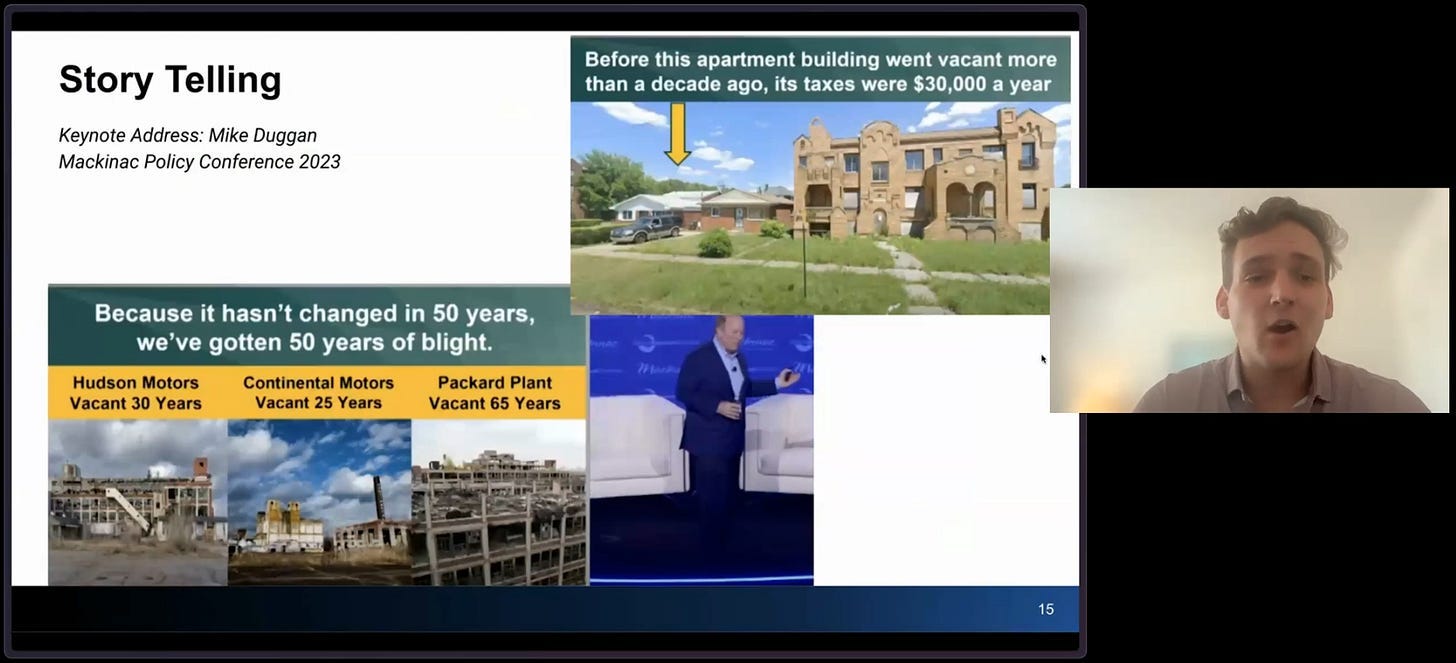

Story-telling

The next thing is storytelling. If you have not watched the Detroit mayor, Mike Duggan speech in 2023 at the Mackinac policy conference, I really, really, really recommend it.

He tells stories that are very convincing. Data is boring. People don’t like data. People like stories.

And when you can go into Detroit, and if you look at this top right, there’s a home that homeowners been there for 30 years and Duggan goes up on stage and tells this story, the homeowner has been there for 30 years. They’re paying double triple the tax rate as that large building to the right. At one point that large building to the right was an occupied complex that was paying up $30,000 a year in property taxes. Now it pays next to nothing. It’s deadweight loss in the city. It makes the city look ugly. It makes that person’s home. It attracts vandalism, et cetera. So that person’s being impacted by it. And yet that home owner pays more.

So that’s the type of storytelling we can do. And then you can also look towards the vacancy, the blight of your cities. I like to say when I talk to city electeds on, I say on main street, you know that one landowner who’s just holding onto land. And right away I’ll hear city elected say, I know exactly who you’re talking about. Find that person who’s holding onto land, find that plot that immediately clicks in the mind of your local city and tell that story.

Because when you tell that story, the purpose of the policy becomes a lot stronger.

Now click it over to Steve.

Coalition Building

STEVE: Thank you. I’ll just mention that I also do the LVT modeling that Greg was talking about. And actually the bulk of my work in the last few months has been people who are running for office in the upcoming November elections as local officials and want to know what LVT will look like in their area. So yeah, we can also contribute to that.

