In Memoriam: 125 Years Since Henry George

Excerpts from "Henry George: Unorthodox American" by Albert Jay Nock

A depression was on in the year 1864. In those days depressions did not go by their Latin name as a rule, except when people wanted to put on airs about them, but were called by the simple English name of hard times. This streak of hard times lay very heavily on the Pacific Coast. It was aggravated by a great drought that burned up the grain crop and pasturage, and killed most of the cattle on the ranches. There was no business in farming or ranching, industries were closed down, and commerce was at a dead halt.

At this time Henry George was twenty-five years old, living miserably in San Francisco, where, after a long struggle with misfortune, he had set up in a small way as a job printer. He had a wife and child, and his wife was shortly to give birth again. He could get no work, whether at printing or anything else, nor could he ask help from any one, for all the people he knew were wretchedly poor. Long afterward, speaking of this period, he said that as things went from bad to worse —

I came near starving to death, and at one time I was so close to it that I think I should have done so but for the job of printing a few cards which enabled us to buy a little corn meal. In this darkest time in my life my second child was born.

When this event happened he had no money, no food, no way to provide his wife with any care; he was alone in a bare lodging with a helpless suffering woman and a newborn baby. In a desperate state of mind he left the house and took to the last resort of the destitute.

I walked along the street and made up my mind to get money from the first man whose appearance might indicate that he had it to give. I stopped a man, a stranger, and told him I wanted five dollars. He asked what I wanted it for. I told him that my wife was confined and that I had nothing to give her to eat. He gave me the money. If he had not, I think I was desperate enough to have killed him.

Henry George had seen depressions before. When he was sixteen years old he saw one in Australia, where he lay in port for a month as foremast-boy on an old East Indiaman sailing out of New York for Melbourne and Calcutta. There he found times “very hard ashore, thousands with nothing to do and nothing to eat.” Two years later, in 1857, another depression threw him out of work in Philadelphia and sent him wandering to the Pacific Coast. After 1864, too, he was to be wrecked by still another depression, when the appalling hard times which followed the panic of 1873 broke up in succession two newspaper enterprises which had employed him, and he was once more set adrift and penniless.

Thus it was that the question occurred to him, why do these depressions happen? Why should there be any hard times? Nobody seemed to know. People took depressions as they took tuberculosis or typhoid, or as people in the Middle Ages took the bubonic plague, as something bound to happen, something that had to be put up with. They had always happened about once every so often, undoubtedly would always go on happening, and that was that. Yet in the nature of things there seemed no reason why they should happen. There was plenty of natural opportunity for everybody, plenty of everything that anybody could possibly need. The country was not poor and overpopulated — far from it. On the contrary, it was fabulously rich and had only a thin and straggling population. Nevertheless, every so often, with a strange regularity, hard times came around and vast masses of the people were left without work and without bread.

There must be some reason for this which no one had as yet discovered, and Henry George made up his mind that if he lived he would find out what it was.

Somehow he did manage to live. By one means or another he got over the peak of his greatest distress, and four years later, in the winter of 1868, he came from California to New York on an errand for a newspaper. He was then not quite thirty years old, and did not even yet have a dollar in his pocket that he could call his own. New York showed him something brand-new in his experience. Up to this time he had not been in a position to see any great show of inequality in the distribution of wealth. Life was simple in the Philadelphia of his boyhood days, and in the rough and new California of his youth one person lived much like another. But now, in the New York of 1868, he saw our western Palmyra in all the shoddy glory of its post-war period, and by all accounts it must have been a most dreadful sight, as repulsive as the pens of Dickens and George William Curtis pictured it. Shoddy riches, shoddy show, shoddy ideals and taste, shoddy people — and on the other hand, whole populations of troglodyte slum-dwellers living at an almost inconceivable depth of wretchedness and degradation.

Years afterward George said that here “I saw and recognized for the first time the shocking contrast between monstrous wealth and debasing want.” What was the cause of it? Again, nobody seemed to know. Like depressions and plagues, it was taken as part of the regular order of nature. It had always existed in large commercial and industrial centers, apparently it was bound always to exist, and it seemed to be just another one of the things that had to be put up with. There was no cure for it, so far as anybody knew. All that could be done was to take some of the curse off it by charity of one sort or another, and this was being done; in fact, it was beginning to be organized on a large scale, more lavishly perhaps than in any other country.

