Essay Contest 3rd Place: The Georgist Jubilee

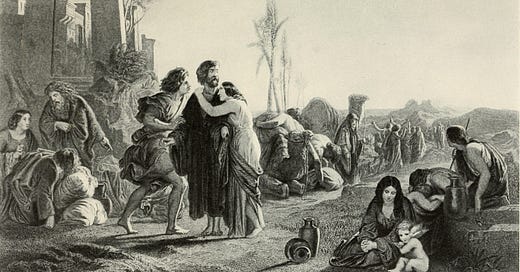

The revelation of the Mosaic Law reminds us that man is but a steward of the land which he momentarily occupies; our responsibility is to use it justly.

[Note from the Editor: Our annual essay contest has now been closed, and we’re back with the winners. We’ll be publishing them in reverse order, with 1st place being published last. Thanks to everyone who participated! We received many excellent submissions, and we look forward to doing this again next year.]

For thousands of years, faithful readers of the Hebrew Bible have been struck by one particular economic concept: that of the year of Jubilee. Jubilee was a land-use ritual that the biblical book of Leviticus instructs faithful Israelites to follow every fifty years, a practice that would serve as a kind of a "reset" to economic life. On the jubilee year, all farmland returned to the extended family who historically owned the land, with all individual debts incurred on the land cleared from their family's balance sheet. The land was also supposed to lie at rest, with the people trusting that God would produce a good harvest without their best efforts at cultivation.

As you might expect, this practice of Jubilee was complex and multilayered: it was crafted as a land-use ritual with four main social principles for what purpose land was supposed to serve:

First, it provided for family stability. Jubilee ensured that no family would ever be displaced from their family farm because the land rights stayed with the ancestral community and were returned to them every 50 years. As a result, familial networks built over centuries would not be disrupted by famine or economic hard times. If speculators could swoop in and buy property from struggling families in a difficult economic time, their family members had an opportunity to step in and buy them out. But even if no family member could perform this redemptive role, Jubilee ensured that the land would eventually return the land to their children or grandchildren.

Second, the Jubilee also functioned as a crucial part of the social safety net. The safety net didn't come through redistribution but pre-distribution: the land was equally allocated to tribes from the beginning, and Jubilee maintained that. Family units could then lease their agricultural land in ancient Israel for any length of time up to the next Jubilee if they needed the cash. But they would be economically secure in knowing they would not permanently lose access to agricultural land and, thus, economic opportunity. Moreover, in a society where the primary economic resource was agricultural, Jubilee ensured that if the land returned a bountiful harvest, all families would share in the bounty, and no one would go hungry.

Third, Jubilee was designed to support long-term economic growth. Ancient Israel was called in Genesis 1 to "Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it." Economic growth and prosperity were necessary for the survival of society; otherwise, they would be vulnerable to famine (not enough food) or war (not enough people). By giving all families of the community the ability to own and work the land, they ensured that the incentives were to maximize the land and the harvest. Jubilee was also not a wholescale redistribution of wealth. Notably, urban dwellings in walled cities were exempt from the Jubilee, presumably because they were built with human hands and not appropriated from God's creation.

Fourth, Jubilee was designed to be ecologically sustainable by giving the land a chance to rest from agricultural production. The people were asked to trust that even without human labor, the land would still produce enough food to keep all fed. God promised he would provide while giving land time to heal from human work and to see the soil had a chance to replenish.

But while these four social and economic principles were core to the Jubilee, they were not its primary purpose. In the Hebrew Bible, the land is, first and foremost, a gift from God. Israel's land was not earned by their hard work or conquest; the land was a creation of God, gifted to them by God. Scholar and ethicist Christopher Wright calls this God's gift of the land the "overarching theme" of the scripture's retelling of Israel's history. The ritual of Jubilee was primarily a theological reminder of God's grace. Leviticus 25 describes it thus:

Consecrate the fiftieth year and proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you; each of you is to return to your family property and to your own clan… The land must not be sold permanently, because the land is mine, and you reside in my land as foreigners and strangers.

From this perspective, Israel's land never truly belonged to their ancestral tribes: tribes were the stewards of the land, compelled by God's generosity to make the most of the land since it was under His ownership. Israel believed it had a special covenant relationship with God, and while they did nothing to earn this relationship with God, they were required to work to be faithful to God's instructions for their people. Christopher Wright describes Israel's practice of Jubilee and other economic rituals as a "spiritual thermometer" that revealed the state of the spiritual vitality of the relationship between the nation and their God. After all, God is explicitly clear about the threat of exile from the land if these land-use rituals are not followed as instructed.

