Abundance and Anti-Monopoly: The Legacy of Tom Johnson

A Cleveland mayor from the Gilded Age shows how to synthesize two clashing movements

Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s book Abundance has ignited a debate about the value of cutting red tape. For many critics, cutting regulations on government projects bears the taint of neo-liberalism, sounding suspiciously like cutting regulations on private business. But visions of decisive government action are more in line with New Deal liberalism. Movements for economic reform that began with populism in the 1880s and culminated with the New Deal were disparate, with few commonalities. But if there was one stand that ran throughout, it was that courts and cumbersome process impeded democracy and empowered special interests. A more responsive government that could build the things citizens needed was widely accepted as one of the most important prescriptions for saving the United States from the global drift toward fascism. Tom Johnson united anti-monopoly and abundance and serves as a model for what an authentically anti-monopolist abundance movement might look like.

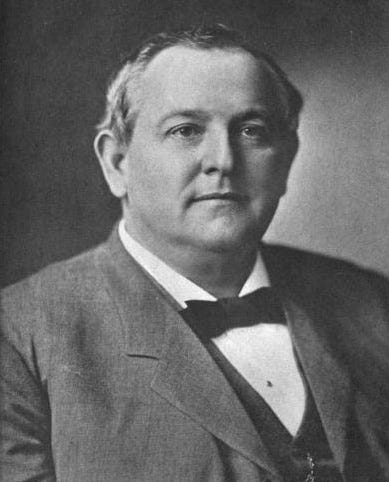

In 1905, the muckraker Lincoln Steffens branded Tom Johnson, the Mayor of Cleveland, “The Best Mayor of the Best Governed City in the United States.” Johnson won the title by building a new city. During his eight years in office, he paved as many roads, built streetlights, and dug nearly as many sewers as had been built in the entire history of the city up to his eight years in office. As a democrat, he became the longest serving mayor the republican-leaning city had ever had, and his lieutenant, Newton Baker, succeeded him in the most lopsided victory the city had ever given a mayoral candidate.