So not necessarily the last stage, but one of the important stages that you’ve got to do along the way is to build your networks of allies. And I think one point to make is that you want to do this both from the bottom up, which is connecting with local advocates and getting your sort of co-supporters along for the ride and pulling your efforts. And then also from the top down, which is to sort of talk to elected officials and get their interest going.

So this is the first bit is kind of going to focus on the bottom up bit, which is which types of people are and organizations are good ones to build networks with. And legislators, they really pay attention to and listen to nonprofits. They often rely on the expertise of nonprofits, and they often have their kind of network of ones that they trust or engage with. So this is also a really good way to get your foot in the door through these groups. So to run through a few of the ones that are on this slide here, pro housing groups are bread and butter. Our overlaps are nearly universal.

So YIMBYs, I was at the YIMBYTown Conference last weekend, anytime land value tax was mentioned, there were cheers around the room. And certainly I’ve been pretty active in YIMBY advocacy for the last decade. YIMBY are a really, really good group to connect with and then affiliated groups in the urban space like Welcoming Neighbors Network, Habitat for Humanity, and Strong Towns. They’re all just really aligned on our interests. We all want better ways to fund transit. We all want to price parking and congestion. We all want infill housing. We all want the densification. So our goals are nicely aligned and land value tax is a great way to bring about most of those goals, all of those goals. So those are good one to start with.

Environmental groups, likewise, tend to recognize these days that densification is a fantastic way to reduce, carbon use, water use, vehicle use. And so they tend to be aligned and the Sierra Club have been pretty good at allies in a couple of parts of the country. Sometimes it takes a bit of explaining to get them on board can depend a little bit on the local context. Sierra Club is often a really close ally. And then unions are really great as well, in particular transit unions. They’ve been great allies in DC, in Seattle. They see that that a lot of their work in their industry just goes into the higher land values near transit stations and stops. And they’re also desperate for more funding. And land value tax helps to both capture the land value they create and fund their services.

Some that I haven’t included here that I would sort of label as “proceed with caution,” and this is actually caution that we need to personally take in our approach, not in terms of caution in terms of distrusting them; these are pro tenant and housing justice groups. I’m talking about tenant advocacy, tenant unions, those kinds of things, and they tend to be a little bit more on the left.

These are groups that I think that land value tax has a ton of value to offer. In fact renters are the primary beneficiaries of a land value tax shift. But it can sometimes be difficult for us to convince them that land value tax doesn’t raise the rent. I think their stakeholders are often have been so pummeled by the housing market that they have an instinctive distrust of their landlords. And they tend to feel that, oh, if my landlord gets a tax increase because of this, it’s just going to raise my rent. And so there can be some very sensitive work to get them on board with that.

And the sort of second part of this is that I think that demographically and where we kind of sit in the political spectrum, Georgists tend to come in with a bit of a white liberal technocratic hat on. And that can be really off-putting, I think, for some of those groups because of bad experiences they’ve had in the past or just a general kind of lack of trust that we’re going to be there for them when the rubber hits the road. So, yeah, very important stakeholders, certainly ones that we need to get better at reaching out to. In a similar space, community land trusts sort of fit into the above description as well.

Another group is the efficient taxation groups, sort of on the libertarian side of things. Again, they tend to recognize that land value taxes are the least bad taxes, as Milton Friedman said. But just a little bit of caution is needed in so far as those kind of efficient taxation groups can sometimes just be anti-tax groups and, aren’t always actually that interested in better taxation, they just want to keep taxes low and cut them. So do your research before getting involved.

And then realtors and developer type groups, apartment associations, even kind of commerce commissions or, representatives of the business community. Oftentimes, these are really great allies. They have been in Richmond, they were in California right here that they are. But just sometimes those groups can be captured by land speculator interests underneath the surface. And so they may talk about wanting to, make the tax system more rewarding of business activity and investment and construction. But some, when the rubber eats the road, they’re a little bit like, oh, no, we don’t want to tax our land that we’re holding on to. So that just depends on your city. It really depends on a city by city basis.

And then obstacles, sorry, Greg, I’ll just do a little bit more.

Obstacles is just to say that, like, when you actually get into, talking about this in public and facing opposition, the typical types of obstacles you get are NIMBYs, simply just that we want this because it’s going to stimulate more housing construction. NIMBYs don’t like that. So you’ll run into that sometimes.

Likewise, homeowners, essentially, it can range anywhere between kind of two thirds benefit or two thirds are harmed by a land value tax shift. This is among single family homeowners. But even in situations where it’s about two thirds of single family homeowners benefit from an LVT shift, the third who lose will be a very squeaky wheel. And so that’s, that’s something that was kind of going to need to be navigated around. I mentioned that, taxpayer unions like Howard Jarvis in California, those are a big problem as well. So, yeah, one’s to look out for.