Jubilee was meant to be a strange and radical practice for all readers. Modern readers will almost certainly find strange the notion of a God being so intimately involved in a nation's land use. Ancient readers would have found it radical that the king was not the absolute and sole ruler of the land, as they were in the surrounding empires of Egypt and Babylon. Jubilee is so strange that many historians and scholars have dismissed the idea that the ancient Israelites could have ever practiced Jubilee.

Regardless of whether this speculation is true, the Hebrew Bible clearly shows that Israel failed to live up to God's commandments. Furthermore, any practice of Jubilee that did happen seems to have been an exception, for we see prophet after prophet speaking about the injustice of the rich exploiting the poor and expropriating their land. Ancient Israel's moral low point was likely best illustrated in 1st Kings 21, where the corrupt King Ahab and Queen Jezebel succeed in stealing the productive and valuable vineyard of Naboth, who is scapegoated and executed. Thus, the reader is not surprised when Israel eventually finds itself exiled, no longer trusted to steward God's gift of the land.

The Failure of America's Land Use

Modern America is quite a different cultural world than ancient Israel. Our economy is vastly different, complex and multilayered, and far less dependent on access to agricultural land. In 2020, less than 1% of our GDP and less than 10% of our exports were attributable to agricultural production. Our culture is also vastly different: we are a pluralistic mix of people of all religious, moral, and philosophical foundations. But one thing has historically united all Americans: a belief that we possess near-absolute property rights when it comes to our land. This belief is a far cry from ancient Israel's view that God was the valid land owner, and the people were mere stewards.

Some may see this individual ethos as more progressive, and not without good reasons. A critical reason for American prosperity has been that individuals can trade and sell capital and labor freely, act entrepreneurially, and reap the rewards of those decisions. American prosperity has led to immense technological and scientific progress, pushing barriers previously inconceivable. This progress has been felt worldwide, as humanities have made real progress against our worst foes: poverty, plague, and violence. One could reasonably argue that we are the more successful nation-state in economic history.

Yet, for all of our progress, we are still troubled by this simple economic problem of land. The philosophy of individual land ownership has always sat uneasily in the American tradition since land ownership becomes a kind of de facto monopoly over that economic resource. John Locke, maybe the most influential philosopher on the individual rights central to the American experiment, struggled profoundly with the concept of private land ownership. Locke reasoned that private land ownership was necessary, but he also maintained that this was only justified if you worked to improve the land and only if one left "enough" for others.

In reality, America never honestly tried to resolve this tension in Locke's conclusion. Our land's history has been far from just; the very existence of the United States required the mass displacement of America's indigenous people from their land. Today, many reside on reservations located in regions with the most minimal access to economic opportunity anywhere in the US. Also, in American history, land ownership was explicitly and implicitly denied to many through American history based on race and class. The first half of the 20th century saw explicitly racist convents, and zoning prevented African Americans from becoming property owners in many neighborhoods. At the same time, redlining practices undermined the value of the properties they could buy. Places as diverse as Santa Monica, California, and Helena, Montana, have a shared history of using a variety of tactics to displace their African American residents. Likewise, speculators and absentee owners bought up the most valuable land in rural Appalachia. In 1810, it was estimated that "93 percent of land in present-day West Virginia was held by absentee owners," ensuring that economic returns of extracting industries like mining and logging flowed mainly to the landholders and not to the state's residents. Still today, six West Virginia counties (all in coal country) have more than 50% of their land owned by their ten largest landholders.

The situation is just as bad in our country's most productive cities. The geography where you grow up in America remains one of the best predictors of socioeconomic success in our society, meaning that vast amounts of our country's opportunity gap can be directly tied to land markets. Where I live in Los Angeles, economic inequality has grown tremendously in recent years, as wealthy landowners have used government policies to limit access to housing in our neighborhoods with the most economic opportunity. These wealthy landowners have also crafted tax rules like proposition 13 to ensure that they pay a fraction of the taxes on their property compared to their neighbors. Meanwhile, residents of my neighborhood of East Los Angeles find themselves under increasing pressure to move, as rents go up faster than wages, and they cannot benefit from the city's economic prosperity. If they move, they are forced to live farther and farther out into the desert, increasing the environmental and ecological pressures on our already stressed land.

This history makes one question: what good is building the most sophisticated economic engine in world history if we so severely fall short of good land-use policy? In these ways, modern America is not that different from ancient Israel. With all of our progress, we have still not found a way to practice land-use policies that benefit all in our society. Land in America continues to enrich some while immiserating others; by definition, no new land has been created. If the Hebrew Bible's prophets were around today, they would not have kind words to say about how we used land.