Nevertheless, George reasoned with himself, the thing had to have a cause, for nothing in nature ever happens without a cause. If that cause could be found, a cure might be found; but trying to deal with an effect without knowing anything about its cause would be mere fumbling in the dark. Here, then, was a second question, to which George pledged his lifetime for an answer. The first question was, what is the cause — not any superficial and apparent cause, but the true fundamental cause — of recurrent industrial depressions? The second question was, what is the true fundamental cause of the enormous inequality in the distribution of wealth?

George succeeded in answering these two questions to his own satisfaction while he was still a comparatively young man. This was the only success he ever had in his life; whatever else he touched failed. His one success, however, such as it was, led him through one of the strangest and most remarkable careers ever achieved in America, or for that matter, in the world.

In principle, as the politicians say, Henry George’s boyhood followed the course laid out by the storybooks that used to be written around the romance of American life. He did not exactly run away from school or run away to sea, but he did what came to the same thing. He served notice on his parents so firmly that they decided to let him have his own way. In the matter of schooling they perhaps thought it was just as well, for he seems to have been an all-round failure at any kind of book-learning. Between the ages of six and fourteen he tried his luck at four different schools, three of them private schools, and all of them first-rate as schools went in those days — and probably they went about as well then as they do now — but he was not worth his salt at any of them. He worried through the grammar grades, entered the high school, stuck at it almost half a year, and then struck his colors for good and all; he never had another day’s schooling.

He said afterward, rather austerely, that in his half year at the high school he “was idle, and wasted time.” He may have done so, but if he did it was exceptional, for as boy or man he was never shiftless or dissipated, but always a hard worker, with an uncommon amount of intellectual curiosity and scientific imagination. The worst of him was that he was hasty and impatient, and of a roaming, restless disposition which probably made his parents think that his best hope of getting any kind of discipline lay in the forecastle, and that since he wanted most of all to go to sea, it might be the best thing for him if they should let him go.

He went to sea in April, 1855, and his voyage on the Hindoo lasted a year and two months. She was an old wooden affair of 600 tons, in none too good shape, bought second-hand for a kind of tramp service after twenty-five years of hard wear and tear as an East Indiaman. She went out of New York in lumber for Melbourne, before heading to India. At the end of a year’s voyage, although looking forward eagerly to seeing his family and friends in Philadelphia, he wrote in his journal, “Oh, that I had it to go over again.”

The sea was not through with him, however. After the reunion with his people was over, the next thing was to cast about for something to do. His father got him a place with a printing firm to learn typesetting, where he stayed nine months, long enough to become a good journeyman compositor, and then quit in consequence of a row with his foreman. He had an offer from another firm, but the pay was nothing worth thinking of, and he did not take it. The depression of 1857 was coming on, and the few employers who had a place open were offering sweatshop terms. Finding that there was simply nothing doing in Philadelphia, he went to Boston, working his way on a topmast schooner that carried coal. There was nothing doing there either; so, on his return, attracted by reports of the fortunes being made on the Pacific Coast, he shipped on the lighthouse tender "Shubrick," which was going on the long voyage around the foot of South America, for service out of San Francisco.

While learning his new trade of typesetting in Philadelphia, he took lessons at night in penmanship and bookkeeping, with useful results. When his handwriting was fully formed, it was small and highly characteristic, but very clear and neat. Part of his father’s idea in having him learn to set type was to improve his spelling. Like some other great writers, notably Count Tolstoy, he could not spell. This branch of the mechanics of writing seems to call for some obscure kind of natural gift or aptitude, which George never had. He thought typesetting helped him a little, but it could not have helped him much, for he misspelled even the commonest words all his life.