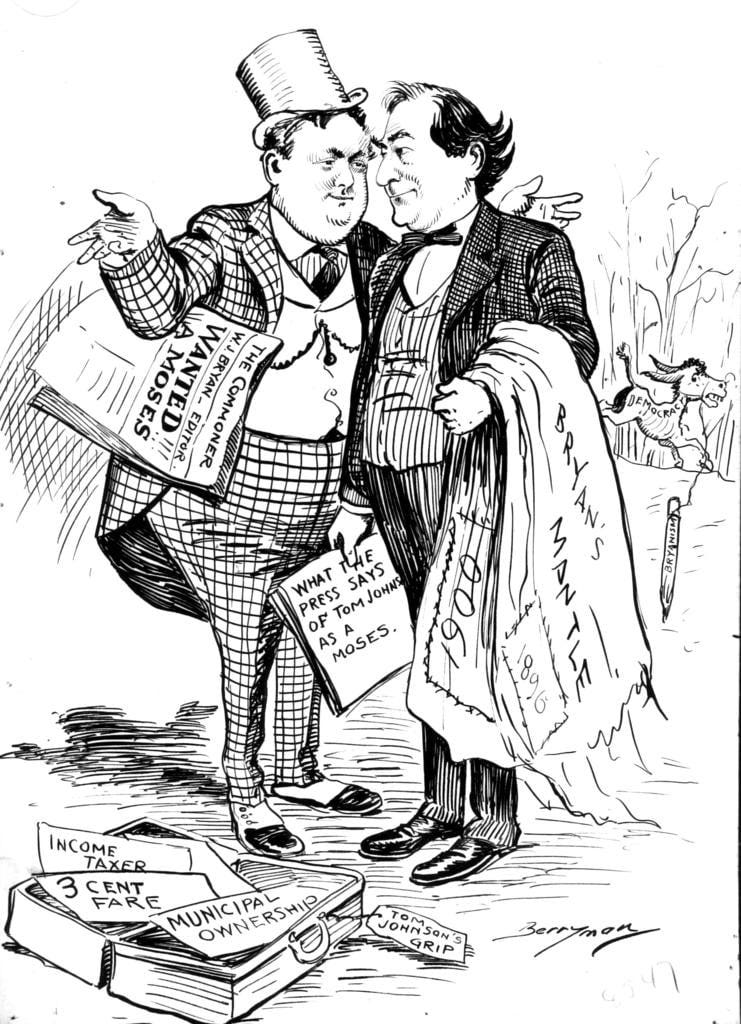

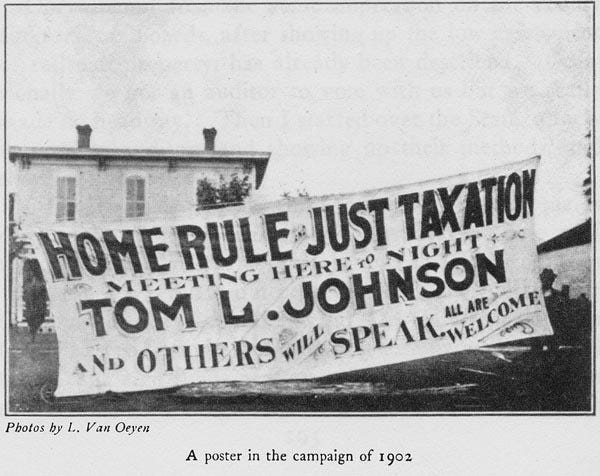

Johnson did not just go on a construction binge though; his efforts were part of a larger anti-monopoly vision. He challenged the privately owned streetcar monopoly with a new streetcar system. The state constitution forbid cities from operating their own businesses, so the streetcar system was run by a private monopoly that negotiated with the city for leases, known as franchises, to use the public streets. Johnson worked to build a new streetcar system with a franchise that required fare to be only 3 cents, rather than 5, and with regulations that would allow the city to purchase it when the state’s constitution was amended. These policies won him the support of suburbanites who relied upon the streetcar system, but also the city’s immigrant working class, which was excited to see a politician for once seemingly serving the average citizen for once.

Paving roads might not seem dramatic enough to turn a mayor a national celebrity but government was so encumbered by layers of judicial scrutiny that it was exceptional to see a politician deliver. While the country had been convulsed with calls for radical economic change for two decades by the time Johnson became mayor, courts reading “freedom of contract” into the constitution ruled against anything that impinged on the prerogatives of business. The Interstate Commerce Act and the Sherman Anti-Trust Act had been effectively voided or even turned on their head by the Supreme Court. The Sherman Anti-Trusts ban on “restraint of trade” was interpreted by the court not to apply to corporations that dominated basic commodities, but to unions that went on strike. Populists and progressives attacked “judge-made law,” injunctions issues by courts that restricted the right of unions to communicate with workers, to organize boycotts, or even provide food to striking workers. In response, some Gilded Age radicals called for reforms that would require a supermajority of judges to overturn acts of the legislature. Theodore Roosevelt suggested judicial recall. Others turned to the popular referendum, which, because it would rewrite a state’s constitution with a simple majority of voters, limited the possibility of judicial interference.

Johnson was not just an expert builder; he was a radical. After reading Henry George’s Progress and Poverty, he devoted his life to the single-tax—a confiscatory tax on land values that would redistribute rent to ensure that everyone had access to a high standard of living. Underlying George’s philosophy was faith that abundance should come naturally: that progress, scientific and social, ought to increase the cornucopia of goods available. This promise remained unfulfilled because certain key goods—notably land—were inherently scarce, and that scarcity meant that they increased in value linearly with economic development. Without redistribution, rent would ensure that the fruits of progress accrued only to those who already owned land, natural resources, or monopolistic businesses like railroads.

For Georgists like Johnson, scarcity was not just a question of poverty, but of power. Georgists would often reference the story of Robison Crusoe, who shipwrecked alone on an island managed to survive by mixing his labor with nature. But what if another shipwreck brought more people to work the land? By cooperating, they should be able to live more comfortably. But, if Crusoe, as the discoverer of the Island, claimed ownership over it, the newcomers would have no option but to work for him under whatever terms he demanded or to launch back into the ocean, likely to their death. The thought experiment illustrated that when access to vital resources is constrained, those who own could them be tantamount to kings. The monopolization of scarce resources was incompatible with republican government.

Everything Johnson accomplished was won against incredible resistance. The city was barred under the state constitution from owning businesses like streetcar lines, and a hostile state government took away much of Johnson’s power over taxation. Courts invalidated the contract for a new streetcar line because it included provisions for the city to purchase the line. Courts issued seventy-seven injunctions that blocked construction of the streetcar system, some on behalf of adjacent property owners, who the radical press claimed were being backed by the streetcar monopoly.

But Johnson’s efforts to cut through this obstructionism with dramatic stunts made him a hero to young progressives. He used the cover of night to defy court injunctions and work on the streetcar system. He hired detectives to follow assessors and prove that they consulted in secret with railroad executives. Johnson turned public meetings into such high drama that his opponents simply skipped out. Newspapers reported: “All you’ve got to do to produce a scatterment in the throne room at the Stark county auditor’s office is to yell ‘Tom Johnson.’”