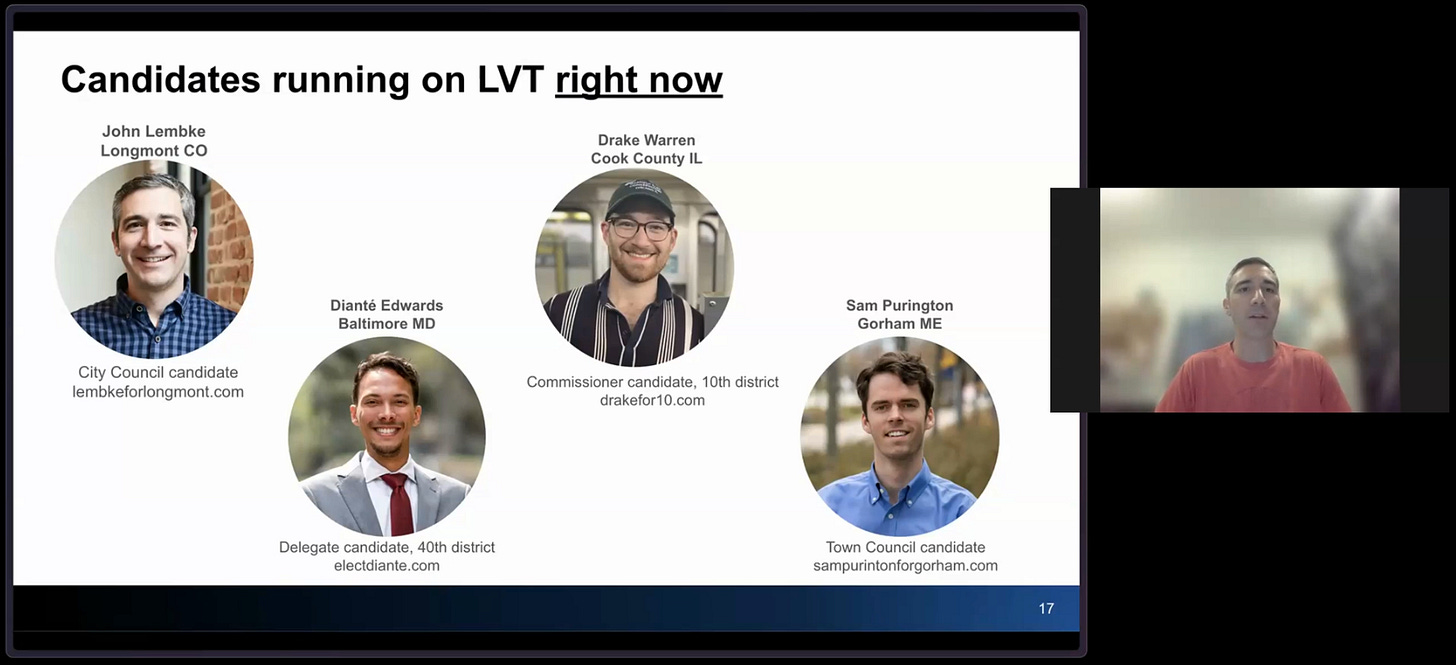

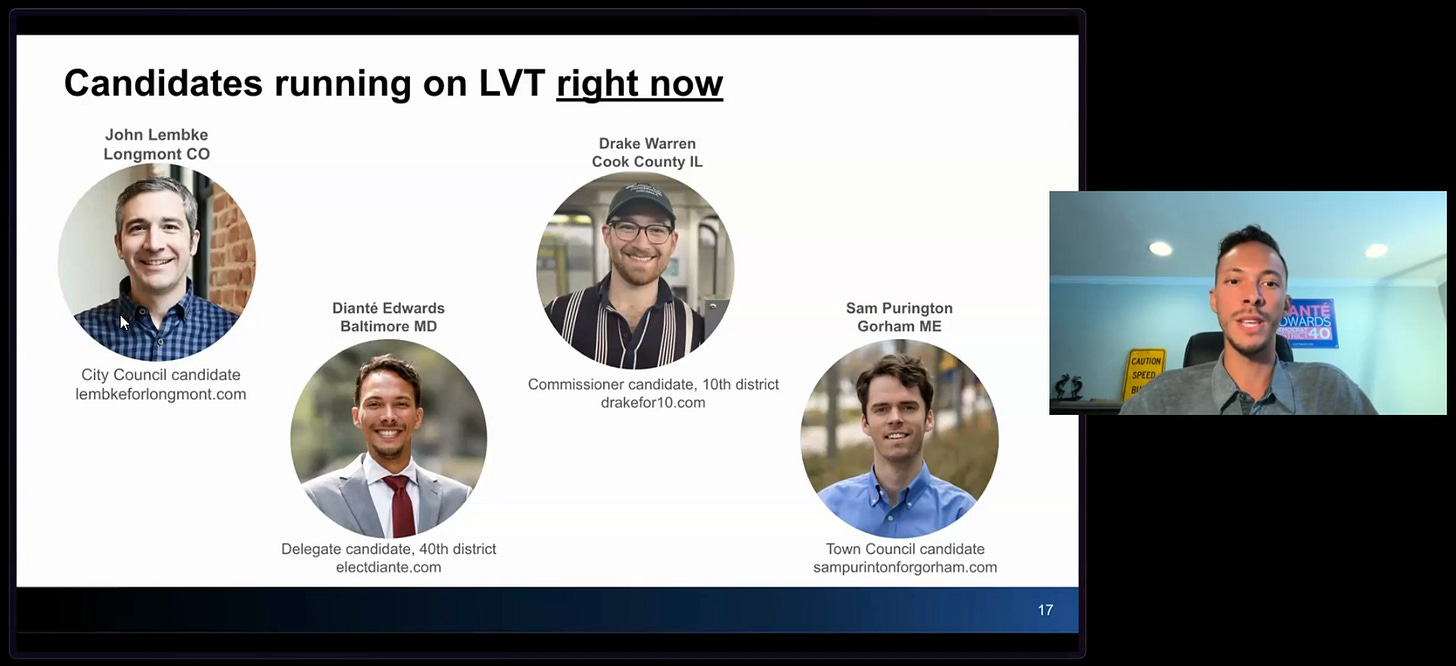

Candidates running on LVT right now

And so that was the top down, well, those kind of advocacy groups to go from the sort of top down approach is elected officials. We’re very lucky at the moment that there is a lot of interest in LVT around the country. I think in particular in reaction to the new administration, people are looking for better sources of local revenue. And there is a lot of burgeoning interest from, from local elected officials in LVT. And so we’re going to invite on to give their kind of elevator pitch these four candidates who are running on LVT right now.

I just want to be clear that from my perspective and from my organization, progress and poverty institutes, we do not do candidate endorsements. We do not do lobbying. And so we are not officially endorsing these candidates. But rather, we just think it’s important for your educational purposes to be aware of these people that are sprinkled around the country.

So, John, I think I saw you in the chat and invited you to jump in and let us know who you are.

John Lembke, Longmont CO

JOHN LEMBKE: Thanks. Hi, I’m here. My name is John Lemke. I live in Longmont, Colorado. Steve and I actually met in person in Denver. It was great to meet him. I’m running on a few different things that are big and bold, I would say. Land Value Tax is one of them.

I’m a member of Strong Towns and we have a local affiliate called Launch Longmont Housing that invited the leader of Strong Towns to come here. But Longmont, 14,000 households, so a third of the city are rent burdened, so paid more than 30% of their rent or their income and rent.

I think Land Value Tax is one of the ways that we get to help some of those folks along with legalizing more different types of housing. I mean, the other things that I’m really big on in street safety are streets in Longmont are really big and really wide for how small our city is.