While he was working at the case, too, there happened one of those trivial incidents that turn out to be important in setting the course of one’s life. He heard an old printer say that in a new country wages are always high, while in an old country they are always low. George was struck by this remark and on thinking it over, he saw that it was true. Wages were certainly higher in the United States than in Europe, and he remembered that they were higher in Australia than in England. More than this, they were higher in the newer parts than in the older parts of the same country — higher in Oregon and California, for instance, than in New York and Pennsylvania.

George used to say that this was the first little puzzle in political economy that ever came his way. He did not give it any thought until long after; in fact, he says he did not begin to think intently on any economic subject until conditions in California turned his mind that way. When finally he did so, however, the old printer’s words came back to him as a roadmark in his search for the cause of industrial depressions, and the cause of inequality in the distribution of wealth.

Like all those who anticipated Horace Greeley’s classic advice to young men, Henry George went west for quick money and plenty of it. He had no notion of mining, but of prospecting; that is to say, his idea was not to work a mine, but to pick up mineral land, and then either sell it or have it worked on shares with somebody who would do the actual mining. In short, as he would have phrased it in later years, his idea was to make his fortune by appropriating the economic rent of natural resources, rather than by applying labor to them.

But there were too many ahead of him who had the same idea. Although the mineral region of California is as large as the British Isles, he found that these lively brethren had pre-empted every foot of it. He tried Oregon with no better luck, living meanwhile as best he could, by all sorts of expedients — farm work, tramping, storekeeping, peddling — and when he finally went back to his trade, he did it as only another makeshift, for the vision of sudden wealth still haunted him. In a letter to his sister he says that in a dream the night before he was “scooping treasure out of the earth by handfuls, almost delirious with the thoughts of what I would now be able to do, and how happy we would all be;” and he adds wistfully that he supposes he dreamed all this as starving men dream of splendid feasts, or as desert wanderers dream of brooks and fountains.

His trade kept him only very precariously, for times were not easy even then, and there was no great demand for printing or printers. He got a job with one newspaper, then with a second, where, he says, “I worked until my clothes were in rags and the toes of my shoes were out. I slept in the office and did the best I could to economize, but finally I ran in debt thirty dollars for my board bill.” He left this job and went adrift again; and then, with no work, no prospects, and with but one piece of money in his pocket, he made a runaway match with a young Australian girl named Annie Fox.

They married not wisely — there is no doubt about that — but wonderfully well, for their marriage appears to have remained perfect until his death in 1897 dissolved it. Balzac called attention to a little-known truth when he said that “a great love is a masterpiece of art,” and there are probably about as few really first-rate artists in this field as in any other. Moreover, a masterpiece in this field of art must be a collaboration, and the chance of two first-rate artists finding each other is extremely small, practically a matter of pure luck. A Daphnis in any age may wander over the whole earth without meeting a Chloe, and a Cynthia may survey whole legions of men and never see a Claudius. George’s meeting with his wife was almost the only piece of sheer good luck he ever had, but it was a great one. On the night of the twelfth of October, 1883, he wrote this note, and put it by her bedside for her to find next morning:

It is twenty-three years ago tonight since we first met, I only a month or two older than Harry, and you not much older than our Jen. For twenty-three years we have been closer to each other than to anyone else in the world, and I think we esteem each other more and love each other better than when we first began to love. You are now ‘fat, fair and forty,’ and to me the mature woman is handsomer and more lovable than the slip of a girl whom twenty-three years ago I met without knowing that my life was to be bound up with hers. We are not rich — so poor just now, in fact, that all I can give you on this anniversary is a little love-letter — but there is no one we can afford to envy, and in each other’s love we have what no wealth could compensate for. And so let us go on, true and loving, trusting in Him to carry us farther who has brought us so far with so little to regret.

George now committed himself to newspaper work, moving from paper to paper in all kinds of capacities, from typesetter to editor and part owner, and by 1868 he had become prosperous enough to start a bank account. His editorial career was very spirited; he was in one row or another all the time, and while it may be said that in his treatment of State and local grievances he was on the popular side, he always lost. He made things lively for the Associated Press news monopoly, but though he got an anti-monopoly bill through the legislature, all that happened was that the monopoly broke his paper. He fought the Wells-Fargo express monopoly, and lost again — too much money against him. He attacked the Central Pacific’s subsidies, and ran for the Assembly as a Democrat on that issue, but again there was too much money on the other side — the Democrats lost, the Central Pacific quickly bought up his paper, merged it with another, and George was out.