Johnson’s city clerk, Peter Witt, was an unlikely candidate to become, even for a moment, the “dictator” of a city. An agonistic, he had been a mould maker before his work with the Knights of Labor, a quasi-socialist union, got him blacklisted. Witt became a visceral soapbox orator in Cleveland until one day he confronted a portly ex-streetcar magnate named Tom Johnson at a campaign event. Johnson invited Witt on to stage, explained his own beliefs in socialized monopoly to the craftsman, and then years later tapped him to be the City Clerk. In 1905, when Johnson was traveling, Witt heard news that the town of South Brooklyn was planning to renew its franchise with the streetcar company two days before it was annexed by Cleveland, potentially forcing Cleveland to honor the terms of the monopoly contract that Johnson had campaigned on eliminating. In what came to be known as the “dictatorship of the city clerk,” Witt sent police to the town hall with orders to arrest councilmen if they convened to vote. Other officers were sent to track down the councilmen and intervene if they tried to meet surreptitiously in a private location. The incident ended without further event. However, the story testifies to how important one of the most celebrated urban governments in American history thought it was to cut through process.

These stories made Johnson and his crew a legendary inspiration for a younger generation of progressives that would go on to build the New Deal state. Stuart Chase, who is sometimes credited with coining the term “New Deal” waxed poetic about how “Tom Johnson and the ‘interests’ wrestled naked in the public streets of Cleveland.” Morris Cooke, who would lead the New Deal’s push for rural electrification, recalled that Johnson’s successor, Newton Baker, was stymied in his efforts to build a public power system in Cleveland because manufacturers refused to sell the city the necessary equipment. Cook admiringly observed that Baker “announced that if there were no bids from the responsible manufacturers he would at once take up the matter with Congress by requesting that the tariff duty be thrown off foreign machinery for municipal enterprises. He got his machinery.” Raymond Moley, who assembled FDR’s “Brains Trust,” called Johnson one of the “men behind the New Deal.” Rexford Tugwell called Johnson’s administration “more localized New Deal.”

Today, Social Security cements support for the New Deal and its legacy. But when Tugwell identified the New Deal with Johnson’s administration—which did little in the way of expanding welfare—he highlighted how much importance contemporaries placed on public infrastructure. Franklin Roosevelt, an old money aristocrat who Walter Lippman initially described as “no crusader” or “enemy of entrenched privilege,” did not campaign on radical economic redistribution in 1932, something that was only a focal point for his presidency for a couple years, branded by Jefferson Cowie, “the great exception” to the nation’s generally competitive ethos. The issue with which Roosevelt was most firmly identified with in the public imagination before his presidency was the fight for public waterpower on the St. Lawrence River. As a state senator in 1912, a time when FDR had embraced almost none of the ideas that would constitute the New Deal, he had intoned on the need to expand the “liberty of the community” to protect nature.

Consistent with this focus on environmentally friendly public infrastructure, one of Roosevelt’s first acts in office was to build a public waterpower system in the Muscle Shoals region of the Southeast. The first dams in what would become the TVA had been built by Tom Johnson’s lieutenant, Newton Baker, during World War 1, and Roosevelt had campaigned on keeping these under public ownership. The political impact of public power has receded into the background but in the post-World War II era U.S. officials considered in the top priority for expanding global democracy. Oddete Keun, a Dutch journalist who traveled to the United States looking for solutions to stop the rising tide of authoritarianism, wrote a book on the TVA in which she waxed poetic about “the immortal contribution of the TVA to Liberalism, not only in America, but all over the world, is the blueprint it has drawn, and that it is now transforming into a living reality, of the road which Liberals believe is the only road mankind should travel.” While it was naïve for President Lyndon Johnson to imagine that a hydroelectric dam on the Mekong Delta would undermine support for the Vietcong, his faith reflected his own experience with how expanding access to electricity in West Texas had invigorated confidence in liberal democracy. Johnson’s faith was part of a broader consensus, documented by historian David Ekbladh, that exporting public power projects around the global would erect a powerful bulwark against the expansion of authoritarian regimes.

The New Deal united many contradictory policies and philosophies, but one idea tied them together: vigorous, unobstructed government action was imperative to save democracy. When Roosevelt ascended to the presidency in 1932, fascism had already begun to take root in Europe, where leaders argued that liberal democracies had proven too cumbersome to keep up with the times. In his inaugural address, F.D.R. failed to lay out a unified vision of change. He called simply for experimentation, noting that “this Nation asks for action, and action now.” He even insisted that the sort of vigorous action necessary was permitted under the Constitution but also that “unprecedented demand and need for undelayed action may call for temporary departure from that normal balance of public procedure.”