We’re only about 100,000 people. I actually, some encouraging things, I went to a candidate forum, gave my pitch about Land Value Tax and then our county commissioner saw me out in public, remembered that I had talked about this, and then grabbed me off the sidewalk and asked me to talk to her friends. So, I’m happy to report that people are remembering that I’ve talked about these things and other levels of government, so I’m hoping to use her as an in to talk to more people in our state legislature. I hope to answer any questions, but thanks for having me here to speak briefly.

STEVE: Thank you, John. Appreciate that. Dianté Edwards, you’re welcome to unmute. Tell us who you are.

Dianté Edwards, Baltimore MD

DIANTÉ EDWARDS: Good afternoon, everyone. I’m Dianté Edwards. I am running for state delegate for district 40 here in Baltimore, Maryland. Actually, my top priority here is housing reform, and it’s really good to be talking about this now, especially because our mayor and our governor have taken this up as a top issue for themselves as well. I will say that my plan aligns with theirs and also very much complements theirs.

However, the main difference is that I would like to direct state funding into a land trust in order to speed the development of rehabbing vacant homes and building new homes, not just single-family homes, but we need all types of housing, including apartments, duplexes, triplexes, and really filling in that missing middle housing gap.

The current plans on the table are much more geared towards subsidizing the private sector through tax breaks, through other methods, and that is important still, but as we’ve seen for decades, the private sector only knows how nowadays to build luxury housing that no one can actually live in. That’s why that land trust model is really important to complement the ongoing work. That ties in with land value tax because at the same time that Baltimore City as a government owns over 10,000 vacant homes, there are thousands and thousands of vacant homes that are in private hands.