So it went. Every turn of public affairs brought up the old haunting questions. Even here in California he was now seeing symptoms of the same inequality that had oppressed him in New York. “Bonanza kings” were coming to the front, and four ex-shopkeepers of Sacramento, Stanford, Crocker, Huntington, and Hopkins, were laying up immense fortunes out of the Central Pacific. The railway was bringing in population and commodities, which everybody thought was a good thing all round, yet wages were going down, exactly as the old printer in Philadelphia had said, and the masses were growing worse off instead of better.

Still, though his two great questions became more and more pressing, he could not answer them. His thought was still inchoate. He went around and around his ultimate answer, like somebody fumbling after something on a table in the dark, often actually touching it without being aware that it was what he was after. Finally it came to him in a burst of true Cromwellian or Pauline drama out of “the commonplace reply of a passing teamster to a commonplace question.” One day in 1871 he went for a horseback ride, and as he stopped to rest his horse on a rise overlooking San Francisco Bay —

I asked a passing teamster, for want of something better to say, what land was worth there. He pointed to some cows grazing so far off that they looked like mice, and said, ’I don’t know exactly, but there is a man over there who will sell some land for a thousand dollars an acre.’ Like a flash it came over me that there was the reason of advancing poverty with advancing wealth. With the growth of population, land grows in value, and the men who work it must pay more for the privilege.

Yes, there it was. Why had wages suddenly shot up so high in California in 1849 that cooks in the restaurants of San Francisco got $500 a month? The reason now was simple and clear. It was because the placer mines were found on land that did not belong to anybody. Any one could go to them and work them without having to pay an owner for the privilege. If the lands had been owned by somebody, it would have been land-values instead of wages that would have so suddenly shot up.

Exactly this was what had taken place on these grazing lands overlooking San Francisco Bay. The Central Pacific meant to make its terminus at Oakland, the increased population would need the land around Oakland to settle on, and land values had jumped up to a thousand dollars an acre. Naturally, then, George reasoned, the more public improvements there were, the better the transportation facilities, the larger the population, the more industry and commerce — the more of everything that makes for “prosperity” — the more would land values tend to rise, and the more would wages and interest tend to fall.

George rode home thoughtful, translating the teamster’s commonplace reply into the technical terms of economics. He reasoned that there are three factors in the production of wealth, and only three: natural resources, labor, and capital. When natural resources are unappropriated, obviously the whole yield of production is divided into wages, which go to labor, and interest, which goes to capital. But when they are appropriated, production has to carry a third charge — rent. Moreover, wages and interest, when there is no rent, are regulated strictly by free competition; but rent is a monopoly-charge, and hence is always “all the traffic will bear.”

Well, then, since natural resource values are purely social in their origin, created by the community, should not rent go to the community rather than to the Individual? Why tax industry and enterprise at all — why not just charge rent? There would be no need to interfere with the private ownership of natural resources. Let a man own all of them he can get his hands on, and make as much out of them as he may, untaxed; but let him pay the community their annual rental value, determined simply by what other people would be willing to pay for the use of the same holdings. George could see justification for wages and interest, on the ground of natural right; and for private ownership of natural resources, on the ground of public policy; but he could see none for the private appropriation of economic rent. In his view it was sheer theft. If he was right, then it also followed that as long as economic rent remains unconfiscated, the taxation of industry and enterprise is pure highwaymanry, especially tariff taxation, for this virtually delegates the government’s taxing power to private persons.

George worked out these ideas in a tentative way in a forty-eight page pamphlet with the title, “Our Land and Land Policy, National and State,” which did not reach many readers, but added something to his reputation as a tribune of the people. The subject mulled in his mind through five years of newspaper work, at the end of which he lost his paper and was once more on the ragged edge. He had begun a magazine article on the cause of industrial depressions, but was dissatisfied with it — one could do nothing with the topic in so little space. What was needed was a solid treatise which should recast the whole science of political economy.