Where does this leave the millions of Americans like myself who consider the Jubilee part of God's sacred story and text? Since we believe that our economic practices as people of faith are intimately connected to our religious faithfulness, how can we advocate that our society enact more just land use policies? After all, faithful application of these rituals in a modern does not involve literally re-enacting the Jubilee in 2022 America. Instead, it means trying to take the values conveyed through the paradigm and apply them in today's context using policies that have empirical evidence that they can achieve those ends. So what does a just land-use policy look like?

A Jubilee for Today

Henry George rose to prominence in the late 1800s as a social critic who questioned the role of land in distorting the gains from American prosperity. The industrial revolution in America had made many making some fabulously wealthy while many others were still in grinding poverty. George was not a religious man; he described himself as a "deistic humanitarian." But even so, he found common ground within the Christian vision of the world that primarily sees land as a gift; not something humans can create. George, therefore, thought that government policy should capture the value of land and return that value to society. This was where the notion of land value taxation was born. George believed that landowners did nothing to "earn" their rent. However, George was not arguing for a whole redistribution of wealth: he thought those that developed innovative uses (houses, commercial space) should not be taxed for these improvements because they were forms of capital built from their efforts. George did not think the city's fundamental problem was the capitalist's incentives; instead, he felt the fundamental problem was with the landlord's incentive.

Ironically, George's idea never gained traction in America and, even more tragically, never gained traction in religious circles. This has been a tragic missed opportunity. Nevertheless, George’s tax ideas is a convenient tool to improve the economic output and the fairness of our nation's land use, especially in our urban environments. George's ideas are also a tangible way to apply the principles of the Jubilee in our modern economy.

Modern America flips the pattern of land from ancient Israel: our most significant economic engine lies in our cities, which are best understood as large labor markets that create economic opportunity through the concentration of jobs and industry. Landowners benefit from this economic engine even if they contribute nothing to it, simply by the good fortune of owning the "right' land. Georgism is the perfect compliment to the growing pro-housing movement that argues for loosening burdensome land-use restrictions in our American cities. First, creating incentives to redevelop ensures that the city keeps growing and expanding instead of stagnating. Land taxes ensure that the gains from that new housing are spread widely in society by investing those rises in land values in education and mobility infrastructure that lower-income residents need to participate in that modern city economy fully. And finally, by reducing the pressures that are currently leading to the displacement of low-income households, land value taxes can keep families together. And by keeping those families in our cities, the policy also takes the pressure off of more ecologically sensitive land where low-income residents would otherwise be displaced.

Ultimately, some of us have a more profound hope that goes beyond the economy. By working to see the principles of the Jubilee implemented through Georgist methods, we are actively humbling ourselves to remember that whatever land we own, we are but stewards for a time and a moment. And by working to ensure that government policy ensures the land serves the purposes of God, we hope that, in some mysterious way, we might yet see God’s justice roll down like waters and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.

Thomas Irwin works for Servant Partners, a faith-based non-profit in Los Angeles focused on various economic development initiatives. He is also a Southern California Association of Government’s Housing Leadership Academy member and helped start the Faith in Housing Coalition, a group that educates pastors and church leaders in Southern California about the housing crisis and how to seek housing justice in their city. He also is an avid pontificator on his own SubStack. He lives in East Los Angeles with his wife and son.

Samuel told all the words of the LORD to the people who were asking him for a king.

He said, "This is what the king who will reign over you will do: He will take your sons and make them serve with his chariots and horses, and they will run in front of his chariots.

Some he will assign to be commanders of thousands and commanders of fifties, and others to plow his ground and reap his harvest, and still others to make weapons of war and equipment for his chariots.

He will take your daughters to be perfumers and cooks and bakers.

He will take the best of your fields and vineyards and olive groves and give them to his attendants.

He will take a tenth of your grain and of your vintage and give it to his officials and attendants.

Your menservants and maidservants and the best of your cattle [2] and donkeys he will take for his own use.

He will take a tenth of your flocks, and you yourselves will become his slaves.

When that day comes, you will cry out for relief from the king you have chosen, and the LORD will not answer you in that day."

Thank you. This is a nice article and it is good to be reminded of the jubilee in the Old Testament. It resonates with other ancient customs that hold that private property is the beginning of social injustice, through averice. To most ancient societies ownership of the land is incomprehesible. It simply cannot be. So its beginning had to be through force.