That shift to land value tax will really allow people to better afford to not just maintain the homes that they already live in, but fix up the houses that they own and need to develop into livable places really so that they can get their UNO and either rent them or sell them. UNO is Use and Occupancy Permit. I don’t know if that’s a thing in other jurisdictions, but it is for us here. That’s really important to really encourage that kind of development here. It does try into, I actually just got off another meeting where I talked about how that ties into our educational system and defending our education from cuts and kids that are experiencing housing instability whose parents can’t get them to school or they’re not able to get to school on their own because they’re experiencing homelessness. It all really ties in together.

Fixing that housing and rebuilding communities and rebuilding the Black middle class, especially in Baltimore, is really my ultimate goal here. If anyone has any questions, I know I slid through a couple different things there, but I was trying to be quick.

STEVE: Thanks, Dianté, and next we’ll have Drake Warren in Cook County.

Drake Warren, Cook County IL

DRAKE: Hey, everyone. Thanks, Steve, for inviting me. I’m Drake Warren. I’m a Chicago-based industrial engineer. I’m a member of YMB Action. I’m involved in my local Strong Towns chapter. I’m a huge urbanist. I take trains at all the time. I don’t own a car. And I’m running for Cook County Commissioner, which is the county that includes Chicago as well as 2.5 million other people in surrounding municipalities. And as Steve mentioned, is the one county in Illinois that is legally equipped to implement land value tax policies. And the Cook County Board of Commissioners is the exact body of government that would be implementing those policies between the exemptions, between the assessment policy, and between the property level classifications and the assessment levels.

I’m really excited about the impact that could have on Cook County because we’re very much troubled by land speculation and land underutilization in literally the city that invented the skyscraper. It’s scary how far we’ve really strayed from our roots as a city that builds.

And on top of that, Cook County is by far the biggest landowner in Cook County, public or private. Cook County owns vast amounts of vacant residential land that I want to make sure we proactively permit and upzone and offer pre-approved plans for so we can get that land developed and back on the tax rolls, so that we get lower burdens for everybody else. So I’d love to talk more with anybody who has an interest, especially if we have folks on the call who are in the Chicago area. I’m going to pop my website in the chat so you’ll have a way to get in touch. And thank you for your time.

LARS: Drake, I just want to jump in real quick and say that I was at the IAAO conference and that’s the Assessors Conference, and Cook County is famous for having some of the most sophisticated and skilled assessors in the country. And their open source automated valuation model is the direct inspiration for my own. So you’ve got some great people working with Cook County Assessors Office.

Sam Purinton, Gorham ME

STEVE: Seconding that. And so lastly, we’ll have Sam Purinton.

SAM: Hi everybody, I’m Sam Purinton. I’m on the bottom right there running for Town Council in Gorham, Maine. I started on the land value tax conversion, you might say, when I watched Mr. Beats’ video on Henry George, if any of you know what I’m talking about.

(EDITOR: Here’s the video in question)

And that was a few years ago. And in Gorham, I’ve been knocking a lot of doors. And by far, the biggest issue that residents have is the property taxes. They’ve gone way up in the last five to six years. And everybody points to the school budget. I don’t know if this is what it’s like in other towns, but everybody thinks it’s a school budget. That’s a problem. And I’ve looked at that and I said, well, there’s really not a whole lot to cut before you’re violating state mandates, which I’m not interested in doing.

But on the other hand, Gorham has a lot of infrastructure and it’s not being used. So Greg, I sent you a map. So this is a picture of the center village in Gorham. And the yellow, you might guess, is parking lot. And this is the main street. This is the most valuable land in the whole town.

And so much of that land is parking lot. And so when people talk about the property tax being too high, it’s like, yeah, we have all this infrastructure and it’s being used to service parking lots that pay like a fifth as much as that Hannaford building does or that Goodwill building does. Or you see, if you can notice that small red rectangle on the left there, yeah, where the mouse is, you could go to the next slide.

That rectangle is that very cute apartment over a retail space. And that apartment over the retail space pays at least five times as much as any of those parking lots do.

And if you could go back to the map, ArcGIS tells me that the area of yellow is about 250 times the area in red. So I think this is a really strong indicator that Gorham has way too much infrastructure for what it’s supporting. And we need to change that we need to make much better use of the infrastructure, if you want to keep the property tax burden down.

But right now, because of the way property taxes work, people are actively disincentivized to improve their property and to make better use of the infrastructure. So I think that the land by tax in Gorham or split rate or universal building exemption or whatever form it takes in Gorham is a important step towards making better use of infrastructure and keeping the property tax burden low.

STEVE: Thank you, Sam. And thanks to all four of you. A couple that I didn’t mention are here in Seattle, where I live. Katie Wilson is running for mayor and she’s a land value tax supporter. And I think I think likely to win, maybe. And then Keith Linares is in Worcester, Massachusetts. I think he’s running for district one there. He’s also a land value tax supporter in public. So yeah, if you’re in either of those states, you might be interested in those.