He felt that he could write this treatise, but how were he and his family to live meanwhile? He had used his influence on the Democratic side in the last State campaign, and had been particularly instrumental in selecting the governor; so he wrote to Governor Irwin, asking him “to give me a place where there was little to do and something to get, so that I could devote myself to some important writing.” The governor gave him the State inspectorship of gas meters, which was a moderately well-paid job, and a sinecure. This was in January, 1876; and in March, 1879, he finished the manuscript of a book entitled Progress and Poverty: an Inquiry Into the Cause of Industrial Depressions, and of Increase of Want With Increase of Wealth; the Remedy.

No one would publish the book, not so much because it was revolutionary (though one firm objected to it emphatically on that ground) but because it was a bad prospect. No work on political economy, aside from textbooks, had ever sold well enough either in the United States or England to make another one attractive. Besides, the unparalleled depression of the ’seventies was making all the publishing houses sail as close to the wind as they could run. Logically, a book on the cause of hard times ought to interest people just then, but book buyers do not buy by logic, and publishers are aware of it.

By hook or crook George and his friends got together enough money to make plates for an author’s edition of five hundred copies; George himself set the first few sticks of type. At three dollars a copy he sold enough of these almost to clear the cost; and presently the firm of Appleton, who had rejected the manuscript, wrote him that if he would let them have his plates, they would bring out the book in a two-dollar edition; and this was done.

It fell as dead as Caesar, not even getting a competent press notice in America for months. George sent some complimentary copies abroad, where it did rather better. Emile de Laveleye praised it highly in the Revue Scientifique; it was translated into German, and its reviews, as George said, were “way up.” Some sort of sale began in March, 1880, with a brilliant review in the New York Sun, which was followed by more or less serious treatment in the Eastern press generally; but it amounted to almost nothing.

George came to New York on the heels of his book, selling out what little he possessed in California. During his first year there, while his cherished book lay dead, he lived in obscurity, wretchedly poor; and then the time came when he could take advantage of something on which the eyes of the whole English-speaking world were fixed — the Irish rent-war.

Ireland at that time was front-page news on every paper printed in the English language. Parnell and Dillon crossed the ocean, spoke in sixty-two American cities, addressed the House of Representatives, and took away a great fund of American dollars wherewith to fight the battles of the rack-rented Irish tenant. They were followed by the best man in the movement, Michael Davitt, who came over late in 1880 to tend the fire that Parnell and Dillon had kindled. George met him and got him “under conviction,” as the revivalists say, and then wrote a pamphlet entitled “The Irish Land Question; what it involves, and how alone it can be settled.”

From that moment Henry George was, in the good sense of the term, a made man. The pamphlet was a masterpiece of polemics, a call to action, and a prophecy, all in one. Published simultaneously in America and England, it had an immense success. George was amazed at the space it got in the Eastern papers. “The astonishing thing,” he wrote, “is the goodness of the comments... I am getting famous, if I am not making money.” It is hard to see how a man who had ever done a day’s work on a newspaper could write in that unimaginative way. With Irish influence as strong as it was on the Eastern seaboard, and with every Irishman sitting up nights to curse the hated Sassenach landlords and their puppet government, how could the newspaper comments not be good? The Eastern papers simply knew which side their bread was buttered on.

A rabble of charmed and vociferous Irish closed around the simple-hearted pamphleteer, probably not troubling themselves much about his philosophy of the Irish land question, but nevertheless all for him. He was against the government and against the landlords, and that was enough. In this they were like the vast majority of readers who were led to peck at Progress and Poverty because they had heard that the book voiced their discontent; probably not five per cent of them read it through, or were able to understand what they did read, but they were all for it nevertheless, and all for glorifying Henry George. The American branch of the Land League immediately put George on the lecture platform, and when the Irish troubles culminated in the imprisonment of Davitt, Dillon, Parnell, and O’Kelly, an Irish newspaper published in New York sent him to the seat of war as a correspondent.