Historians like Thomas McCraw and Reul Schiller have identified James Landis’s 1938 The Administrative State as the premier statement of the New Deal judicial philosophy of bureaucratic deference. According to Landis, the administrative state dealt with issues too complex for judges, whose background was in law, to deliberate on. Landis wrote that “A world that… could listen to Wordsworth’s denunciation of railroads because their building despoiled the beauty of his northern landscapes is different, very different, from one that in 1938 has to determine lanes and flight levels for air traffic.” These were questions that should be settled by experts, who devoted their lives to the study of these issues. Those experts should be guided by legislatures, whose compromises ensured that laws represented a balanced set of interests, approximating the interest of the public at large. In contrast, courts dealt with clients whose standing was rooted in their ownership of property, and the wealth to employ counsel.

Though the New Deal state had navigated the American republic around some of the most treacherous shoals it had ever traversed, fears of powerful governments like those of the Nazis and Soviets, would spike after the World War II. In 1964, Charles Reich published “The New Property,” in which he argued that government benefits, contracts, and licenses were becoming too important to be left at the discretion of bureaucrats. The power to withdraw government contracts and public resources was potentially the power to destroy. He warned that “if the individual is to survive in the collective society, he must have protections against his ruthless pressures.” Reich would become synonyms with the counterculture and the New Left, especially after the publication of his 1970 book, the Greening of America. But Reich’s New Left was animated by classically liberal individualism and hostility to the state. The counterculture that Reich branded “Consciousness III” was in direct conflict with “Consciousness II,” the bureaucratic, corporate New Deal state. Reich called for a change not through “the political system” with through the “individual… with culture.” Tattered jeans and organic foods that eventually became consumer goods marketed by libertarian businesses like Whole Foods would, in Reich’s book, tear down the collectivist New Deal state and build a more individualistic society.

Reich would inspire a string of Yale graduates to pursue careers in “public interest” law, that the historian Paul Sabin has argued blunted the effective New Deal state and erected a litigious individualism where it had stood. In 1970, the Santa Barbara the ACLU sued to protect: “fundamental right to retain and enjoy the esthetic beauty of natural resources reasonably free of obstruction and pollution.” The New York Times praised the courts for going “beyond property,” but this was exactly the sort of expanded definition of property rights New Dealers like Landis had argued against. If every property owner near the projects of the TVA were able to sue to protect their views, Muscle Shoals might still go dark when the sun set.

Whatever criticisms progressives might have of the people behind the Abundance Agenda, they should be eager to ally with anyone willing to abolish this “New Property.” Tom Johnson believed that because the value of land grew with the development of the community, that value belonged to the public. Public interest law identified the connection between land and community, but--inspired by a bourgeois, middle-class consumerist liberalism--argued the opposite: individuals own the community created values of their land, so they have a legal right to dictate to the community in defense of their socially created property values. Property rights should not supersede democracy; there is no principle more central to the nation’s tradition of reform than that. In a moment when authoritarianism again looms over the world, democratic governments need to demonstrate their ability to act decisively on behalf of voters.

This guest post was written by Christopher England.

In 2023, Christopher England published his first book Land and Liberty: Henry George and the Crafting of Modern Liberalism, the history of a social movement that sought to alleviate inequality by redistributing urban rents. His research has been featured in American Experience, De Correspondent, The New Books Network, The New Liberal Podcast, The Gilded Age and Progressive Era, KZSU Stanford, Civic Story and The New York Times.

He has taught at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Stanford University and Georgetown University. He has also worked in public history as a curator at the Wisconsin Historical Society. He joined Towson University’s history department in 2023. He is currently researching a second book on Social Darwinism and U.S. education.

As a long time Clevelander I am always happy to see articles about Mayor Tom Johnson. You'll notice that the statue of Johnson that sits in Cleveland's Public Square is holding a book. If you actually come and see the statue you will see that the book is Progress and Poverty.

In the future you might want to write more about Rex Tugwell and Green Belt project. Tugwell was a student of Scott Nearing, spent time as a child at the Chautauqua Institution, and was influenced by George. If you've never been to Greenbelt Maryland, they have a great museum and it's worth the trip.

Also you might be interested in Toledo's progressive mayor "Golden Rule" Jones.

There are some unfortunate things going on with commas in this article. I'm a Georgist and would gladly do free editing for this blog.