Well, Greg, I’ll let you kind of reiterate this message if you like, and then we’ll do the final slide.

Land value return is needed, pragmatic, and achievable.

GREG: Land value return, as we said, is a needed, pragmatic, and achievable policy.

And I think that’s also one thing that that has been sort of through this presentation, I want to say explicitly is oftentimes is better to convince the person who makes the policy than it is to convince the entire populace, right? It’s easier to convince one person who cares about urbanism, who happens to be on a city elected official through doing all of the hard work. And you can achieve much more that way than you can through building a whole bunch of people who who then try to call the city council members and try to force them onto the train, finding that one champion inside and really helping and working with them is a lot more powerful in a way to get the land value return as a policy.

So thank you all for sticking with us. And I’ll let Steve talk about next steps.

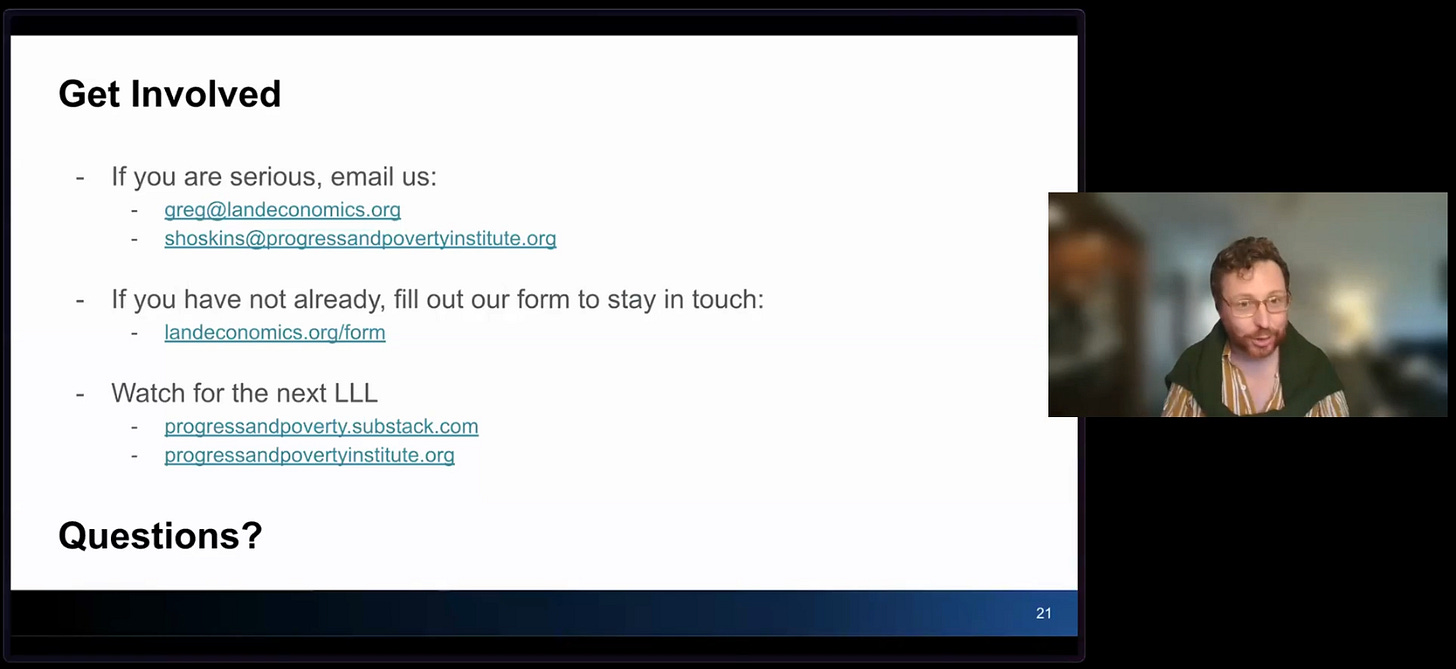

Get Involved

STEVE: What we’re looking to do is to coagulate the disparate interest that exists within each state. The first thing to do is that if you’re really serious about wanting to see movement in your city and then using that to kind of get progress in your state, and you’re willing to actually put some effort into that, and that is things like making phone calls and sending emails and talking to people about it locally, joining groups, and/or helping out with some of the the modeling, running the modeling in your own city with a bit of our help or analyzing the legal stuff.

If you’re willing to do a bit of effort and you want to get involved, email Greg and myself. We’ll treat you as the as the local person on the ground that we can provide resources to in our work.