He reached Dublin, dogged by secret service men, and gave a public lecture with such effect that his audience went fairly wild. He wrote a friend that he had “the hardest work possible” to keep the crowd from unharnessing his cab-horse and dragging his carriage through the streets to his hotel. His reports to the Irish World got wide distribution. When he crossed to England, interest opened many doors to him outside political circles, and curiosity opened many more. He dined with most of the lions of the period, Besant, Herbert Spencer, Tennyson, Justin McCarthy, Wallace, Browning, Chamberlain, John Bright, and made an excellent impression. He wrote his wife that he could easily have become a lion himself if he had liked, but he thought it best to keep clear of all that sort of thing.

All this celebrity was a great lift for Progress and Poverty. The book suddenly became an international best seller. The London Times gave it a five-column review which made its fortune in all the British possessions; the review came out in the morning, and by afternoon the publishers had sold out every copy in stock. When a new edition was rushed out, one house in Melbourne ordered 1300 copies, and 300 were sent to New Zealand. George was invited everywhere, banqueted everywhere, asked to speak on all sorts of occasions, reported everywhere; and when he left the British Isles for home, he was perhaps the most widely talked-of man in either hemisphere.

For the next two years George lived before the populace, speaking and writing incessantly, and directing the development of his doctrine into a distinctly political character. At that time the press was much more an organ of opinion than it is now, much freer and more forceful, so that his writings were in demand. Even a popular publication like Leslie’s asked him for a series on the problems of the time, while at the other end of the scale the North American Review made him a proposal to start a straight-out political and economic weekly under his editorship.

Yet though his method was that of the evangelist, he did not adopt the tactics of the demagog or the practical politician. He was probably the most effective public speaker of his time — The London Times thought he was fully the equal of Cobden or of Bright, if not a little better — but he never took advantage of an audience, or flattered the galleries, or left the smallest doubt of where he stood and what was in his mind. When, for example, somebody introduced him in a maudlin way to a working-class audience as “one who was always for the poor man,” George began his speech by saying, “Ladies and gentlemen, I am not for the poor man. I am not for the rich man. I am for man.”

In fact, it soon became apparent that his hell-raising was raising as much hell with his supporters and potential friends as with his enemies. Like Strafford of old, he was for “thorough,” no matter whose head came off or whose toes smarted. All the Irish leaders, even Davitt, cooled off to the freezing point when they found that he was down on the Kilmainham treaty and dead against any compromise on the issues of the rent-war, or any watering down of the program of restoring one hundred per cent of Ireland’s land to one hundred per cent of Ireland’s people. The Socialists were not unfriendly at first, and some of George’s followers thought a sort of working alliance with them might be vamped up for political effect, but when George attacked their doctrine of collectivism and statism, they most naturally showed all their teeth. George held with Paine and Thomas Jefferson that government is at best a necessary evil, and the less of it the better. Hence the right thing was to decentralize it as far as possible, and reduce the functions and powers of the state to an absolute minimum, which, he said, the confiscation of rent would do automatically; whereas the collectivist proposal to confiscate and manage natural resources as a state enterprise would have precisely the opposite effect — it would tend to make the state everything and the individual nothing.

George was moreover the terror of the political routineer. When the Republicans suddenly raised the tariff issue in 1880 the Democratic committee asked him to go on the stump. They arranged a long list of engagements for him, but after he made one speech they begged him by telegraph not to make any more. The nub of his speech was that he had heard of high-tariff Democrats and revenue-tariff Democrats, but he was a no-tariff Democrat who wanted real free trade, and he was out for that or nothing; and naturally no good bi-partisan national committee could put up with such talk as that, especially from a man who really meant it.

Yet, on the other hand, when the official free-traders of the Atlantic seaboard, led by Sumner, Godkin, Beecher, Curtis, Lowell, and Hewitt, opened their arms to George, he refused to fall in. His free-trade speeches during Cleveland’s second campaign were really devoted to showing by implication that they were a hollow lot, and that their idea of free trade was nothing more or less than a humbug. His speeches hurt Cleveland more than they helped him, and some of George’s closest associates split with him at this point. In George’s view, freedom of exchange would not benefit the masses of the people a particle unless it were correlated with freedom of production; if it would, how was it that the people of free-trade England, for example, were no better off than the people of protectionist Germany! None of the official free-traders could answer that question, of course, for there was no answer. George had already developed his full doctrine of trade in a book, published in 1886, called Protection or Free Trade — a book which, incidentally, gives a reader the best possible introduction to Progress and Poverty.

He laid down the law to organized labor in the same style, showing that there was no such thing as a labor-problem, but only a monopoly-problem, and that when natural-resource monopoly disappeared, every question of wages, hours, and conditions of labor would automatically disappear with it. The political liberal got the hardest treatment of all. George seems to have regarded him as the greatest obstruction to social progress — an unsavory compound, half knave, half fool, and flavored odiously with “unctuous rectitude.” When John Bright, the Moses of Liberalism, followed George on the rostrum at Birmingham, calling his proposals “the greatest, the wildest, the most remarkable ... imported lately by an American inventor,” all George could find to say was (in a private letter) that “the old man is utterly ignorant of what he is talking about” — which was strictly true; and of Frederic Harrison’s lectures at Edinburgh and Newcastle he said only that “his is the very craziness of opposition, if I can judge by the reports.”

Thus intellectually he was out with every organized force in the whole area of discontent; out with the Socialists, out with the professional Irish, the professional laborites, professional progressivism, liberalism, and mugwumpery. His sympathies and affections however were always with the rank and file of revolt against the existing economic order; his heart was with all the disaffected, though his mind might not be entirely with them. This being so, the two years following his first visit to England fastened upon him the stigma of a mere proletarian class-leader whose principles and intentions were purely predatory. As Abram S. Hewitt most unscrupulously put it, his purpose was no more than “to array working men against millionaires.”

Then at the end of these two years there happened the one thing needful to copper-rivet this reputation and make it permanent. When the labor unions of New York City decided to enter the mayoralty campaign of 1886, they looked to George as the best vote-getter in sight, and gave him their nomination. With this, whatever credit he may have had in America as an economist and philosopher vanished forever, leaving him only the uncertain and momentary prestige of a political demagogue, an agitator, and a crank.

George had misgivings, not of defeat but of discredit in his role of candidate, but they came too late. The course he had chosen years before led straight to the quicksand of practical politics, and now his feet were in it. He temporized with the nomination, demanding a petition signed by thirty thousand citizens pledged to vote for him, which was immediately forthcoming — and there he was!

The campaign was uncommonly bitter. The other candidates were Hewitt and Theodore Roosevelt, and their methods bore hard on George in ways that Hewitt, at any rate, must somewhat have gagged at, for he was a man of breeding — still, he lent himself to them. It was easy to vilify George, because the allegation that he was a sheer proletarian leader was true enough, as far as this campaign went; he was, officially and by nomination, a labor candidate. Some among his supporters, of course, understood his ideas and purposes and believed in them, but these were relatively few; the majority were mere Adullamites. Hewitt won the election nominally — in all reasonable likelihood he was counted in — but George’s vote was so large that the New York Times saw in it “an event demanding the most serious attention and study;” while the St. James Gazette of London, in a strong grandmotherly vein, advised “all respectable Americans to forget the trumpery of party fights and political differentism, and face the new danger threatening the commonwealth.”

As far as George was concerned, there was no need of this warning, for his day in politics was done. This one campaign was the end of him. He was no longer a man to be feared or even reckoned with. To those on the inside of practical politics, he was henceforth hopelessly in the discard as the worst of all liabilities, a defeated candidate. To America at large, he was only another in the innumerable array of bogus prophets and busted spellbinders. Before a year was over, George had dropped into a historical place amidst all this ruck, from which he has never emerged, as just one more exploded demagogue. He ran for a state office in 1887, but got little more than half the votes in New York City, his stronghold, that he had got in the mayoralty campaign only a year before.

The last ten years of his life were devoted largely to a weekly paper, the Standard, in which he continued to press his economic doctrine, but it amounted to very little. He revisited England, where he found his former popularity still holding good. He also made a trip around the world, and was received magnificently in his former home, California, and in the British colonies. His main work during this period, however, was writing his Science of Political Economy, which his death interrupted; fortunately not until it was so nearly finished that the rest of his design for it could be easily filled in.