Secondary, if any of you in the call haven’t completed the form that Greg and I use for sort of being aware of where the land value tax supporters are, that’s the middle link there. Just let us know who you are, where you are, and, and, what your sort of skills and interests are, and that’s just helpful for us, when there’s things happening in an area. And then we intend to hold another one of these LVT landscape live events in another month or two.

The goal there is that that’ll be starting to hear from some of those, local efforts that are spinning up and a little bit less of us talking at you. So to watch out for that, you should be keeping a track of the progress and poverty substack, which is where Greg and Lars are writing most weeks and I occasionally chip in.

And then on my organization’s website, progressandpovertyinstitute.org, likewise, we’ll, keep you abreast of those. Thank you for the time that you’ve given us.

Questions

STEVE: With the remaining time we’re happy to talk through a bit of the questions that have come up from chat for the next, I guess it’s three, but we’ll probably run a little long and address some of them after that.

GREG: And while you’re talking, Steve, I was going through and seeing some, and so I’ll take some that I think I can answer pretty quickly.

Q1: What does Universal Building Exemption apply to?

Ross asked about the universal building exemption in terms of “whether it applies to improvements on other types of categories like irrigation, utility systems, et cetera.”

It’s an interesting point, right? So when we assess farmland, we assess the land value, but there’s a lot of improvement done on the land itself.

And for those reasons in the places I’m proposing universal building exemption, I am also proposing that we build exemptions around farmland—farmland is often already exempt—such that farmland doesn’t inherit a lot of the tax increase. So we hold farmland even and everything else sort of moves around or shifts around farmland, because otherwise farmland would increase a ton even though a ton of improvements are done to the land itself.

LARS: Also consider that in assessment world, things like timber and trees are considered an improvement, irrigation is considered an improvement, permanent machinery on site is considered an improvement. Exact statutes vary from state to state, but in a general appraisal theory, those things are generally considered improvements.

Q2: How do you identify parking lots?

GREG: And then on the parking portion of this analysis, actually assessor’s data is often very good. You can assessor’s already categorized data, and so I just use the assessor’s categorization of data. Now there’s additional analysis we can do on top of that because some categories are defined as commercial, but obviously it’s like a burger king on a large law. And so future analysis, I can sort of parse out that impact, but for now it’s just full parking lot structures. I use the assessor’s data in order to do that analysis.

LARS: Most commercial data vendors just copy the assessor’s homework and resell it anyway.

Q3: What about using “Location value tax” instead of “Land value tax?”

GREG: Now, there’s another question about location value tax. I often say the value of land is determined because of the location, right? But I want to stress that you should always use the term shift and in fact, I try to emphasize first the decrease in building tax. So I say we’re going to shift taxes off of buildings. We’re going to decrease the building tax.

We’re going to offset that by increasing the burden on land itself, which is tied to speculation. And then yeah, I’ll talk about location. I haven’t used the term location value tax, Steve. I don’t know if you have, and if you have thoughts on it.

STEVE: My general thoughts are that I understand what you’re trying to get at with location value, but I tend to find that land value is the simpler way of explaining it both because it’s more directly contrastable against buildings in terms of what the impact of taxing each of them is, and their natural versus human created nature.

So I feel like land still works pretty well for those. It’s the “tax” part that is the difficult bit and that’s why Greg’s working with land value return. People sometimes they think that we’re talking about a new tax rather than restructuring existing taxes and that can be the big problem.

But sort of on all of this the message testing survey that we ran and that there’ll be a blog post coming out about soon. Russell Richie, I think is in here. He was heavily involved and has done a lot of the leg work on that. Keep an eye out for those because that’s kind of focusing on how you message this to people.

LARS: Because I live in a red state, I live in Texas where people are extremely anti-tax and have tried and failed to abolish property taxes twice. I found “universal building exemption” particularly effective in red states because it makes several things clear immediately. It is not a new tax. It is not a tax on land area. It is a tax on land value and it’s very clear how we are going to get there. We just reform the existing system with a new kind of exemption that is universal and on buildings. In other places, you might want different rhetoric, but it’s particularly effective when people’s hang-up is the word “tax.”

Q4: How to message that LVT won’t raise rents?

STEVE: There’s one here and there was a lot of discussion in the chat about a question was from Emmanuel Shorsk. What have you found most persuasive for arguing that rents won’t rise even if taxes go up? I think Lars linked to a short research brief that I wrote on that question and in that I attempted to explain it in three ways. One was kind of the intuitive sense which is that I think when people don’t believe that LVT won’t raise their rents, their intuition is that, oh, my landlord just passed all of the costs onto me. That’s how rent gets set and that’s why it’s going to happen. That I think is the biggest thing that you need to try and counter. The way that I do it in my written report is showing landlords are just going to charge you as much as they can get away with at all possible times.

LARS: (sarcastically) I mean, that’s why the landlord always gives you a rent decrease when their taxes go down, right?

STEVE: That was the other part of it. I talk about how when mortgage rates fall, nobody expects and nobody sees rents to go down at all. They’re not passing on there when their costs go down. We shouldn’t necessarily assume the opposite. Then I sort of stepped through the arcane economic theories around debt by loss and what that means for supply and how supply impacts rents and then some of the empirical research that backs that up. Those are my three approaches. I honestly think that the intuitive one is the most effective. I wouldn’t say that it’s a solved problem and sometimes it’s just a question of really understanding the person that you’re talking to and why they’re having that reaction. Greg, do you spot another question there?

Q5: LVT in Canada?

GREG: Yeah. I’m just noticing that there are Canadians in the chat and I think that we also had somebody from Commonwealth in the chat, but I included the link to Commonwealth. They’re doing good work on land value shifts in Canada and happy to connect folks there. I thought we had somebody in Commonwealth in the chat somewhere.

Q6: What about the “poor widow” who owns valuable land but is on a fixed income?

LARS: I do see a question about the “poor widow” argument.

This comes in a lot of places. This is about, okay, LVT is maximally efficient and it’s best for society as a whole, but there are some very politically sensitive and just emotionally sensitive cases where someone might be living on some very valuable land but would immediately get kicked off.

In Texas, this is a solved problem. I think it’s form 50-126. If you are a qualifying senior who is house poor and is at risk of losing your home due to rising property taxes, which would also be land value taxes or whatever, you can fill out a form and not pay another cent of property tax for the rest of your life.

The tax bill is deferred until death or until sale of the estate and it really deals with that security question straight up. Also, do the modeling. Is this an imaginary objection? Sometimes that house poor widow actually might possibly save after the shift. Maybe she would, maybe she wouldn’t, but you want to know whether it’s a real problem or not and not an imagined one. If not, there’s deferral precedent that directly deals with this without causing other distortionary problems down the road.

STEVE: For those who aren’t familiar, people will go, oh, that’s really unfair. There’s these old ladies in these large suburban homes that have put all of their savings into this for decades and decades and she’s on a fixed income and now you’re going to raise her taxes and that’s really unfair.

Actually, I think that the old widow is the cause of a lot of really bad tax policy because we tend to do a lot of weird little tweaks and carve outs and we don’t make the changes that we should be making because we’re worried about the transitional effects on populations like that. The thing that I sort of tend to talk about in those situations is we already have a lot of places have very extensive exemptions for retired homeowners. They’re pretty generous in a lot of places and they’ll kind of halve the tax bill from what it should be. In a lot of cases, they’re not going to be that affected anyway.

The other way around this is to say, and we always say in our policy work, you should keep the existing exemptions that you have for disadvantaged populations.

Another approach is to talk about how, well, yes, the old widow homeowner is a problem but as someone we should worry about, but what about the old widow renter? A lot of our policy doesn’t think about those types of people and those are the ones that land value tax really helps.

The other is that you should advocate for deferral programs, tax deferral programs for people who really can’t afford to pay their taxes. This is a policy where if you can’t pay your tax bill, the city will turn it into a lien against the property that just accumulates over time with a little interest rate on it and is payable when the property is sold.

So when you’re downsizing or when it becomes a part of your estate, that’s a really great way to ensure that the city is collecting the value of contribution to taxes that those retired homeowners should really be paying. They still use city services but to enable them to not have cash flow problems while they’re still living in the house. That’s a really good approach.

GREG: I’ll just add, it depends on the politics. Look, I’m sympathetic towards the elderly woman who has a higher tax burden—but they also own a $500,000 piece of land. I care a lot more about the low income folk who rents in the city and depending on the city, depending on where you’re doing advocacy, these will matter to differing effects.

One city I’m working in is just willing to accept it because they have a more populist rhetoric going on right now. But others, yeah, you’re going to have to build in exemptions etc. to sort of figure it out. But I think that, yeah, it really depends on the politics.

If there’s someone has one that’s not addressed, I’ll allow you to kind of unmute and jump in. But for those who need to go, we are running past the time now, I just want to say thank you to everybody for coming along and listening in. We really appreciate your time, on a Friday afternoon and we hope to hear from you and to be in touch for future events.

Be sure to subscribe to Progress & Poverty substack to be notified about the next LVT Landscape LIVE event!

Hi all!

Great event, thank you for hosting this. Just wanted to say I'm running for town council in "Gorham", not "Gore"

As an “efficient tax” LVT libertarian, I’d like to see advocacy of trading lower income tax for increased LVT. I believe that can be a bipartisan “win-win” selling point: Progressives get increased taxation of unearned wealth, while “conservatives” (whatever that means these days) get reduced taxes on work, savings and productive (i.e. non-land) investment.