In this period, too, his circumstances, for the first time in his life, were fairly easy. He had received some small gifts and legacies, and latterly a couple of well-to-do friends saw to it that he should finish his work without anxiety. It is an interesting fact that George stands alone in American history as a writer whose books sold by the million, and as an orator whose speech attracted thousands, yet who never made a dollar out of either.

His death had a setting of great drama or of great pathos, according to the view that one chooses to take of it. The municipal monstrosity called the Greater New York was put together in the late ’nineties, and some of George’s friends and associates, still incorrigibly politically minded, urged on him the forlorn hope of running as an independent candidate for the mayoralty in 1897. Seth Low, then president of Columbia University, and Robert van Wyck, who was the impregnable Tammany’s candidate, were in the field — the outcome was clear — yet George acceded. It is incredible that he could have had the faintest hope of winning; most probably he thought it would be one more chance, almost certainly his last, to bear testimony before the people of his adopted city with the living voice.

He had had a touch of aphasia in 1890, revealing a weakness of the blood vessels in his brain, and his condition now was such that every physician he consulted told him he could not possibly stand the strain of a campaign; and so it proved. He opened his campaign at a rapid pace, speaking at one or more meetings every night, nearly always with all his old clearness and force. Three weeks [editor's note: 3 days] before election he spoke at four meetings in one evening, and went to bed at the Union Square Hotel, much exhausted. Early next morning his wife awoke to find him in an adjoining room, standing in the attitude of an orator, his hand on the back of a chair, his head erect and his eyes open. He repeated the one word “yes” many times, with varying inflections, but on becoming silent he never spoke again. Mrs. George put her arm about him, led him back to his bed with some difficulty, and there he died.

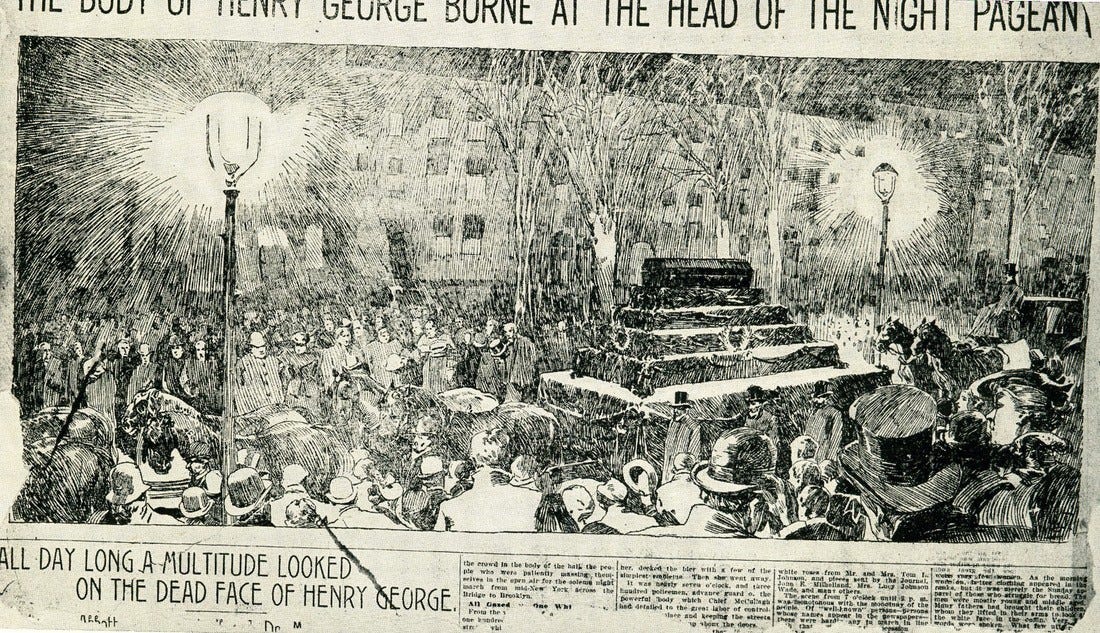

Henry George died on October 29th, 1897.